INTRODUCTION

Lying at the intersection of a number of disciplines, including biology, philosophy, sociology, medicine, anthropology, and artificial intelligence (AI), psychology has always fascinated people. How do psychologists interpret human behaviour to understand why we do what we do? Why are there so many branches and approaches, and how do they work in a practical sense in our day-to-day lives? Is psychology an art or a science, or a fusion of both?

While theories come and go out of fashion, and new studies, experiments, and research are conducted all the time, the essence of psychology is to explain the behaviour of individuals based on the workings of the mind. In these often turbulent and uncertain times, people are increasingly looking to psychology and psychologists to help them make sense of why the powerful and influential behave the way that they do, and the resulting impact that might have on us. But psychology also has huge relevance to those much closer to us than politicians, business magnates, or celebrities – it tells us a great deal about our own families, friends, partners, and other associates. It also resonates a great deal in understanding our own minds, leading to a greater self-awareness of our own thoughts and behaviours.

As well as offering us a basic understanding of all the various theories, disorders, and therapies that form part of this ever-changing field of study, psychology plays a huge role in our everyday lives. Whether it is in education, the workplace, sport, or our personal and intimate relationships – and even the way that we spend our money or how we vote – there is a branch of psychology that impacts on every single one of us in our daily lives on a constant and continued basis.

‘Applied Psychology’ will consider all aspects of psychology – from theories to therapies, personal issues to practical applications, all of which I hope is presented in an accessible and simple way.

WHAT IS PSYCHOLOGY?

The development of psychology – Most advances in psychology are recent, dating back about 150 years, but its origins lie with the philosophers of ancient Greece and Persia. Many approaches and fields of study have been developed, which give psychologists a toolkit to apply to the real world. As society has changed, new applications have also arisen to meet people’s needs.

Psychoanalytical theory

This psychological theory proposes that the unconscious struggles of the mind determine how personality develops and dictates behaviour.

What is it?

Founded by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud in the early 20th century, psychoanalytic theory proposed that personality and behaviour are the outcome of continual conflicts in the mind. The individual is not usually aware of the discord because it takes place at a subconscious level. Freud suggested conflict occurs between three parts of the mind: the id, superego, and ego.

Freud believed that personality develops from birth in five stages, which he called psychosexual because they involve both sexuality and mental processes. At each stage a person’s mind focuses on a different aspect of sexuality, such as oral pleasure when they suck their thumb as a baby. Freud believed that the psychosexual stages trigger a battle between biology and social expectations, and the mind must resolve this conflict before a person can move on to healthy mental development.

Evaluation

Although Freud’s model has been hugely influential in highlighting the role of the subconscious, it has proved controversial because it focuses on sexuality as the driver of personality. Many critics view his model as too subjective, and too simplistic to explain the complex nature of the mind and behaviour.

✔ DEFENCE MECHANISM

. What is it? – Freud argued that people subconsciously employ defence mechanisms when faced with anxiety or unpleasant emotions. These mechanisms help them to cope with memories or impulses that they find stressful or distasteful by tricking them into thinking that everything is fine.

. What happens? – The ego uses defence mechanisms to help people reach a mental compromise when dealing with things that cause internal conflict. Common mechanisms that distort a sense of reality include denial, displacement, repression, regression, intellectualisation, and projection.

. How does it work? – Denial is a common defence mechanism used to justify a habit an individual feels bad about, such as smoking. By saying that they are only a “social smoker”, they can allow themselves to have a cigarette while not admitting that they are in fact addicted to smoking them.

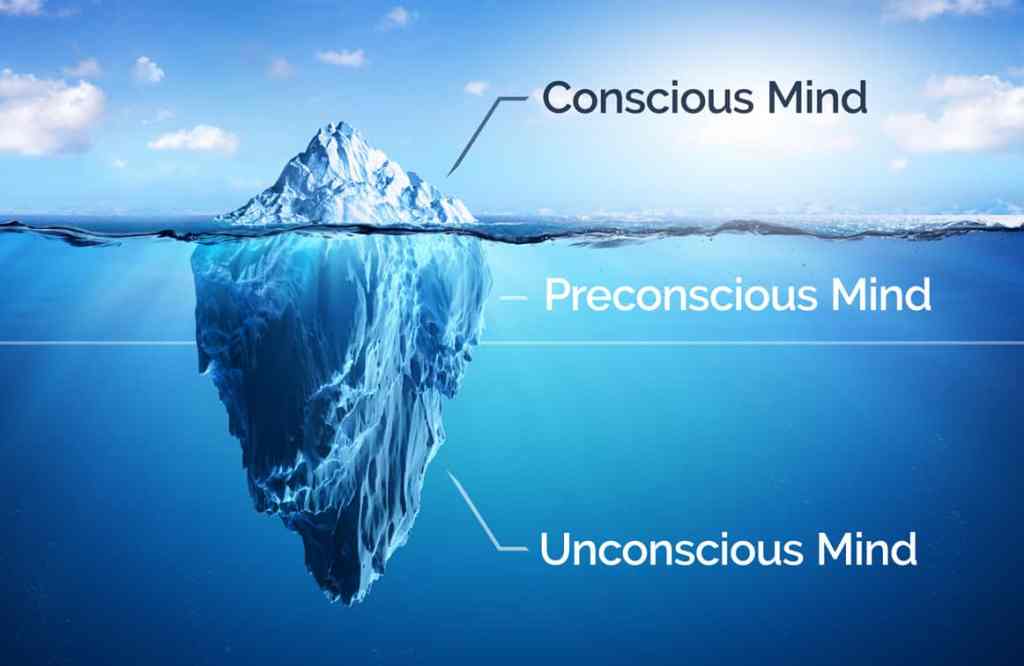

Topographical model

Freud divided the mind into three levels of consciousness. The conscious mind forms only a small part of the whole. Although it is completely unaware of the thoughts in the unconscious mind, the latter still affect behaviour.

[1] Unconscious mind – This hides most of a person’s impulses, desires, and thoughts.

[2] Preconscious mind – This stores information such as childhood memories, which can be accessed through psychoanalysis.

