Psychological Disorders

The distressing symptoms of a psychological disorder often go hand in hand with circular thoughts, feelings, and actions. When the symptoms form a recognisable pattern, a medical doctor can diagnose and treat a person.

Diagnosing disorders

The medical diagnosis of a mental health condition is a complex process of matching an individual’s pattern of physical and psychological symptoms to behaviours associated with a disorder, or disorders. Some conditions, such as a learning disability or neuropsychological problems are easily identified. Functional disorders that affect personality and conduct are more difficult, however, as they involve numerous biological, psychological, and social factors.

What are mental health disorders?

Mental health disorders are characterised by the presence of unusual or abnormal mood, thinking, and behaviours that cause an individual significant distress or impairment, and disrupt their ability to function. Impairment occurring as the result of common stressors such as bereavement would not be considered a disorder. Diverse social and cultural factors impacting on behaviours might also rule out the presence of mental health problems.

Disorders can be classified into diagnostic groups (which will be examined on this page) and the two main works used to identify, categorise, and organise them are the World Health Organisation’s International Clarification of Disease (ICD-10) and the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).

Assessment of a mental health condition

Clinical diagnosis is only made after a careful assessment process that includes observation and interpretation of a person’s behaviours and discussion with them and, if relevant, their family, carers, and specialist professionals. Putting a name to a person’s distress can help them – and their support systems – gain a deeper understanding of their difficulties, and manage them better, but it can also negatively shape a person’s outlook and contribute to self-fulfilling prophecies.

✔ Physical examination – A doctor will first eliminate physical illness that could be causing symptoms. Medical examination can also reveal intellectual disabilities or speech disorders due to physical abnormalities. Imaging techniques may be used to test for brain injury or dementia, and blood tests can reveal a genetic predisposition to certain disorders.

✔ Clinical interview – If no physical illness is identified, an individual may be referred to a mental health specialist. They will ask the patient about their life experiences, their family history, and recent experiences that relate to their problem. The conversation will also aim to uncover any predisposing factors, strengths, and vulnerabilities.

✔ Psychological tests – Particular aspects of a person’s knowledge, skill, or personality will be evaluated through a series of tests and/or tasks, usually in the form of checklists or questionnaires standardised for use on very specific groups. For example, such tests may measure adaptive behaviours, beliefs about the self, or traits of personality disorder.

✔ Behavioural assessment – A person’s behaviour will also be observed and measured, normally in the situation where their difficulties occur, to gain an understanding of the factors that precipitate and/or maintain their symptoms. The patient might also be asked to make their own observations by recording events in a diary or using a frequency counter.

Depression

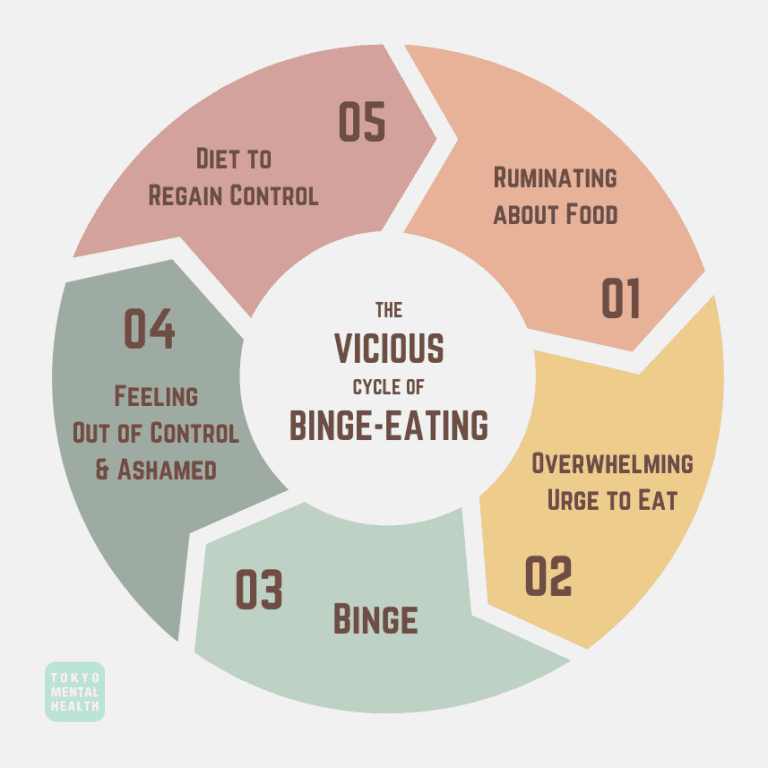

This is a common condition that may be diagnosed when a person has been feeling down and worried, and has lost pleasure in daily activities, for more than two weeks.

What is it?

The symptoms of depression can include continuous low mood or sadness, having low self-esteem, feeling hopeless and helpless, being tearful, feeling guilt-ridden, and being irritable and intolerant of others.

A person with depression is unmotivated and uninterested, finds it difficult to make decisions, and takes no enjoyment from life. As a result, the individual may avoid the social events that they normally enjoy, so missing out on social interaction, which can cause a vicious circle which sees them spiralling further downwards.

Depression can make it difficult for a person to concentrate and remember things. In extreme cases the sense of hopelessness may lead to thoughts of self-harm.

Many internal and external factors such as childhood experiences and life events, physical illness, or injury, can cause depression. It can be mild, moderate, or sever and is extremely common – according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) more than 350 million people suffer from it globally.

How is it diagnosed?

A medical doctor can make a diagnosis by asking the person questions about their particular symptoms. One objective is to find out how long the symptoms have been going on. The doctor may also suggest blood tests to rule out any other illness that may cause the symptoms of depression.

Subsequent treatment depends on the severity of the depression, but the main option is to undergo psychotherapy. Antidepressants may be offered to help the person cope with everyday life. For mild to moderate depression, exercise can be helpful. In severe cases, hospital admission or medication for psychotic symptoms may be needed.

Internal and external causes

A wide range of biological, social, and environmental factors can cause depression. External causes predominately encompass life events that can have a negative impact upon a person, and often act in combination with internal causes – those within an individual – to trigger depression.

. External causes:

Money, or the lack of it, and the stress caused by financial concerns and worries about debt.

Stress when a person cannot cope with the demands on them.

Job or unemployment effects status and self-esteem, perception of a positive future, and ability to engage socially.

Bereavement following the death of a family member, or pet.

Alcohol and drugs due to the physiological, social, and economic consequences of addiction.

Bullying among children and adults, whether physical or verbal, face to face or online.

Loneliness as a result of health or disability, especially in the elderly.

Pregnancy and birth and the overwhelming prospect of parenthood for new mothers.

Relationship problems leading to depression in the longer-term.

. Internal causes:

Personality traits, such as neuroticism and pessimism.

Childhood experiences, especially if the person felt out of control and helpless at the time.

Family history, if a parent or sibling has had depression.

Long-term health problems, such as heart, lung, or kidney disease, diabetes, and asthma.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive and behavioural therapies such as behavioural activation, cognitive behaviour therapy, compassion focused, acceptance and commitment, and cognitive therapies.

. Psychodynamic psychotherapy and counselling.

. Antidepressants on their own or alongside therapy.

Bipolar disorder

This condition is characterised by extreme swings – highs (mania) and lows (depression) – in a person’s energy and activity levels, which is why it was originally called manic depression.

What is it?

There are four types of bipolar disorder: bipolar 1 is severe mania lasting for more than a week (the person may need hospitalisation); bipolar 2 causes swings between a less severe mania and low mood; cyclothymia features longer-term hypomanic and depressive episodes lasting for up to two years; and unspecified bipolar disorder, which is a mixture of the three types. During a mood swing an individual can undergo extreme personality changes, which puts social and personal relationships under severe strain.

The main cause of bipolar is commonly believed to be an imbalance of the chemicals in brain function. Known as neurotransmitters, these chemicals include noradrenaline, serotonin, and dopamine, and relay signals between nerve cells, see: Applied Psychology (1). Genetics also play a role: bipolar disorder runs in families, and it can develop at any age. It is thought that two in every 100 people have an episode at some stage; some only have a couple in their lifetime, while others have many. Episodes may be triggered by stress; illness; or hardships in everyday life, such as relationship difficulties or problems with money or work.

How is it diagnosed?