[3] Conscious mind – This contains the ideas and emotions that people are aware of.

Psychoanalysis – In this therapy, the client or patient tells the analyst about their childhood memories and dreams in order to unlock the unconscious mind. This will reveal how it is controlling or triggering undesirable behaviour.

Dreams – Dreams are seen as a channel for unconscious thoughts that people cannot usually access because many of them are too disturbing for the conscious mind to cope with.

Structural model

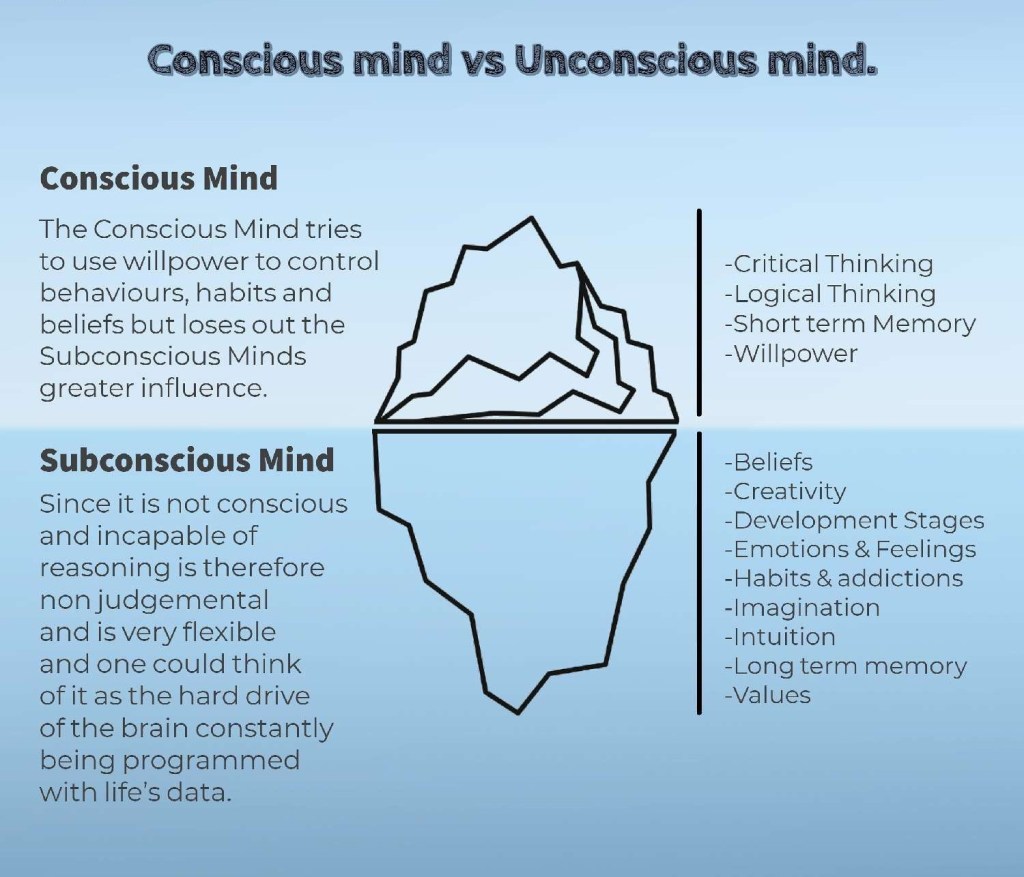

The conscious mind is just the tip of the iceberg, a small part of the hidden whole. Psychoanalytical theory is based on the concept that the unconscious mind is structured in three parts – the id, ego, and superego, which “talk” to one another to try to resolve conflicting emotions and impulses.

The unconscious (or subconscious) mind is broken down further into three components:

ID – This strives for instant gratification, is childlike, impulsive, and hard to reason with.

Ego – This is the voice of reason, negotiating with the id and the superego.

Superego – This wants to do the right thing. It is the moral conscience that takes on the role of a strict parent.

✔ NEED TO KNOW

. Inferiority complex When self-esteem is so low that a person cannot function normally. The idea was developed by neo-Freudian Alfred Adler.

. Pleasure principle What drives the id – the desire to obtain pleasure and avoid pain.

. Neo-Freudians Theorists who built on Freud’s psychanalytic theories, such as Carl Jung, Erik Erikson, and Alfred Adler.

Psychoanalytical histology

1900 Sigmund Freud introduces his theory of psychoanalysis in The Interpretation of Dreams

1909 onwards Developmental psychology emerges prompted by Freud’s emphasis on the importance of childhood experiences

1913 Carl Jung breaks away from his colleague Freud and develops his own theories of the unconscious mind

Behaviourist approach

Behavioural psychology analyses and treats people on the basis that their behaviour is learnt by interacting with the world and that the influence of the subconscious is irrelevant.

What is it?

The starting point for behavioural psychology is a focus on only observable human behaviour, leaving out thought and emotion. This approach rests on three main assumptions. First, people learn their behaviour from the world around them, and not from innate or inherited factors. Second, because psychology is a science, measurable data from controlled experiments and observation should support its theories. Third, all behaviour is the result of a stimulus that triggers a particular response. Once the behavioural psychologist has identified a person’s stimulus-response association, they can predict it, a method known as classical conditioning. In therapy, the therapist uses this prediction to help the client or patient change their behaviour.

Evaluation

The strength of the behaviourist approach – that it can be scientifically proven, unlike Freud’s psychoanalytic approach, for example – has also been seen as its weakness. Many of the behavioural experiments were carried out on rats and dogs, and humanists in particular rejected the assumption that people in the world acted in the same way as animals in laboratory conditions.

Behavioural psychology also takes little account of free will or biological factors such as testosterone and other hormones, reducing human experience to a set of conditioned behaviours.

✔ OPERANT CONDITIONING

This method for inducing behaviour change, in this case training a dog, involves positive or negative actions on the part of the owner to reinforce or punish the dog’s behaviour.