The affected person is assessed by a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist, who asks about the symptoms and when they first occurred. Signals leading up to an episode are explored too. The doctor also looks to eliminate other conditions that can cause mood swings. The individual is usually treated with medication and lifestyle management techniques.

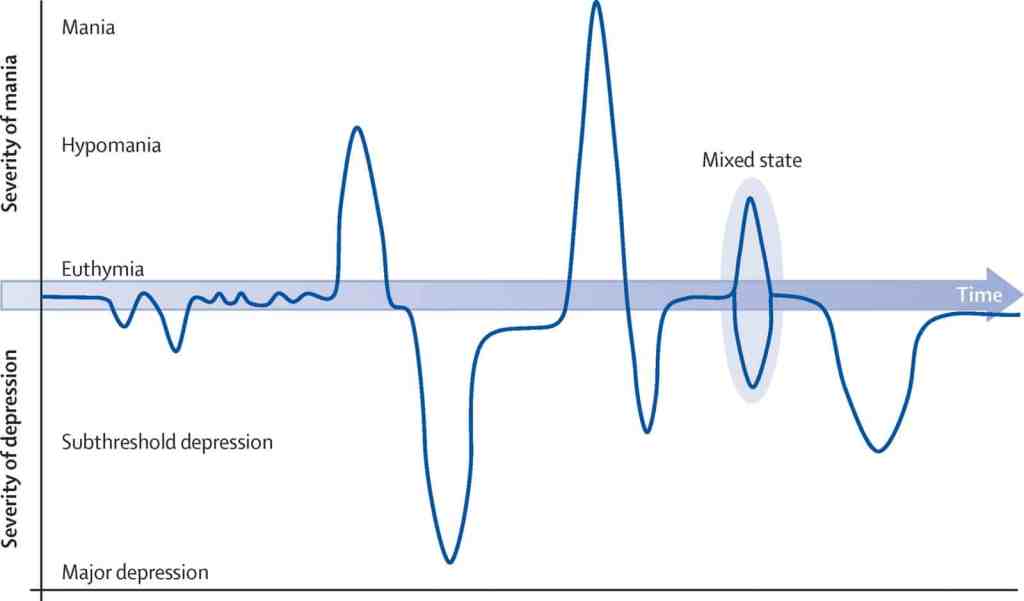

There are distinct phases to the mood swings of bipolar disorder. The extent and timescale of fluctuations and the way moods manifest themselves and affect personality can vary widely.

Balanced/Normal Mood This is a state between episodes in which the person copes with regular daily routines and can plan and predict the consequences of day-to-day actions.

Hypomania In this form of mania, lasting a few days, an individual can be highly productive and function well. It can precede full mania.

Depression The person cannot experience pleasure, has difficulty sleeping, no appetite, may be delusional, hallucinate, and experience disturbed, even suicidal thoughts.

Mania This severe form may last a week or more. Symptoms include hyperactivity, rapid uninterruptable and loud speech, risk-taking, lack of sleep, and inflated self-image.

Mixed State The person suffers from mania at the same time as depression. The individual may, for example, be hyperactive and have depressive symptoms at the same time.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy

. Lifestyle management including regular exercise, better diet, and sleep routines, which may improve mood regulation; and use of diaries and daily awareness methods, which may help the individual to recognise signs of mood changes.

. Mood stabilisers taken long term to minimise likelihood of mood swings; medication dosage often adjusted during episodes of hypomania, mania, or depression.

Perinatal mental illness

Occurring at any time during pregnancy and up to a year after giving birth, perinatal mental illnesses include PPD (postpartum depression), sometimes called postnatal depression, and postpartum psychosis.

What is it?

Feeling tearful or irritable just after giving birth is so common it is dubbed the “baby blues”, but these feelings only last for a couple of weeks. What sets PPD apart from baby blues is the length of time it lasts. It is a longer-term moderate to severe depression that can develop in new mothers (and occasionally fathers) at any time in the year after birth. Symptoms include constant low mood or mood swings, low energy levels, difficulty bonding with the baby, and frightening thoughts. The individual may cry easily and profusely and feel acutely fatigued yet have sleep problems. Feelings of shame and inadequacy, worthlessness, and fear of failure as a parent are common. In severe cases, panic attacks, self-harm, and thoughts of suicide occur. However, most individuals make a full recovery. Untreated, PPD may last for many months or longer.

PPD can develop suddenly or slowly and is usually caused by hormone and lifestyle changes and fatigue. It is not clear why some people develop PPD, but risk factors appear to include difficult childhood experiences, low self-esteem, a lack of support, and stressful living conditions.

How is it diagnosed?

To determine whether an individual has PPD, a doctor, midwife, or health visitor assesses symptoms using an efficient and reliable screening questionnaire such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, which rates mood and activity levels over the previous seven days. Other assessment scales are used to assess mental wellbeing and functioning.

Good clinical judgement is needed when interpreting the results of these questionnaires as new parents are likely to be less active simply as a result of their new responsibilities.

POSTPARTUM PSYCHOSIS

An extremely serious condition, postpartum psychosis (also known as puerperal psychosis) affects 1–2 women per 1,000 births. It usually occurs in the first few weeks after delivery but may begin up to six months after birth. Symptoms often develop rapidly and include confusion, high mood, racing thoughts, disorientation, paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, and sleep disturbance. The individual may also have obsessive thoughts about the baby. Immediate treatment is needed because of the potentially life-threatening thoughts and behaviours associated with the disorder. Treatment comprises hospitalisation (usually in a highly monitored mother and baby treatment unit), medication (antidepressants and antipsychotics), and psychotherapy.

Range of symptoms

The symptoms of postpartum depression are similar to those of anxiety and general depression. Symptoms can make it difficult to complete day-to-day activities and routines, and can affect an individual’s relationship with their baby, partner, family, and friends. Typically, the symptoms include:

Negative feelings Intense irritability and anger.

Mood Swings Elation followed by enervation.

Depressed Mood Feeling unable or unwilling to cope.

Fatigue Ranging from lethargy to exhaustion.

Withdrawal From partner, family, and friends.

Appetite Loss of appetite or appetite for unhealthy foods.

Apathy Reduced interest in activities that used to bring enjoyment.

Fear Apprehensive about being a good parent.

Crying Excessive crying and feeling tearful.

Difficulty bonding Not feeling expected parental love for baby.

Sleep patterns Inability to sleep or sleeping too much.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive and behavioural therapies in a group, one-to-one, or as guided self-help; one-to-one counselling.

. Lifestyle management, such as talking to partner, friends, and family; resting; regular exercise; and eating healthily and regularly.

. Antidepressants alone or with psychotherapy.

DMDD (disruptive mood dysregulation disorder)

DMDD is a childhood disorder characterised by almost constant anger and irritability combined with regular and severe temper tantrums.

What is it?

DMDD is a recently identified disorder (2013) that children with a history of chronic irritability and serious temper outbursts are now recognised as having. The child is sad, bad tempered and/or angry almost every day. The outbursts are grossly out of proportion with the situation at hand, occur several times every week, and in more than one place (at home, school, and/or with peers). Strained interactions that occur only between a child and their parents, or a child and their teacher, do not indicate DMDD.

How is it diagnosed?

For a diagnosis of DMDD, the symptoms must be evident consistently for more than a year and interfere with a child’s ability to function at home and at school. One cause can be that the child misinterprets other people’s expressions, in which case training in facial-expression recognition can be offered. Diagnosed children are generally under the age of 10, but not younger than six or older than 18. One to three per cent of children under the age of 10 have symptoms.

Disruptive behaviour

Children with DMDD regularly have severe temper tantrums, inconsistent with their developmental stage, three or more times a week in at least two different settings. Typical behaviour includes destroying things or throwing things around the room, shouting abuse at teachers, peers, or parents, and being angry and irritable almost all of the time.

Children with DMDD were once identified as having paediatric bipolar disorder, but they do not present with the episodic mania or hypomania of that disorder. They are unlikely to develop bipolar but are at higher risk of depression and anxiety as adults.

☑ TREATMENT

. Psychotherapy for both child and family to explore emotions and develop mood management techniques.

. Lifestyle management including positive behaviour support to establish better communication and minimise outburst triggers.

. Antidepressants or antipsychotics to support psychotherapy.

SAD (seasonal affective disorder)

SAD is a form of seasonal depression linked to changing levels of light that typically starts in autumn as the days shorten. It is also known as “winter depression” or “hibernation state”.

What is it?

The nature and severity of SAD vary from person to person, and for some it can have a significant impact on their day-to-day life. Typically, the symptoms come and go with the seasons, and always begin at the same time of year, often in the autumn. Symptoms include low mood, a loss of interest in everyday activities, irritability, despair, guilt, and feelings of worthlessness. People with SAD lack energy, feel sleepy during the day, sleep for longer than normal at night, and find it hard to get up in the morning. As many as one in three people are affected.

SAD’s seasonal nature can make diagnosis difficult. Psychological assessment looks at a person’s mood, lifestyle, diet, seasonal behaviour, thought changes, and family history.

Seasonal cause and effect

Sunlight level affects a part of the brain called the hypothalamus and alters the production of two chemicals: melatonin (which controls sleep) and serotonin (which changes mood).

Secretion of melatonin by the pineal gland is triggered by darkness/inhibited by light and controlled by the hypothalamus.

Summer pattern

. Melatonin drops so person has more energy.

. Serotonin production increases, improving mood and outlook.

. Sleep is good, but not excessive, so person has more energy.

. Diet improves as cravings subside.

. Improved energy results in increased activity and more social contact.

Winter pattern

. Melatonin increases so person is tired and wants to sleep.

. Serotonin production drops, causing person to feel low.

. Desire to stay in bed and sleep can lead to reduced social contact.

. Craving carbohydrates can cause overeating and weight gain.

. Constant daytime fatigue affects work and family life.

☑ TREATMENT

. Psychotherapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy and counselling.

. Lifestyle management by improving access to light – sitting near windows when inside, using a sunlight-simulating light bulb at the correct level of lux, and daily outdoor activity.

Panic disorder

Panic attacks are an exaggerated reaction to the body’s normal response to fear or excitement. With panic disorder, a person regularly experiences such attacks for no obvious reason.

What is it?

The normal reaction to fear or excitement causes the body to produce the hormone adrenaline to prepare for “fight or flight” from the source of fear. If a person has a panic attack, apparently normal thoughts or images trigger the brain’s fight-or-flight centre, resulting in adrenaline racing around the body causing symptoms such as sweating, increased heart rate, and hyperventilation. Attacks last about 20 minutes and can be very uncomfortable.

The individual may misinterpret these symptoms, saying they feel as if they are having a heart attack. The fear can further activate the brain’s threat centre, so more adrenaline is produced, worsening symptoms.

Individuals who have recurring panic attacks can fear the next one so much that they live in a constant state of “fear of fear”. Attacks may, for example, be set off by fear of being in a crowd or a small space, but often they are triggered by internal sensations that have nothing to do with the outside world. As a result, everyday tasks can become difficult and social interactions daunting. Those with panic disorder may avoid certain places or activities, so the problem persists because the person can never “disconfirm” their fear.

What are the causes?

One in ten people suffer from occasional panic attacks; panic disorder is less common. Traumatic life experiences, such as a bereavement, can trigger the disorder. Having a close family member with panic disorder is thought to increase the risk of developing it. Environmental conditions such as high carbon dioxide levels may cause attacks. Some illnesses, for example an overactive thyroid, can produce similar symptoms to panic disorder, and a medical doctor will rule such illnesses out before making a diagnosis.

Constant cycle of anxiety and fear

A person perceives a threat and starts to panic. The physical symptoms develop, worsening the anxiety and therefore the symptoms, which in turn increase the likelihood of a repeat attack.

✔ SYMPTOMS OF A PANIC ATTACK

The symptoms result from the action of the autonomic nervous system – the part not under conscious control.

Increased heart rate Adrenaline causes the heart to pump faster to move blood containing oxygen to where it is needed. This can result in chest pains.

Feeling faint Breathing is faster and shallower to increase oxygen, causing hyperventilation and light-headedness.

Sweating and pallor Sweating increases to cool the body. The person may also become pale as blood is diverted to where it is needed most.

Choking sensation Faster breathing feels like choking – oxygen level rises but not enough carbon dioxide is exhaled.

Dilated pupils The pupil (black part of the eye) becomes dilated to let in more light, making it easier to see to escape.

Slowed digestion As digestion is not crucial for “flight”, it slows. The sphincters (valves) relax, which makes the sufferer feel nauseous.

Dry mouth The mouth can feel very dry as body fluids are concentrated in the parts of the body where they are most needed.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to identify triggers, prevent avoidance behaviour, and learn to disprove feared outcomes.

. Support groups to meet others with the disorder and get advice.

. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Specific phobias

A phobia is a type of anxiety disorder. Specific phobias manifest themselves when a person anticipates contact with, or is exposed to, the object, situation, or event they fear.

What are they?

Specific, simple phobias (as opposed to the complex ones, agoraphobia, and claustrophobia) are the most common psychological disorders in children and adults. A phobia is much more than fear and arises when a person develops an exaggerated or unrealistic sense of danger about a situation or object. The fear may not make any sense, but the individual feels powerless to stop it. Anticipated or actual exposure (even to an image) can cause extreme anxiety or a panic attack. Symptoms include rapid heart rate, breathing difficulties, and a feeling of being out of control.

A combination of genetics, brain chemistry, and other biological, psychological, and environmental factors can give rise to a phobia. It can often be traced back to a frightening event or stressful situation a person either witnessed or was involved in during early childhood. A child can also “learn” a phobia through seeing other family members demonstrate phobic behaviour.

Specific phobias often develop during childhood or adolescence and may become less severe with age. They can also be associated with other psychological conditions such as depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

How are they diagnosed?

Many affected individuals are fully aware of their phobia, so a formal diagnosis is not necessary, and they do not need treatment – avoiding the object of their fear is enough to control the problem. However, in some people habitual avoidance of a feared object can also maintain or worsen the phobia, and seriously impact aspects of their lives. A patient can be referred to a specialist with expertise in behavioural therapy.

Types of specific phobia

There is a wide variety of objects or situations that can trigger a phobia. Specific, so-called simple, phobias fall into five groups: blood-injection-injury, natural environment, situational, animal, and “other” types. With the exception of the first type, specific phobias are two to three times more common in females than males.

Blood-injection-injury A unique group of phobias in which the sight of blood or needles causes a vasovagal reaction (a reflex action that slows down the heart rate, reducing blood flow to the brain) that can result in fainting. Unlike all other phobias, this is as common in males as it is in females.

Natural Environment A person with a phobia from this group has an irrational fear of a natural event, which they often associate with imagery of potentially catastrophic outcomes. Examples include storms, deep water, germs, and fear of heights, such as being near a cliff edge.

Situational These are phobias of being in a specific situation, which can range from visiting the dental surgery to stepping into an old lift, flying, driving over a bridge or through a tunnel, or getting into a car.

Animal This group of phobias includes insects, snakes, mice, cats, dogs, and birds, among other animals. It could be rooted in a genetic predisposition for survival from animals that were a threat to human ancestors.

Other Phobias Thousands of people are tormented by an array of phobias, including the fear of vomiting; a specific colour, for example anything that is yellow or red (including foodstuffs); the number 13; the sight of a belly button or toes; sudden loud noises; fancy dress characters, such as clowns; trees; or contact with cut flowers.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to overcome a phobia using a system of graded steps to work towards the goal of confronting the feared object or situation without fear; anxiety management techniques to master each step.

. Mindfulness to raise tolerance of anxiety and thoughts or images associated with the distress.

. Anti-anxiety medication or antidepressants alongside therapy if the phobia is impairing day-to-day living.

Agoraphobia

This is an anxiety disorder characterised by a fear of being trapped in any situation in which escape is difficult or rescue is unavailable if things go wrong.

What is it?

Agoraphobia is a complex phobia that is not, as many think, simply a fear of open spaces. The individual dreads being trapped and avoids whatever triggers the terror of being unable to escape. The result can be a fear of travelling on public transport, being in an enclosed space or crowd, going shopping or to health appointments, or leaving the house. The associated panic attack brought on by such an experience is accompanied by negative thoughts – for example, the person may think that as well as being trapped they are going to look ridiculous, because they are out of control in public. The symptoms, or fear of them, are disruptive and result in avoidance behaviours that make leading a normal life hard.

Agoraphobia can develop if an individual has a panic attack, then worries excessively about a repeat experience. In the UK, one-third of those who have panic attacks go on to develop agoraphobia. Biological and psychological factors are the probable cause. Experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, mental illness, or an unhappy relationship may play a part.