. Positive reinforcement Giving a reward encourages good behaviour. For example, the dog receives a treat for sitting on command. It quickly learns that repeating that behaviour will earn it another treat.

. Negative reinforcement The owner removes something bad to encourage good behaviour. The lead goes slack when the dog walks close to its owner. The dog learns to walk to heel without pulling and so avoid the choking sensation.

. Positive punishment The owner does something unpleasant to discourage bad behaviour. When the dog pulls ahead on the lead, its collar feels uncomfortably tight around its throat.

. Negative punishment Taking away something that the dog enjoys is used to discourage undesired behaviours. For example, the owner turns their back on the dog to deprive it of attention if it jumps up. The dog learns not to jump up.

Themes of behaviourism

John Watson developed behavioural psychology in 1913. His theory chimed with the early 20th-century trend for data-backed science rather than concentrating on the subjective workings of the mind, and the behaviourist approach was influential for decades. Later psychologists interpreted behavioural theory along more flexible lines, but objective evidence remains a cornerstone of research.

Classical conditioning – Pavlov noted that his dogs salivated at the sight of food and started ringing a bell at the same time as feeding them. Soon, the dogs salivated merely at the sound of the bell, which they now associated with food.

Methodological behaviourism – Watson’s theory became known as methodological behaviourism because of its focus on scientific methods:

. He viewed psychology as a science, its goals being the prediction and control of behaviour.

. It is the most extreme theory of behaviourism because it rules out any influence from a person’s DNA or internal mental state.

. It assumes that when people are born, their minds are a blank slate, and they learn all their behaviour from the people and things around them (classical conditioning, above). For example, a baby smiles back when its mother smiles; or cries if its mother raises her voice.

Radical behaviourism – In the 1930s B.F. Skinner developed radical behaviourism, which allowed for the influence of biology on behaviour:

. Like Watson, Skinner believed that the most valid approach to psychology was one based on scientifically observing human behaviour and its triggers.

. Skinner took classical conditioning a step forward with the idea of reinforcement – behaviour that is reinforced by a reward is more likely to be repeated (operant conditioning, above).

Psychological behaviourism – Conceived by Arthur W. Staats, psychological behaviourism gained dominance over four decades. It informs current practice in psychology, especially in education:

. A person’s personality is shaped by learned behaviours, genetics, their emotional state, how their brain processes information, and the world around them.

. Staats researched the importance of parenting in child development.

. He showed that early linguistic and cognitive training resulted in advanced language development and higher performance in intelligence tests when children were older.

Behavioural histology

1913 John B. Watson publishes Psychology as the Behaviourist Views It, outlining the principles of behaviourism

1916 Lewis Terman applies psychology to law enforcement, heralding the beginnings of forensic psychology

1920 Jean Piaget publishes The Child’s Conception of the World, prompting the study of cognition in children

1920s onwards The use of psychometric tests to measure intelligence starts individual differences psychology (self-identity)

1920s Dr Carl Diem founds a sports psychology laboratory in Berlin

1920s Behavioural psychologist John B. Watson begins working in the advertising industry and develops the discipline of consumer psychology

Early 1930s Social psychologist Marie Jahoda publishes the first study of community psychology

Humanism

Unlike other psychological approaches, humanism places central importance on the individual’s viewpoint, encouraging the question, “How do I see myself?” rather than, “How do others see me?”.

What is it?

Whereas behavioural psychology is concerned with observing external actions and psychoanalytical theory delves into the subconscious, humanism is holistic, focusing on how a person perceives their own behaviour and interprets events. It centres on a person’s subjective view of themselves and who they would like to be, rather than the objective view of an observer.

Pioneered by Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow in the 1950s, humanism offers an alternative way of trying to fathom human nature. It assumes that personal growth and fulfilment are primary goals in life, and that emotional and mental wellbeing comes from achieving this. The principle of free will, exercised in the choices a person makes, is also key.

Evaluation

Rogers and other humanist psychologists suggested a number of new methods of investigation, such as open-ended questionnaires in which there were no “right” answers, casual interviews, and the use of diaries to record feelings and thoughts. They reasoned that the only way to really get to know someone was to talk to them.

Humanism is the theory that underpins person-centred therapy – one of the most common therapies for depression. The humanistic approach is also used in education to encourage children to exercise free will and make choices for themselves, and in researching and understanding motivation.

However, humanism ignores other aspects of the individual such as their biology, the subconscious mind, and the powerful influence of hormones. Critics also say that the approach is unscientific because its goal of self-realisation cannot be accurately measured.

GESTALT PSYCHOLOGY

Influenced by humanism, gestalt psychology examines in detail how the mind takes small pieces of information and builds them into a meaningful whole. It emphasises the importance of perception – the laws that govern how each person perceives the world.

Part of gestalt assessment involves showing clients or patients a series of images to discover how they perceive each one. The Rubin Vase illusion is the best known of these and illustrates the law of “figure” and “ground”: a person’s mind always works to distinguish a figure (words, for example) from its background (a white page), and in doing so, decides about priority and what to focus on.

Road to fulfilment

Carl Rogers identified three parts to personality that determine a person’s psychological state: self-worth, self-image, and the ideal self. When a person’s feelings, behaviour, and experience match their self-image and reflect who they would like to be (ideal self), they are content. But if there is a mismatch (incongruence) between these aspects, they are dissatisfied.

INDIVIDUAL OR GROUP?

Humanism is rooted in Western ideas of personal identity and achievement, sometimes called individualism. In contrast, collectivism subordinates the person to the group.

Individualism

. Identity defined in terms of personal attributes – such as outgoing, kind, or generous.

. Own goals take priority over those of the group.

Collectivism

. Identity defined by which group someone belongs to.

. Family, then workplace, are most important groups.

. Goals of group take priority over the individual.

Incongruent – If there is little overlap between how a person sees themselves (self-image) and what they would like to be (ideal self), they feel unhappy, with low self-worth.

Increasingly congruent –With more common ground between self-image and ideal self, a person has greater self-worth and adopts a more positive frame of mind.

Self-actualisation – When a person’s perception of who they are aligns with who they want to be, they achieve self-actualisation. This satisfies their need to reach and express their full potential.