Treatment can help – about one-third are cured and 50 per cent find that symptoms improve. Other conditions are first excluded by a medical doctor that may be causing the symptoms.

Types of symptoms

The symptoms of agoraphobia are classified into three types: the physical symptoms that a person experiences in the feared situation; behavioural patterns associated with the fear; and cognitive symptoms – the thoughts and feelings a person has anticipating or living with the fear. The combination can make it difficult for a person to function day to day.

Physical Rapid heart and breathing rate, chest pain, dizziness, shaking, feeling nauseous, and breathing problems.

Behavioural Excessive planning to avoid crowds, queues, and public transport, or not going out at all or only with a trusted person.

Cognitive Predictions of shaming by others, over-thinking potential disasters, catastrophic thoughts of being trapped or injured, and feeling out of control.

☑ TREATMENT

. Intensive psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioural therapy to explore the thoughts that maintain the phobia; behavioural experiments to gather evidence that defuses strongly held beliefs.

. Self-help groups using safe visual material to work on exposure to the feared situation; teaching how to manage a panic attack by breathing slowly and deeply.

. Lifestyle management such as exercise and a healthy diet.

Claustrophobia

An irrational fear of being trapped in a confined space or even the anticipation of such a situation, claustrophobia is a complex phobia that can cause extreme anxiety and panic attacks.

What is it?

For a person with claustrophobia, being confined induces physical symptoms similar to those of agoraphobia (above). The fear also increases negative thoughts of running out of oxygen or suffering a heart attack with no chance of escape. Many individuals also experience feelings of dread and fear of fainting or losing control.

Claustrophobia may be caused by conditioning following a stressful situation that occurred in a small space. This might be traced back to childhood, when, for example, an individual was confined in a tiny room or was bullied or abused. The condition can also be triggered by unpleasant experiences at any stage of life, such as turbulence on a flight or being trapped in a lift. The individual fears a repeat of being confined as well as overimagining what could happen in a small space. As a result, they plan their daily activities carefully to minimise the likelihood of “becoming trapped”.

Sometimes claustrophobia is observed in other family members, which suggests a genetic vulnerability to the disorder and/or a learned associated response.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to re-evaluate negative thoughts through exposure to the feared situation in small steps, so the individual realises that the worst fear does not occur.

. Anxiety management to cope with anxiety and panic by using breathing techniques, muscle relaxation, and visualising positive outcomes.

. Anti-anxiety medication or antidepressants prescribed in extreme cases.

GAD (generalised anxiety disorder)

People with this disorder experience continual unrestrained and uncontrollable worry (even when no danger is present), to the extent that day-to-day activity and functioning can become impaired.

What is it?

An individual with GAD worries excessively about a wide range of issues and situations. Symptoms include “threat” reactions such as heart palpitations, trembling, sweating, irritability, restlessness, and headaches. GAD can also cause insomnia and difficulty in concentrating, making decisions, or dealing with uncertainty.

The person may become obsessed with perfectionism, or with planning and controlling events. The physical and psychological symptoms can have a debilitating effect on social interactions, work, and everyday activities, leading to lowered confidence and isolation. Worries may revolve around family or social matters, work, health, school, or specific events. A person with GAD experiences feelings of anxiety most days, and as soon as they resolve one worry another appears. They overestimate the likelihood of bad or dangerous things happening and predict the worst possible outcome. The individual may even report positive beliefs about the helpfulness of worry, such as: “Worrying makes it less likely that bad things will happen”. Long-term or habitual avoidance of fearful situations or places compounds the disorder because the individual never gathers evidence that their fears are unfounded, so maintaining the worry.

Women are 60% more likely to develop GAD than men.

Balancing worries

Anxiety becomes a problem when a person is weighed down with worries for the majority of days in a six-month period, or longer.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to identify triggers, negative thoughts, habitual avoidance, and safety behaviours.

. Behavioural therapy to identify new behavioural goals, with achievable steps.

. Group therapy with assertiveness training and building self-esteem to help counteract unhelpful beliefs and unfounded fears.

Social Anxiety Disorder

Individuals with this condition experience an overwhelming fear of being judged or of doing something embarrassing in social situations. The disorder can cause disabling self-consciousness.

What is it?

An individual with social anxiety disorder (also called social phobia) experiences excessive nerves or dread of social situations. They may be anxious only in specific circumstances, such as speaking or performing in public, or experience distress in all social situations.

The person tends to be extremely self-conscious and worries about others evaluating them negatively. They dwell on past social incidents, obsessing about how they might have come across. Social anxiety causes the person to overplan and rehearse for anticipated situations, which may lead to odd or awkward behaviour. Individuals may then gather evidence to support their fears, because difficult situations often arise as a result of the person’s anxiety or over-rehearsal.

This disorder leads to isolation and depression and can seriously affect social relationships. It can also have a negative impact on performance at work or school.

Symptoms before social interaction The individual may prepare and rehearse excessively in advance, planning topics of conversation or how to present themselves in a specific way.

During interaction Physical symptoms such as trembling, rapid breathing, racing heart, sweating, or blushing occur as the body’s “fight or flight” system is activated. In extreme cases, the person may experience a panic attack.

After interaction The person conducts a detailed, negative, and self-critical appraisal of the social situation, dissecting conversations and body language and giving them a negative slant.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to recognise and change negative thought patterns and behaviours.

. Group therapy for the opportunity to share problems and practise social behaviour.

. Self-help including affirmations, rehearsing before social events, and using video feedback to disprove negative assumptions.

Separation anxiety disorder

This anxiety disorder can develop in children whose natural concern about being separated from their parent, primary caregiver, or home persists beyond the age of two years.

What is it?

Separation anxiety is a normal adaptive reaction that helps to keep babies and toddlers safe while they attain competence to cope with their environment. However, it can be a problem if it persists for more than four weeks and interferes with age-appropriate behaviour.

The child becomes distressed when they need to leave a primary carer and fears that harm will come to that person. Situations, such as school and social occasions can also be a trigger. Affected children may experience panic attacks, disturbed sleep, clinginess, and inconsolable crying. They may complain of physical problems such as stomach-ache, headache, or just feeling unwell for no apparent reason. Older children may anticipate feelings of panic and struggle to live and travel independently.

Separation is the most common anxiety disorder in children under 12 years old. It can also affect older children, and it may be diagnosed in adulthood. The disorder can develop after a major stressor such as the loss of a loved one or pet, moving home, changing school, or parents’ divorce. Overprotective or intrusive parenting can contribute.

Separation anxiety is very treatable with behavioural therapies that include building planned separations into times of the day when the person is feeling least vulnerable.

Being alone

Worries about losing their primary carer are common and the child may relive their daytime fears in nightmares. They may refuse to sleep alone or suffer from insomnia.

Vivid fears – The child worries excessively about being detached from their primary carer – even if only in a separate room.

Unwanted burden – Anxious feelings may manifest themselves as physical pains as the child struggles to fix their panic of separation into something tangible.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety management; assertiveness training for older children and adults.

. Parent training and support to promote and reinforce short periods of separation that are then extended gradually.

. Anti-anxiety medication and antidepressants for older individuals in combination with environmental and psychological interventions.

Selective mutism

This is an anxiety disorder in which people are unable to talk in certain social situations but are able to speak at other times. It is usually first recognised between the ages of three and eight years.

What is it?

Selective mutism is associated with anxiety, and children who are affected by it struggle with excessive fears and worries. They are generally able to speak freely where they feel comfortable but are unable to talk in specific situations, when they do not engage, go still, or have a frozen facial expression when expected to talk. This inability to speak is not the result of a conscious decision or a refusal.

The mutism can be triggered by a stressful experience, or it can stem from a speech or language disorder, or hearing problem, which makes social situations involving communication particularly stressful. Whatever the cause, everyday activities are difficult as are relationships within the family, nursery, or school. Treating the condition can prevent it persisting into adulthood – the younger the child is when diagnosed the easier it is to treat.

If symptoms persist for more than a month, the child should be seen by a medical doctor, who can refer them for speech and language therapy. A specialist will ask whether there is a history of anxiety disorders, a likely stressor, or a hearing problem. Treatment depends on how long the child has had the condition, the presence of learning difficulties or anxieties, and the support that is available.

State of fear

Children with selective mutism literally “freeze” when they are expected to talk and make little or no eye contact. The condition is more common in children who are learning a second language.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy using positive and negative reinforcements to build speech and language skills; graded exposure to specific situations to reduce anxiety, removing pressure on the child to speak.

. Psychoeducation can provide information and support for parents and carers; relieve general anxiety; and reduce chances of the disorder persisting into adulthood.

OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder)

This is a debilitating anxiety-related condition characterised by intrusive and unwelcome obsessional thoughts that are often followed by repetitive compulsions, impulses, or urges.

What is it?

OCD is often marked by thoughts that reflect an excessive sense of responsibility for keeping others safe and an overestimation of the perceived threat an intrusive thought signifies. OCD is clinical and often starts with an obsessional thought, which the person focuses on, in turn raising anxiety levels. Checking everything is in order and following rituals can provide relief, but the distressing thought returns. The obsessive thoughts and compulsions are time-consuming and individuals may struggle to function day to day or have a disrupted social or family life. The disorder may be triggered by an event in the person’s history that they felt highly responsible for. Family history, differences in the brain, and personality traits also play a part. An examination of thoughts, feelings, and behaviour patterns determines OCD, but its similarity to other anxiety disorders can make diagnosis difficult.

With pure OCD, a person has intrusive and disturbing thoughts about harming people, but rather than performing observable compulsions, their compulsions take place in the mind.

OBSESSIONS (THOUGHTS)

Fear of causing harm Excessive attention paid to thoughts about actions that could cause harm.

Intrusive thoughts Obsessive, repetitive, and even disturbing thoughts about causing harm.

Fear of contamination Thinking that something is dirty or germ-ridden and will cause illness or death to the person or someone else.

Fear related to order or symmetry Concern that harm could result unless tasks are done in a specific order.

COMPULSIONS (BEHAVIOURS)

Rituals Following rituals such as counting or tapping to prevent harm and provide relief from the cycle of fear.

Constant checking Examining household appliances, lights, taps, locks, windows (to counter fear of causing harm by fire), driving routes (fear of having run a person over), or people (fear of upsetting someone).

Correcting thoughts Trying to neutralise thoughts to prevent disasters.

Reassurance Repeatedly asking others to confirm everything is OK.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy involving exposure to triggers and learning how to control responses.

. Anti-anxiety medication and/or antidepressants to help relieve symptoms of depression and anxiety.

. Specialist residential treatment in addition to therapy and medication for extremely severe cases of OCD.

Hoarding disorder

Also known as compulsive hoarding, this disorder is characterised by the excessive acquisition of, and/or the inability or unwillingness to dispose of, large quantities of objects.

What is it?

An individual with hoarding disorder does not discard worn-out possessions, for fear of either needing them again or of something bad happening to other people if they get rid of anything. The person stores sentimental items as they believe that discarding them will stop emotional needs being met. The individual continues to accumulate items even when space is running out. Hoarding can be hard to treat because the person does not see it as a problem and experiences such overwhelming discomfort at reducing the clutter that they avoid doing so. Alternatively, the person may be aware of the problem but too ashamed to seek help or advice.

Hoarding disorder may begin as a way of coping with a stressful life event. Hoarding may be part of other disorders such as OCD, depression, or psychotic disorders. In medical assessment, the doctor questions the person about their feelings on acquiring objects and their overestimation of responsibility for causing harm by discarding items.

Living with hoarding

A person with hoarding disorder may let junk mail, bills, receipts, and heaps of paper pile up. The resulting clutter can pose a health and safety risk and makes it hard to move from room to room, which is distressing for the individual and affects their, and their family’s, quality of life. This may lead to isolation and impaired or difficult relationships with other people.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to examine and weaken the thoughts that maintain the hoarding behaviour and allow adaptive or flexible alternatives to emerge.

. Lifestyle management at home to motivate reducing clutter for health and safety reasons.

Antidepressants to decrease the associated anxiety and depression.

BDD (body dysmorphic disorder)

In this condition a person has a distorted perception of how they look. The individual typically spends an excessive amount of time worrying about their appearance and how others view them.

What is it?

BDD is an anxiety disorder that can have a huge impact on daily life. An individual with BDD worries obsessively about how they look. They often focus on a specific aspect of their body, for example, viewing a barely visible scar as a major flaw or seeing their nose as abnormal, and are convinced that others view the “flaw” in the same way. The person may spend a great deal of time concealing an aspect of their appearance, seeking medical treatment for the part of the body believed to be defective, and/or diet or exercise excessively.

BDD affects about one in every 100 people in the UK, can occur in all age groups, and is seen in males and females in equal numbers. It is more common in people with a history of depression or social anxiety disorder, and it often occurs alongside OCD or GAD (see above). BDD may be due to brain chemistry or genetics and past experiences may play a role in triggering its development. In medical assessment, the doctor asks the person about their symptoms and how they affect them and may refer them to a mental health specialist for further treatment.

Breaking the cycle

Treatment for BDD can be highly successful and focuses on breaking the cycle of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that maintain it. The length of time treatment takes depends on the severity of the condition.

Consider a person with a negative self-image. The cycle starts with a trigger and moves towards efforts to change appearance.

Trigger Seeing their reflection, misinterpreting body language, or someone’s passing comment can start the cycle.

Automatic Thoughts Negative thoughts dominate, for example, “I am defective, defective people are worthless, so I am worthless”.

Low Mood The perceived constant social threat leads to chronic anxiety and depression.

Efforts To Change Appearance Safety behaviours or social avoidance prevail. The person may apply excessive make-up or use clothing to conceal the perceived defective attribute; seek cosmetic surgery; use extreme diet and exercise to change body shape; and avoid social situations, so increasing feelings of isolation.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive behavioural therapy to identify self-appraisal related to the problem body part and weaken the beliefs that maintain it.

. Antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication alongside therapy.

Illness anxiety disorder

Previously known as hypochondria, this condition involves a person worrying excessively about becoming seriously ill, even if thorough medical examinations reveal nothing.

What is it?

Hypochondria is considered to be two separate conditions: illness anxiety disorder if there are no symptoms or they are mild, or somatic symptom disorder, if there are major physical symptoms causing emotional stress. People with illness anxiety disorder become excessively preoccupied with their health. Some have exaggerated feelings about an existing condition (about 20 per cent do have heart, respiratory, gastrointestinal, or neurological problems). Others experience unexplained symptoms. They convince themselves that these symptoms indicate a serious illness that has been missed by medical professionals and their teams.

Illness anxiety is a long-term condition that fluctuates in severity and may worsen with age or stress. It can be triggered by a major life event. Someone who is anxious or depressed is more prone to the disorder. Assessment and treatment focus on stopping avoidance and reassurance behaviours, re-evaluating health beliefs, and increasing the person’s tolerance of uncertainties.

Endless checks

Disbelief in medical opinion reaffirms the person’s anxiety and results in extra focus on the body part or illness, which causes panic and physical symptoms. Safety behaviours, such as avoiding situations for fear of exposure to disease, and reassurance from others provide brief respite.

Typically, there is a pain or sensation which instigates the trigger. The person then misinterprets the signs by being convinced they have a serious illness. They then research that illness extensively. Frequent body checks and possible avoidance measures are made, despite a medical doctor and other medical professionals finding no sign of illness.

☑ TREATMENT

. Behavioural therapies such as attention training to stop a person over-attending to body sensations and help re-evaluate beliefs.

. Antidepressants prescribed alongside therapy.

PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder)

This is a severe anxiety disorder that may develop any time after a person experiences or witnesses a terrifying or life-threatening event, or series of events, over which they have little or no control.

What is it?

PTSD is seen in people who have been in military combat or a serious incident, or suffered prolonged abuse or the unexpected injury or death of a family member. The event itself activates the fight-or-flight reflex in the brain and body, putting the person on hyperalert to deal with the consequences of the trauma and protect them from a repeat of the episode. An individual with PTSD feels that the threat remains, so their heightened response is maintained, causing an array of unpleasant symptoms including panic attacks, involuntary flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance and emotional numbing, anger, jumpiness, insomnia, and difficulty concentrating. These symptoms usually develop within a month of the event (but may not appear for months or years) and last for more than three months. PTSD can lead to other mental health problems and excessive alcohol and drug use is common.