Cognitive psychology

A branch of psychology that considers the mind to be like a complex computer, the cognitive approach analyses the way people process information and how that dictates their behaviour and emotions.

What is it?

When the computer arrived in offices in the late 1950s, it sparked comparisons between artificial information processing and the operation of the human mind. Psychologists reasoned that in the same way that a computer accepts data, codes it for storage, and retrieves it, the human mind takes in information, changes it to make sense of it, stores it, and recalls it when needed. The computer analogy came to be the foundation for cognitive psychology.

The theories behind cognitive psychology can apply to virtually every aspect of daily life. Examples include the brain receiving and processing sensory information to make a judgment (such as recognising that a carton of milk has soured from its bad smell); reasoning with logic to make a decision (such as whether to buy an expensive shirt which may last longer than a cheap one); or learning how to play a musical instrument, which requires the brain to make new connections and store new memories.

Evaluation

Although cognitive psychology emphasises internal processes, it aims to be strictly scientific, relying on laboratory experiments to back up any theory. What happens in controlled experiments, however, can be difficult to apply to real-life scenarios. Similarly, the assumption that the human mind functions like a computer does not consider realities such as people getting tired or emotional, and critics claim it treats humans as machines, reducing all behaviour to a cognitive process such as committing things to memory. Critics have also pointed out that this approach ignores the role of biology and genetics.

However, cognitive psychology has proved useful for treating memory loss and selective attention disorders. It is also valuable in understanding child development, allowing educators to plan appropriate content for each age group, and decide the best tools for delivering it. In the legal system, cognitive psychologists are regularly called on to assess eyewitness reports in order to determine whether a witness has accurately recalled a crime.

Information processing

Using evidence from controlled experiments, psychologists have built theoretical models of how the mind deals with information. According to these models, the human brain handles information in the same sequence a computer uses to handle data – from input, through transformation of the data, to retrieval.

[1] INPUT (from environment) – A person’s sense organs detect stimuli from the external world and send messages to the brain as electrical impulses containing information. For example, if a person’s car breaks down, their brain focuses on warning signs, such as unexpected sounds from the engine, visual clues like smoke, or the smell of burning rubber.

[2] PROCESSING (mediational event) – After receiving information via the senses, the brain must sort through it to analyse it and decide what to do with it. Cognitive psychologists call this process mediational because it happens between (“mediates”) the environmental stimulus and the brain’s eventual response to that stimulus. In the case of the car breakdown, the brain might analyse the smell of burning rubber, and connect with an earlier memory of a similar smell.

[3] OUTPUT (behaviour and emotion) – When the brain has retrieved enough information, it can decide about what response to make, either in the form of a behavioural or an emotional reaction. In the example of the car, the brain recalls memories of previous breakdowns, together with any relevant mechanical information stored, then runs through a mental checklist of possible causes and solutions. It remembers that the smell of burning rubber previously indicated a broken fan belt. The person pulls over, turns off the ignition, and opens the bonnet to check.

“Disconnected facts in the mind are like unlinked pages on the Web: they might as well not exist.” – Steven Pinker, Canadian cognitive psychologist

✔ COGNITIVE BIAS

When the mind makes an error in the course of thought processing it results in a skewed judgment or reaction, known as a cognitive bias. This may be related to memory (poor recall, for example) or lack of attention, usually because the brain is making a mental shortcut under pressure. Biases are not always bad – some are the natural outcome of having to make a quick decision for survival purposes.

Examples of bias

. Anchoring Placing too much importance on the first piece of information heard.

. Base-rate fallacy Abandoning original assumptions in favour of a new piece of information.

. Bandwagon effect Overriding own beliefs in order to go along with what other people are thinking or doing.

. Gamblers’ fallacy Mistakenly believing that if something is happening more often now, it will happen less often in the future – for example, if the roulette wheel consistently falls on black, thinking it is bound to fall on red before long.

. Hyperbolic discounting Choosing a similar reward now, rather than patiently waiting for a larger reward.

. Neglect of probability Disregarding true probability, for example, avoiding air travel for fear of a plane crash, but fearlessly driving a car even though it is statistically far more dangerous.

. Status quo bias Making choices to keep a situation the same, or alter it as little as possible, rather than risk change.

Biological psychology

Based on the premise that physical factors, such as genes, determine behaviour, this approach can explain how twins brought up separately exhibit parallel behaviour.

What is it?

Biological psychology assumes that people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviour all derive from their biology, which includes genetics as well as the chemical and electrical impulses that wire the brain to the nervous system. This assumption implies that the blueprint laid down in the womb – people’s physiological structure and DNA – dictates their personality and behaviour as they go through life.

Some of these ideas are based on the results of twin studies, which have shown that twins separated at birth and brought up in different households display remarkably similar behaviour in adult life. Biopsychologists argue that this phenomenon can only be explained if the twins’ genetics influence them so strongly that not even the role of their parents, friends, life experiences, or environment have much impact.

An example of biological psychology in action is the research into how teenagers behave. Scans of teenage brains using imaging technology have revealed that adolescent brains process information in a different way to adult brains. These differences help to offer a biological explanation for why teenagers can be impulsive, sometimes lack good judgement, and become overly anxious in social situations.

Evaluation

Many of the ideas in biological psychology emphasise nature over nurture. As a result, critics consider the approach to be oversimplistic, giving undue weight to the influence of biology and inbuilt physical attributes. Little credit is given to the influence of events or people on an individual as they grow up. On the other hand, few argue with the rigorous scientific backbone of the approach, which places importance on the systematic testing and validation of ideas. And biopsychologists have enabled important medical advances – using research from neurosurgery and brain imaging scans they have made positive contributions to treatment for patients with both physical and mental problems, including Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, depression, and drug abuse.

EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY

Psychologists in this field explore why people’s behaviour and personality develop differently. They investigate how individuals adapt their language, memory, consciousness, and other complex biological systems to cope best with the environment they find themselves in. Key ideas include:

. Natural Selection This has its origins in Charles Darwin’s hypothesis that species adapt over time or evolve mechanisms that facilitate survival.