Watchful waiting is advisable at first to see if the symptoms subside within three months as treatment too early can exacerbate PTSD.

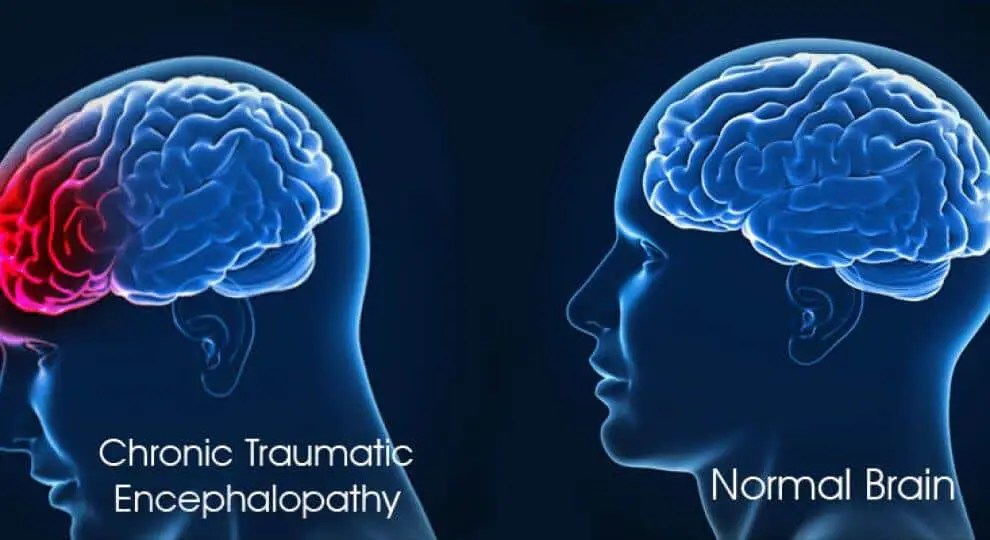

Brain changes

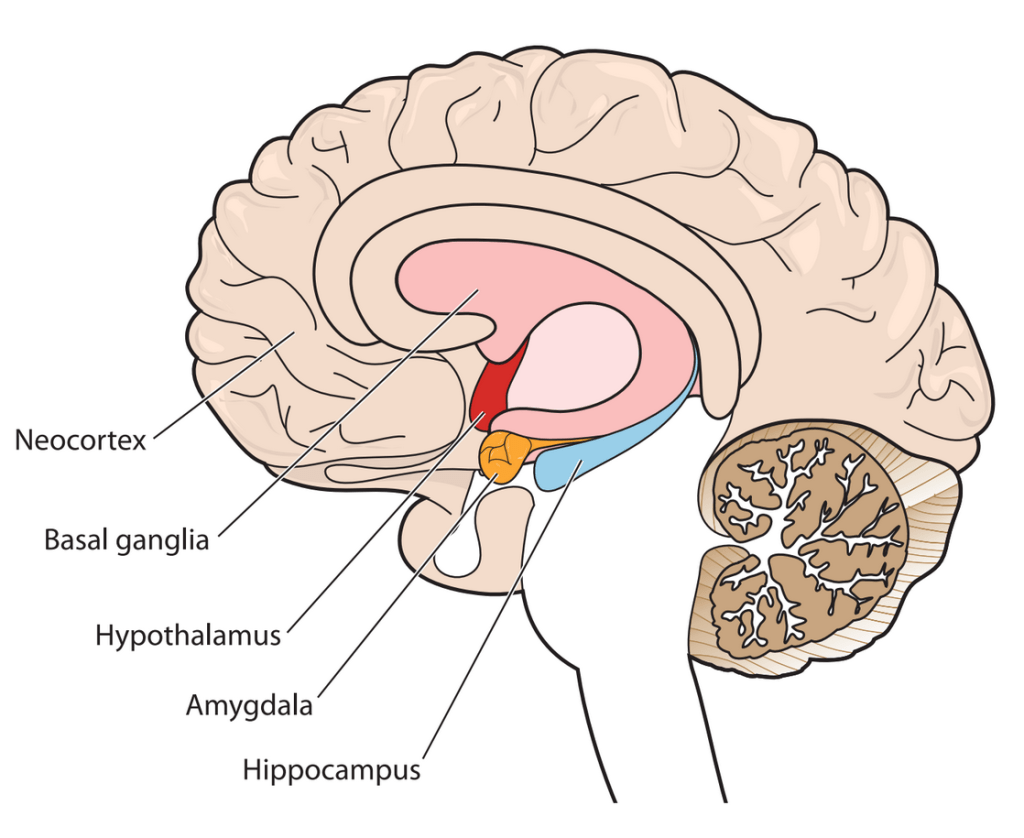

PTSD is a survival reaction. The symptoms result from an aim to help survive further traumatic experiences and include raised levels of stress hormones and other changes in the brain:

Hippocampus – PTSD increases stress hormones, which reduce activity in the hippocampus and make it less effective in memory consolidation. Both the body and mind remain hyperalert because its decision-making ability is reduced.

Prefrontal cortex – Trauma affects the function of the prefrontal cortex, changing behaviours, personality, and complex cognitive functions such as planning and decision-making.

Hypothalamus – In PTSD, the hypothalamus sends signals to the adrenal glands (on the kidneys) to release the hormone adrenaline into the bloodstream and increase the chances of survival.

Amygdala – PTSD increases the function of the amygdala, activating the fight-or-flight response and increasing sensory awareness.

☑ TREATMENT

. Trauma-focused therapy such as cognitive behaviour therapy, or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, to help reduce the sense of current threat by working on memory of the event.

. Compassion-focused therapy to self-soothe from shame-based thoughts and images. Group therapy for vulnerable groups such as war veterans.

ASR (acute stress reaction)

Also called acute stress disorder, ASR can appear quickly after an exceptional physical or mental stressor such as bereavement, road traffic incident, or assault, but does not usually last long.

What is it?

Symptoms of ASR are anxiety and dissociative behaviour following exposure to a traumatic and unexpected life event. The person may feel disconnected from themselves, have difficulty handling emotions, suffer mood swings, become depressed and anxious, and may have panic attacks. They often experience difficulty sleeping, poor concentration, and recurrent dreams and flashbacks, and may avoid situations that trigger memories of the event. Some individuals have psychological symptoms such as raised heart rate, breathlessness, excessive sweating, headaches, chest pain, and nausea.

ASR is described as acute because the symptoms come on fast, but do not usually last. Symptoms of ASR can begin within hours of the stress and are resolved within a month; if they last longer, they may turn into PTSD (see above).

ASR may resolve without therapy. Talking things over with friends or relatives can help those with the disorder understand the event and put it into context. Individuals may benefit from psychotherapies too.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that 80% of people with ASR develop PTSD 6 months later.

How does ASR differ from PTSD?

ASR and PTSD are similar, but the timeframes are different. The symptoms of ASR occur within a month of an event, and they usually resolve within the same month. The symptoms of PTSD may or may not develop within a month of the event or events. PTSD is not diagnosed unless the symptoms have been evident for more than three months. There is an overlap between what the symptoms are. However, in ASR symptoms involve feelings, such as dissociation, depression, and anxiety, predominate. With PTSD the symptoms relate to a prolonged or persistent response to the fight-or-flight mechanism. There is a higher risk of ASR developing in a person who has had PTSD or mental health issues in the past, and ASR can lead to PTSD.

☑ TREATMENT

. Psychotherapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy to identify and re-evaluate thoughts and behaviours that maintain anxiety and low mood.

. Lifestyle management including supportive listening and stress-relieving practices such as yoga or meditation.

. Betablockers and antidepressants to ease physical symptoms in combination with psychotherapy.

Adjustment disorder

This is a short-term, stress-related psychological disorder that can follow a significant life event. Typically, a person’s reaction is stronger, or more prolonged, than expected for the type of event.

What is it?

Any stressful event can trigger anxiety, difficulty sleeping, sadness, tension, and inability to focus. However, if an individual finds an event especially hard their reaction can be stronger and persist for months. In a child, the disorder can follow family conflicts, problems at school, and hospitalisation. The child may become withdrawn and/or disruptive and complain of unexplained pain or illness. Adjustment disorder is not the same as PTSD or ASR as the stress trigger is not as severe. It normally resolves within months as a person learns how to adapt to a situation and/or the stressor is removed. There is no way to predict whether one person is more likely to develop adjustment disorder than another. It is a result of how they respond to an event and their personal history.

A medical doctor first assesses whether an individual’s symptoms may be due to another condition, such as ASR, before referring them for a psychological assessment.

Causes and outcome

Some life events are known to lead to adjustment difficulties of varying severity. Examples are the death of a friend or family member, divorce or relationship breakdown, moving home, illness or injury, financial worries, or job stress.

. Symptoms begin within 3 months The onset can be traced to an event and symptoms are more severe than expected. They include defiant, impulsive behaviour, sleeplessness, crying, feeling sad and hopeless, anxiety and muscle tension.

. Symptoms resolve in 6 months With a further three months of therapy and the removal of the stressor, a person can learn to turn negative thoughts into healthy actions, to change how they respond to stress.

☑ TREATMENT

. Psychotherapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy, and/or family or group therapies to help identify and respond to stressors.

. Antidepressants to lessen symptoms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia alongside a psychotherapy.

Reactive attachment disorder

This disorder can result in children who do not bond with a caregiver in infancy. Unidentified reactive attachment disorder can be a precursor to lifelong impaired personal development.

What is it?

Attachment theory states that developing a strong emotional and physical bond with a primary caregiver is key to a child’s healthy personal development. Without such a bond a child can become increasingly detached, withdrawn, and distressed, and the physical symptoms relating to stress become obvious.

Persistent disregard of a child’s basic physical needs, frequent changes of primary caregivers, and childhood abuse can disrupt a child’s ability to form social and emotional bonds. The child can develop markedly disturbed ways of relating socially and may be unable to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Disinhibited responses, such as a disregard for convention and impulsive behaviour, used to be included in the medical assessment of this disorder, but these are now considered as a separate diagnosis of disinhibited social engagement disorder.

Associated disorders

Undiagnosed reactive attachment disorder is an underlying factor in a number of psychological problems that emerge in childhood or adulthood under clinical assessment:

. Depression This can develop because a person with reactive attachment disorder sees a constant disparity between expectation and reality.

. Learning difficulties Social isolation creates a hostile environment that can make an individual more likely to have developmental disorders.

. Low self-esteem Without any positive reciprocal interactions in infancy, neutral or negative ones can predominate later, which can affect self-esteem.

. Relationship issues Not developing healthy attachments in childhood makes it difficult to form meaningful relationships in adulthood.

. Social difficulties If a person feels different from their peers, they can be disruptive and are more susceptible to isolation or bullying.

. Substance abuse Individuals who have suffered a disrupted infancy or childhood commonly seek support through drugs.

Long-term impact

Early neutral, negative, or even hostile environments are likely to have a long-term negative impact and affect a person right through to adulthood. An individual’s ability to maintain and make healthy relationships in later life is severely compromised. Reactive attachment disorder can develop in early infancy and the vulnerability it creates is associated with a wide range of disorders that affect both children and adults.

☑ TREATMENT

. Cognitive and behavioural therapies to examine habitual appraisals; dialectical behaviour therapy to help severely affected adults; family therapy to promote good communication; anxiety management, and positive behaviour support.

ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder)

This neurodevelopmental disorder is diagnosed in children with behavioural symptoms (inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and impulsivity) that are inconsistent with their age.

What is it?

This is a condition that makes it difficult for a child to sit still and concentrate and it is usually noticeable before the age of six. The effects of ADHD can persist into adolescence and adulthood. Adults may also be diagnosed with the pre-existing condition, when persistent problems in higher education, employment, and relationships reveal it. However, the symptoms may not be as clear as they are in children. The level of hyperactivity decreases in adults with ADHD, but they struggle more with paying attention, impulsive behaviour, and restlessness.

The evidence for what causes ADHD is inconclusive, but it is thought to include a combination of factors. Genetics may play a part, which explains why it runs in families. Observations of brain scans also indicate differences in brain structure and have identified unusual levels of the neurotransmitters dopamine and noradrenaline. Other possible risk factors include premature birth, low birthweight, and exposure to environmental hazards. The condition is more common in people with learning difficulties. Children with ADHD may also display signs of other conditions such as ASD, tic disorders or Tourette’s, depression, and sleep disorders. Surveys have shown that worldwide this condition affects more than twice as many boys as girls.

Identifying ADHD

A medical doctor in general practice cannot officially diagnose ADHD, but if they suspect the child has the disorder, they refer them for specialist assessment. The child’s patterns of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsive behaviour are observed over a six-month period before a treatment plan is prepared.

Hyperactivity

. Difficulties sitting still The child cannot stay seated (or quiet) in situations where it is expected, such as the classroom.

. Constant fidgeting The child may twitch limbs, torso, and/or head, whether sitting or standing.

. Lack of volume control The child shouts and makes loud noises during normal everyday activities.

. Little or no sense of danger This may result in the child running and climbing in environments where these behaviours are neither safe nor appropriate.

Inattentiveness

. Concentration difficulties This causes the child to make errors of judgment and mistakes. Alongside constant movement, this can cause injury.

. Clumsiness The child is prone to dropping and breaking things.

. Easily distracted The child appears not to be listening and is unable to complete tasks.

. Poor organisational skills The child’s inability to concentrate has an impact on organisational abilities.

. Forgetfulness This results in the child losing things.

Impulsivity

. Interrupting The child disrupts conversations regardless of the speaker or situation.

. Inability to take turns The child is unable to wait their turn in conversations and games.

. Excessive talking The child may change a topic often or focus obsessively on one.

. Acting without thinking The child is unable to wait in line or keep up with group pace.

MANAGING ADHD

There are a number of ways that parents can help their child to handle the condition.

. Create predictable routines to calm an ADHD sufferer. Timetable daily activities and keep them consistent. Make sure school timetables are clearly set out too.

. Set clear boundaries and make sure the child knows what is expected of them; praise positive behaviour straightaway.

. Give clear instructions, either visual or verbal, whichever the child finds easier to follow.

. Use an incentive scheme, for example, have a star/points chart whereby a child can earn privileges for good behaviour.

☑ TREATMENT

. Behavioural therapies to help the child and their family manage day to day; psychoeducation for families and carers.

. Lifestyle management such as improving physical health and reducing stress to calm the child.

. Medication can calm (not cure) the person so that they are less impulsive and hyperactive. Stimulants increase dopamine levels and trigger the area of the brain involved in concentration.

ASD (autism spectrum disorder)

ASD describes a spectrum (range) of lifelong disorders that affect a person’s ability to relate to other people and their emotions and feelings, making social interaction difficult.

What is it?

ASD is generally diagnosed in childhood and can present in a variety of ways. A parent or carer may notice that a baby does not use vocal sounds, or an older child has problems with social interaction and non-verbal communication. Symptoms such as repetitive behaviours, problems talking, poor eye contact, tidying or ordering rituals, bizarre motor responses, repetition of words or sentences, a restricted repertoire of interests, and sleep problems are common. Some children with ASD may also have depression.

Genetic predisposition, premature birth, fetal alcohol syndrome, and conditions such as muscular dystrophy, Down’s syndrome, and cerebral palsy are known to be associated with ASD. A medical doctor in general practice first examines the child to rule out physical causes for the symptoms, then refers them for specialist diagnosis. Information is gathered about all aspects of the child’s behaviour and development, at home and school. There is no cure, but specialised therapies such as speech therapy and physical therapy can help. One in every 100 people in the UK has ASD and is identified in more boys than girls.

Degrees of ASD

ASD manifests itself in different ways and to different degrees in each person. Autistic author and academic Stephen M. Shore said, “If you’ve met one individual with autism, you’ve met one individual with autism”.

HIGH FUNCTIONING AUTISM AND ASPERGER’S

High functioning autism (HFA) and Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) are both terms that are applied to people with characteristics of ASD, but who are of above average intelligence with an IQ of more than 70. However, they exist as two separate diagnoses, as those with HFA have delayed language development, which is not present in AS. Diagnoses of HFA or AS may be missed in children as they are socially awkward with a manner that is not easily understood. The ASD traits they share of perfectionism and obsessive interest in a particular subject can mean that they become expert in their area of interest. Like ASD, those with HFA or AS also require strict routines, have sensitivities to certain stimuli, awkwardness, and difficulty behaving appropriately and communicating in social situations; the severity of these symptoms will differ in each person. Long-term difficulties arise with social and intimate relationships, both at school and into adulthood.