. Psychological adaptations This looks at mechanisms people use for language acquisition, for differentiating kin from non-kin, for detecting cheats, and for choosing a mate based on certain sexual or intelligence criteria.

. Individual differences This seeks to explain the differences between people – for example, why some people are more materially successful than others.

. Information processing This evolutionary view suggests that brain function and behaviour have been moulded by information taken in from the external environment, and so are the product of repeatedly occurring pressures or situations.

Different approaches

Biopsychologists are interested in how the body and biological processes shape behaviour. Some focus on the broad issue of how physiology explains behaviour, while others concentrate on specific areas such as the medical applications of the theory or experiments to determine whether an individual’s genetics dictate their behaviour.

Physiological – This approach assumes that biology shapes behaviour. It seeks to discover where certain types of behaviour originate in the brain, how hormones and the nervous system operate, and why changes in these systems can alter behaviour.

Medical – This branch explains and treats mental disorders in terms of physical illness. Disorders are considered to have a biological basis, such as a chemical imbalance in the body or damage to the brain, rather than causes linked to environmental factors.

Genetics – This field attempts to explain behaviour in terms of patterns that are laid down in each person’s DNA. Studies of twins (especially twins separated at birth and raised in different homes) have been used to show that traits such as IQ are inherited.

“In the last analysis the entire field of psychology may reduce to biological electrochemistry.” – Sigmund Freud, Austrian neurologist

How the brain works

Studies of the brain have given valuable insight into the vital correlation between brain activity and human behaviour, as well as revealing the complex process by which the brain itself is brought to life.

Connecting brain and behaviour

Understanding the biology of the brain and how it works became vital with the rise of neuroscience in the 20th century. Studies in this field confirmed that the brain itself is fundamentally intertwined with human behaviour, and prompted the emergence of specialist fields, such as neuropsychology. This relatively new branch of science combines cognitive psychology (the study of behaviour and mental processes) with brain physiology and examines how specific psychological processes relate to the brain’s physical structure. Investigating the brain in this light raises the age-old question of whether mind and body can be separated.

The relationship between brain and mind has been debated since the time of Ancient Greece and Aristotle, when prevailing philosophical thought labelled the two entities as distinct. This theory, which Réne Descartes reiterated in the 17th century with his contempt of dualism, permeated studies of the brain until well into the 20th century.

Modern neurological research and advances in technology have enabled scientists to trace certain behaviours to specific areas of the brain, and to study connections between the different regions. This has radically advanced knowledge of the brain and its effect on behaviour, mental function, and disease.

SPECIALISATION OF THE CEREBRAL HEMISPHERES

Cerebral cortex – Nerve fibres cross over at the base the brain, so each hemisphere controls the opposite side of the body.

Left hemisphere

. This controls and coordinates the right side of the body.

. It is the analytical side of the brain.

. It is responsible for tasks relating to logic, reasoning, decision-making, and speech and language.

Right hemisphere

. This controls muscles on the left side of the body.

. It is the creative side of the brain.

. It deals with sensory inputs, such as visual and auditory awareness, creative and artistic abilities, and spatial perception.

Mind controlling brain Dualism argues that the non-physical mind and the physical brain exist as separate entities but are able to interact. It considers that the mind controls the physical brain but allows that the brain can at times influence the normally rational mind, for example, in a moment of rashness or passion.

Brain controlling mind

Monoism recognises every living thing as material, and that the “mind” is therefore purely a function of the physical brain. All mental processes, even thoughts and emotions, correlate to precise physical processes in the brain. Cases of brain damage reinforce this: minds alter when the physical brain is altered.

Mind-body dualism

Humans are innately reluctant to reduce consciousness to pure biology. But the scientific evidence shows that the physical firing of neurons generates our thoughts. Two schools of thought, monoism and dualism, dominate the question of whether the mind is part of the body, or the body part of the mind.

Brain studies

Linking behaviour to a specific area of the brain first began with 19th century-studies of people with brain damage, as changes in behaviour could be correlated directly to the site of injury. In one case, a worker survived injury to his frontal lobe and the ensuing changes in his character suggested the formation of personality occurs in that area of the brain. The two linguistic functions of Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas were named after the surgeons who dissected the brains of two patients who had linguistic problems when alive. Each brain showed malformations in a specific area, indicating where spoken language is generated (Broca’s area) and understood (Wernicke’s area). However, evidence of interconnections between regions suggest certain functions may be linked to more than one area. Roger Sperry’s work in the 1960s on the cerebral hemispheres was a landmark in brain research. Studying patients whose hemispheres had been surgically divided, he found each side had specialised cognitive skills. He also realised that each hemisphere could be independently conscious.

However, all brain studies have limitations – they show correlations between brain activity and behaviour, not absolutes. Surgical procedures on or damage to one part of the brain may affect other areas, which could account for observed behavioural changes. Equally, tests on brain-damaged patients offer no experimental control and can only observe behaviour occurring after the damage.

Mapping the brain

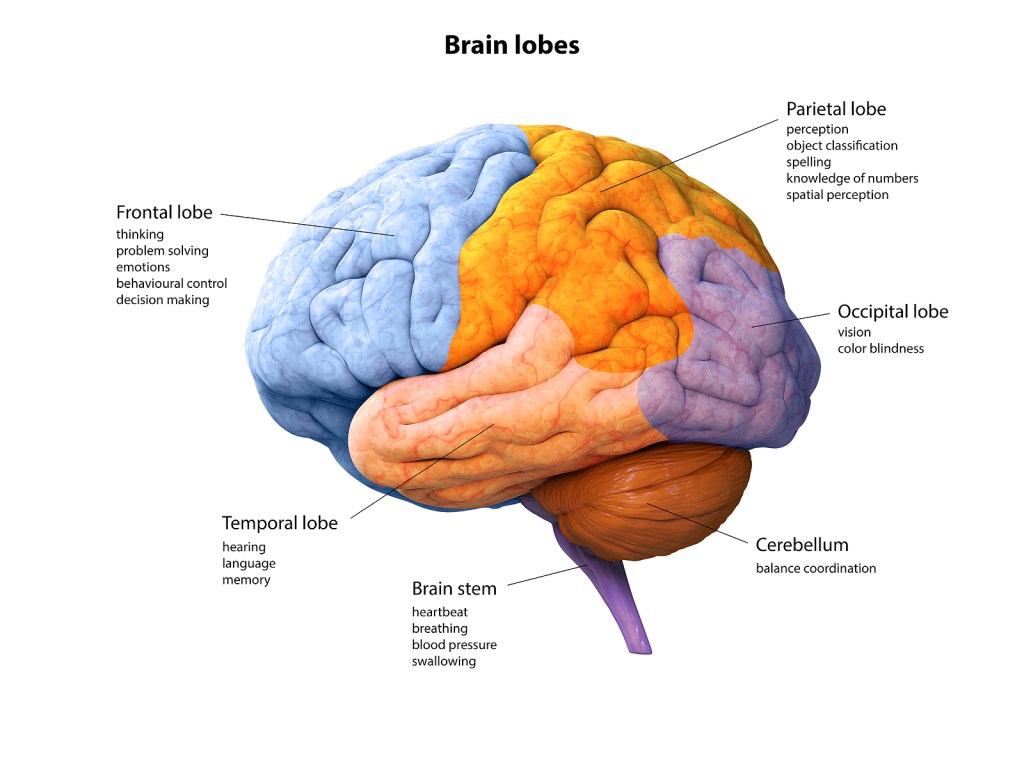

One of the most complex systems in nature, the human brain controls and regulates all our mental processes and behaviours, both conscious and unconscious. It can be mapped according to its different neurological functions, each of which takes place in a specific area.

The hierarchy of mental processing is loosely reflected in the brain’s physical structure: high-level cognitive processes take place in the upper areas, while more basic functions occur lower down. The largest and uppermost region (the cerebral cortex) is responsible for the highest-level cognitive functions, including abstract thought and reasoning. It is the capacity of their cerebral cortex that separates humans from other mammals. The central limbic areas control instinctive and emotional behaviour, while structures lower in the brain stem maintain vital bodily functions, such as breathing.

Functional divisions

The cerebral cortex (also called the cerebrum) divides into two separate but connected hemispheres, left and right. Each one controls a different aspect of cognition. Further divisions include four paired lobes (one pair on either hemisphere), each of which is associated with a specific type of brain function.

The frontal lobe is the seat of high-level cognitive processing and motor performance; the temporal lobe is involved in short- and long-term memories; the occipital lobe is associated with visual processes; and the parietal lobe with sensory skills.

Brain imaging techniques, such as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), measure activity in the different brain areas, yet their value to psychologists can be limited. Those studying fMRI results need to be aware, for example, of the issue of “reverse inference”: just because a particular part of the brain is shown to be active during one cognitive process does not mean it is active because of that process. The active area might simply be monitoring a different area, which is in fact in control of the process.

Locating brain function

Psychologists and neurologists can map neurological function when small areas of the brain are stimulated. Using brain scanning techniques, such as fMRI or CT, they study and record the sensation and movements this stimulation produces.

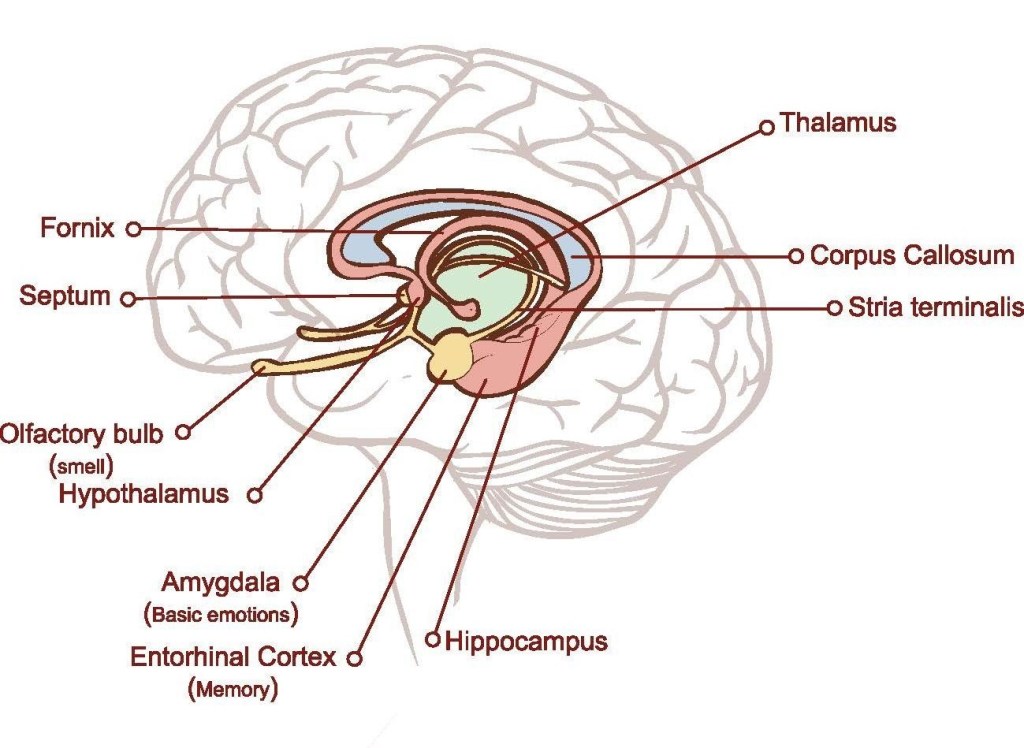

The limbic system

This complex set of structures is involved in processing emotional responses and the formation of memories.

Hypothalamus Involved in regulating body temperature and water levels and key behavioural responses.

Olfactory bulb Relays messages about smell to the central limbic areas for processing.

Amygdala Processes emotions; affects learning and memory.

Thalamus Processes and sends data to higher brain areas.

Hippocampus Converts short-term memories into long-term ones.

BRAIN LOBES

– Notes on brain lobes

. Parietal Lobe incorporates both the motor cortex and the sensory cortex. The motor cortex is the primary area of the cerebral cortex which is involved in motor function. It controls voluntary muscle movements, including planning and execution.

Information gathered by all five senses is processed and interpreted within the sensory cortex. Sensory receptors from around the body send neural signals to this cortex.

. Occipital Lobe is the primary visual cortex. Visual stimuli are initially processed in this cortex, enabling recognition of colour, movement, and shape. It sends signals on to other visual cortices to be processed further.

. Frontal Lobe. Within the frontal lobe the Broca’s area is found. This is the area in the left hemisphere which is vital to the formation of articulated speech.

The frontal lobe comprises a number of cortices. The Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is the area linked to various high-level mental processes including “executive functions” – the processes involved in self-regulation or mental control. The OFC (orbital frontal cortex) is part of the prefrontal cortex, the OFC connects with the sensory and limbic areas; it plays a role in the emotional and reward aspect of decision-making. The frontal lobe also comprises the supplementary motor cortex, one of the secondary motor cortices, which is involved in planning and coordinating complex movements. It sends information to the primary motor cortex.

. Wernicke’s area plays a key role in the comprehension of spoken language.

. Cerebellum is involved in balance and posture; it coordinates sensory input with muscle response.

. Brain stem This is the main control centre for key bodily functions, such as swallowing or breathing.

The tempo-parietal junction is located between the temporal and parietal lobes and is the area which processes signals from the limbic and sensory areas. It has been linked with the comprehension of “self”.

Lighting up the brain

The human brain contains around 86 billion specialised nerve cells (neurons) which “fire” chemical and electrical impulses to allow communication between them and the rest of the body. Neurons are the core building blocks of the brain and connect to form complex pathways through the brain and central nervous system.

Neurons separate at a narrow junction called a synapse. In order to pass a signal on, the neuron must first release biochemical substances, known as neurotransmitters, which fill the synapse and activate the neighbouring cell. This impulse can then flow across the synapse in a process known as synaptic transmission. In this way the brain sends messages to the body to activate the muscles, and the sensory organs are able to send messages to the brain.

Forming pathways

A neuron’s unique structure enables it to communicate with up to 10,000 other nerve cells, creating a complex interconnected neural network that allows information to travel at great speed. Studies of synaptic transmission indicate that pathways within this vast network link to specific mental functions. Every new thought or action creates a new brain connection, which strengthens if it is used repeatedly, and it is then more likely that the cells will communicate along that pathway in the future. The brain has “learned” the neural connections associated with that particular activity or mental function.

Neurotransmitters

Many different types of neurotransmitters are released at a synapse and may have either an “excitatory” or “inhibitory” effect on a target cell. Each type is linked with a specific brain function, such as regulating mood or appetite. Hormones have a similar effect, but they are transmitted by blood, rather than across the synaptic cleft.

Acetylcholine The effects of this neurotransmitter are mostly excitatory and activate the skeletal muscles; it is also linked to memory, learning, and sleep.

Adrenaline Released in stress situations, adrenaline creates an energy surge which increases the heart rate, blood pressure, and blood flow to the larger muscles.

Dopamine With either an inhibitory or excitatory effect, dopamine plays a key role in reward-motivated behaviour and links to mood.

Endorphins Released by the pituitary gland, endorphins have an inhibitory effect on the transmission of pain signals; they are associated with pain relief and feelings of pleasure.

GABA The brain’s main inhibitory neurotransmitter, GABA slows the firing of neurons and is calming.

Glutamate The most common neurotransmitter, glutamate has an excitatory effect and links to memory and learning.

Noradrenaline Similar to adrenaline, this excitatory neurotransmitter is mainly associated with the fight-or-flight mechanism; it is also linked to stress resilience.

Serotonin With an inhibitory effect, serotonin is linked to mood enhancement and calmness. It regulates appetite, temperature, and muscle movement.

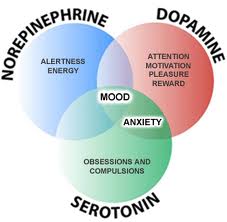

✔ CHEMICAL EFFECTS AND OVERLAPS

These three neurotransmitters have distinct yet interrelated roles:

Serotonin (emotional wellbeing)

Dopamine (fluid muscle motion; rewarding motivation)

Noradrenaline (mobilising body under stress)

. All affect mood.

. Noradrenaline and dopamine are both released in stressful situations.

. Serotonin moderates a neuron’s response to the excitatory effects of dopamine and noradrenaline.

How memory works

Every experience generates a memory – whether it lasts depends on how often it is revisited. Intricate neural connections allow memories to form, and these can strengthen – aiding recall – or fade away.

What is memory?

A memory is formed when a group of neurons fire in a specific pattern in response to a new experience – these neural connections can then re-fire in order to reconstruct that experience as a memory. Memories are categorised into five types. They are briefly stored in the short-term (working) memory but can fade unless the experience is of emotional value or importance, in which case it is encoded in the long-term memory. In recalling a memory, the nerve cells that first encoded it are reactivated. This strengthens their connections and, if done repeatedly, solidifies the memory. A memory’s component parts, such as related sounds or smells, reside in different areas of the brain, and in order to retrieve the memory all of these brain parts must be activated. During a recall a memory can merge accidentally with new information, which fuses irrevocably with the original (known as confabulation).

Endel Tulving explained memory as two distinct processes: storing information in long-term memory; and retrieving it. The link between the two means that being reminded of the circumstances in which a memory was stored can act as a trigger to recall the memory itself.

✔ TYPES OF MEMORY

. Episodic memory Recalling past events or experiences. Closely linked with sensory and emotional intelligence.

. Semantic memory Retaining factual information, such as the name of a capital city.

. Working memory Storing information temporarily; capable of holding between five and seven items at any one time; also known as short-term memory.

. Procedural (body) memory Using learned actions that require no conscious recall, such as riding a bicycle.

. Implicit memory Bringing back an unconscious memory that influences behaviour, such as recoiling from a stranger reminiscent of someone unpleasant.

🔎 CASE STUDY: BADDELEY’S DIVERS

Studies by psychologists indicate that in retrieving memories humans are aided by memory cues. British psychologist Alan Baddeley conducted an experiment in which a group of divers were asked to learn a list of words – they learned some words on dry land and some underwater. When they were later asked to recall the words, most divers found recall easier in the physical environment in which they had first memorised them, so it was easier to remember the words learned underwater when they went underwater. Baddeley’s experiment suggested that context itself could provide a memory cue. Similarly, when a person goes to collect an object from another room but on arriving cannot recall what they were looking for, often returning to the original room triggers that memory cue.

How memories form

The process of laying down (encoding) a memory depends on many factors. Even once encoded a memory can take two years to be firmly established.

[1] Attention (0.2 seconds) – focusing attention on an event helps to solidify the memory: the thalamus activates neurons more intensely, while the frontal lobe inhibits distractions.

[2a] Emotion (0.25 seconds) – High emotion increases attention, making an event more likely to be encoded into a memory. Emotional responses to stimuli are processed in the amygdala.

[2b] Sensation (0.2 to 0.5 seconds) – Sensory stimuli are part of most experiences and if of high intensity they increase the chances of recollection. Sensory cortices transfer signals to the hippocampus.

[3] Working memory (0.5 seconds to 10 minutes) – Short-term memory stores information until needed – it is kept active by two neural circuits that incorporate the sensory cortices and the frontal lobes.

[4] Hippocampal processing (10 minutes to 2 years) – Important information transfers to the hippocampus, where it is encoded. It can then loop back to the brain area that first registered it, to be recalled as a memory.

[5] Consolidation (2 years onwards) – The neural firing patterns that encode an experience carry on looping from the hippocampus to the cortex – this firmly fixes (consolidates) it as a memory.

How emotions work

The emotions an individual feels on a daily basis dictate the type of person they feel they are. And yet it is a series of biological processes in the brain that generate every feeling a person has.

What is emotion?

Emotions impact hugely on people’s lives – they govern their behaviour, give meaning to their existence, and are at the core of what it is considered to be human. Yet in reality emotions result from psychological processes in the brain triggered by different stimuli – the psychological significance read into emotions is an entirely human construct. Emotions evolved to promote human success and survival by initiating certain behaviours: for example, feelings of affection prompt the desire to find a mate, reproduce, and live in a group; fear generates a psychological response to avoid danger (fight-or flight); reading emotions in others makes social bonding possible.

Processing emotion

The limbic system (see above), located just under the cortex, generates all emotions. They are processed via two routes, conscious and unconscious. The primary receptor that “screens” the emotional content of all incoming stimuli is the amygdala, which signals to other areas of the brain to produce an appropriate emotional response. Connections between the limbic system and the cortex, in particular the frontal lobes, enables emotions to be processed consciously and experienced as valuable “feelings”.

Each emotion is activated by a specific pattern of brain activity – hatred, for example, stimulates the amygdala (which is linked to all negative emotion) and areas of the brain associated with disgust, rejection, action, and calculation. Positive emotion works by reducing activity in the amygdala and those cortical regions linked to anxiety.

Conscious and unconscious emotive routes

Humans experience their emotional responses through an unconscious route, which is designed to prepare the body for rapid action (fight-or-flight), or via a conscious route, which enables a more considered response to a situation. The amygdala responds to threat and can detect stimuli before the person is even aware of it, provoking an automatic, unconscious reaction. A simultaneous, but slower, transmission of sensory information to the cortex creates a conscious secondary route for the same stimulus and can modify the initial reaction.

Thalamus All sensory information comes to the thalamus for distribution to the amygdala for quick assessment and action (unconscious), and to the cerebral cortex for slower processing to conscious awareness.

Unconscious flow – Thalamus to:

– Amygdala The amygdala instantly assesses incoming information for emotional content. It sends signals to other areas for immediate bodily action. It operates unconsciously and so is liable to make errors. Then to:

– Hypothalamus Signals from the amygdala come to the hypothalamus, which triggers hormonal changes that make the body ready for “fight or flight” in response to emotional stimuli. The muscles contract and the heart rate increases. Outcome:

– Reflex Facial Expressions The emotional reaction caused by the amygdala sparks spontaneous, uncontrolled facial expressions (feeling-signals-expressions).

Conscious flow – (Slow, accurate route) Thalamus to:

– Sensory cortex All sensory information comes to the sensory cortex for recognition. It extracts more information along this path, but the process takes longer than the unconscious route. Then to:

– Hippocampus Consciously processed information is encoded in the hippocampus to form memories. This hippocampus also feeds back stored information, confirming or modifying the initial response. Outcome:

– Conscious Facial Expressions The motor cortex allows a person to control facial expression and so hide or express genuine emotion (conscious intervention).

EMOTIVE BEHAVIOURS AND RESPONSES

Typical behavioural patterns in response to emotion have evolved in order to neutralise any perceived threat, either through fight or appeasement. In contrast, moods last longer, are less intense, and involve conscious behaviours.

| EMOTION | POSSIBLE STIMULUS | BEHAVIOUR |

| Anger | Challenging behaviour from another person | Provokes unconscious response and rapid emotion; “fight” reaction prompts dominant and threatening stance or action |

| Fear | Threat from stronger or more dominant person | Provokes unconscious response and rapid emotion; “flight” response avoids threat, or a show of appeasement indicates lack of challenge to dominant person |

| Sadness | Loss of loved one | Conscious response dominates; longer-term mood; backward-looking state of mind and passivity avoids additional challenge |

| Disgust | Unwholesome object such as rotting food | Provokes unconscious rapid response; aversion prompts swift removal of self from unhealthy environment |

| Surprise | Novel or unexpected event | Provokes unconscious rapid response; attention focuses on object of surprise to glean maximum information that guides further conscious actions |

This concludes the narrative for the page ‘Applied Psychology (1)’. Amendments to the above entries may be made in the future.