Communication: Problems with language are common. Some people with ASD are fluent, while others are speech impaired. All tend to be literal and have difficulty with understanding humour, context, and inference.

Social interaction: Impaired social skills mean that a person with ASD cannot recognise another’s personal space or read body language. The person might think out loud or repeat what another person has said.

Repetitive behaviour: Repetitive behaviour traits are common. An individual may make repetitive movements such as hand flapping or rocking, or develop rituals such as lining up certain toys or flicking switches on and off.

Sensory skills: Heightened sensitivity to sound can cause a person to develop avoidance behaviours such as humming, covering their ears, or self-isolation in a preferred space to escape noise.

Motor skills: Difficulties with movement, such as coordination and motor planning, are common in children with ASD. Fine motor skills like handwriting may also be affected, which can hinder communication.

Perception: Impaired sensory and visual perception means that those with ASD miss non-verbal cues, can be unaware of lies, and usually have difficulty seeing a situation from another person’s perspective.

Hans Asperger, Austrian paediatrician, and researcher of autism, said of ASD: “In science or art, a dash of autism is essential.”

☑ TREATMENT

. Specialist interventions and therapies can assist in areas such as personal safety, hyperactivity, and sleep difficulties.

. Educational and behavioural programmes can support the learning of social skills.

. Medication can help with associated symptoms – melatonin for sleep problems, SSRIs for depression, and methylphenidate for ADHD.

Schizophrenia

This is a long-term condition that affects the way a person thinks. It is characterised by feelings of paranoia, hallucinations, and delusions, and impacts significantly on a person’s ability to function.

What is it?

The word schizophrenia comes from the Greek, and literally means “split mind”, which has led to the myth that people with the condition have split personalities, but they do not. Instead, they suffer from delusions and hallucinations that they believe are real. There are different types of schizophrenia. The main ones are Paranoid (hallucinations and delusions), Catatonic (usual movements, switching between being very active and very still), and Disorganised, which has aspects of both. Despite popular beliefs, individuals with schizophrenia are not always violent. They are however more likely to abuse alcohol and drugs and it is these habits, combined with their condition, that can cause them to become aggressive.

Schizophrenia appears to result from a combination of physical, genetic, psychological, and environmental factors. MRI scans have identified abnormal levels of neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin and unusual brain structure, and there might be a correlation between the condition and pregnancy or birth complications. It is also thought excessive cannabis use in young adulthood can be a trigger.

Popular theories regarding the causes of schizophrenia in the second half of the twentieth century included family dysfunction theories, such as the “double bind” (when people are faced with contradictory, irreconcilable demands for courses of action), high levels of parent/carer “expressed emotion” (not tolerating those with the disorder) and learning the schizophrenic role through labelling. Since then, mental health specialists have observed that hearing voices or feeling paranoid are common reactions to trauma, abuse, or deprivation. Stress can trigger acute schizophrenic episodes and learning to recognise their onset can help with management of the condition.

How is it diagnosed?

Schizophrenia is diagnosed through clinical interviews and specialist checklists during which the symptoms will be assessed. The earlier the condition is diagnosed, and treatment begun, the better, so that there is less time for its extreme impact on personal, social, and work life to build up. While schizophrenia is not curable, people can overcome it enough to function day to day. A personalised treatment plan that caters to the specific needs of the individual with schizophrenia is required for people with such a complex mental health issue.

Around 1.1% of the global adult population have schizophrenia.

Symptoms of schizophrenia

These are classified as positive or negative. Positive symptoms are psychotic additions to an individual while negative symptoms can look like the withdrawal or flat emotions seen with depression. Schizophrenia is likely if a person has experienced one or more symptoms from both domains for most of the time for a month.

Positive symptoms (psychotic)

These symptoms are classified as positive because they are additions to a person’s mental state and represent new ways of thinking and behaving that only develop with the condition:

. Hearing voices is common and can occur occasionally or all the time. The voices may be noisy or quiet, disturbing, or negative, known, or unknown, and male or female.

. Hallucinations involve seeing things that are not there, but seem very real to the person, and are often violent and very disturbing.

. Feeling sensations can cause a person to be convinced that they have unpleasant creatures such as ants crawling on or under their skin.

. Smelling and tasting things that cannot be identified can arise, and there may be difficulty discriminating between smells and tastes.

. Delusions – fixed beliefs – are held despite evidence to the contrary. The person may think they are famous and/or being chased or plotted against.

. Feelings of being controlled by, for example, a religious or dictatorial delusionist, can overwhelm a person. The beliefs can make them act differently.

Negative symptoms (withdrawal)

These symptoms are called negative because they represent a loss of certain functions, thoughts, or behaviours that a healthy person exhibits, but that are absent in those with schizophrenia:

. Difficulty communicating with others can result in changed body language, a lack of eye contact, and incoherence.

. “Flattened” emotions result in a significantly reduced range of response. The person will take no pleasure in activities.

. Tiredness may result in lethargy, change in sleep patterns, staying in bed, or sitting in the same place for long periods.

. Absence of willpower or motivation makes it difficult or even impossible for a person to engage in normal day-to-day activity.

. Poor memory and concentration mean that the individual is unable to plan or set goals and has difficulty keeping track of thoughts and conversations.

. Inability to cope with everyday tasks results in disorganisation. The individual stops looking after themselves, domestically or personally.

. Becoming withdrawn from social and community activities can disrupt the individual’s social life.

☑ TREATMENT

. Community mental health teams such as social workers, occupational therapists, pharmacists, psychologists, and psychiatrists work together to develop ways to help a person stay stable and progress.

. Medication in the form of antipsychotics is prescribed to reduce monthly positive symptoms, but it does not cure the condition.

. Cognitive behavioural therapy and the technique of reality testing can help with management of symptoms such as delusions. New developments use imagery to defuse stress that negative symptoms cause.

. Family therapy can improve relationships and coping skills within the family and educate anyone in a person’s care.

Anecdotal evidence suggests 1% of the population is likely to develop schizoaffective disorder.

Schizoaffective disorder

This is a long-term medical health condition in which a person suffers both the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia and the deregulated emotions that characterise bipolar disorder at the same time.

What is it?

While symptoms may vary from person to person, one episode will feature both psychotic and mood symptoms (manic, depressive, or both) for part of the time and a period with only psychotic or mood symptoms for most of the time over a period of at least two weeks.

Schizoaffective disorder can be triggered by traumatic events that took place when a person was too young to know how to cope or was not being cared for in a way that made it possible to develop coping skills. Genetics may play a part, too. It is more common in women and usually begins in early adulthood.

A mental health professional will assess the symptoms and want to know how long they have been present, and what triggers them. This chronic condition impacts on every aspect of a person’s life, but symptoms can be managed. Family interventions to raise awareness of the disorder can improve communication and support.

The different forms

People with this disorder experience periods of psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, with mood disorder symptoms – either of a manic type or a depressive type, but sometimes both. The condition features cycles of severe symptoms followed by periods of improvement.

Psychotic symptoms

. Hallucinations Hearing voices and seeing things that are not there.

. Delusions False, fixed beliefs in things that are not true.

Mood disorder symptoms

. Manic type is hyperactive, feels high, cannot sleep, and takes risks.

. Depressive type feels sad, empty, and worthless.

. Mixed type has symptoms of both depression and mania.

☑ TREATMENT

. Medication is needed long term, usually combinations of mood stabilisers plus antidepressants for depressive types or antipsychotics for manic types.

. Cognitive behavioural therapy can help a person make links between thoughts, feelings, and actions; learn the cues preceding behaviour change; and develop coping strategies.

Catatonia

An episodic condition that affects both behaviour and motor skills, catatonia is characterised by abnormal psychomotor functioning and extreme unresponsiveness when awake.

What is it?

Catatonia is a state of immobility that can persist for days or weeks. Those with the condition may have an extremely negative outlook and may not respond to external events, become agitated, have difficulty speaking due to extreme anxiety, and refuse to eat or drink. Symptoms also include feelings of sadness, irritability, and worthlessness, which can occur nearly every day. An individual may lose interest in activities, lose or gain weight suddenly, have trouble getting to sleep or out of bed, and feel restless. Decision-making is impaired and suicidal thoughts are common.

This condition can have a psychological or neurological cause and may be associated with depression or psychotic disorders. It is estimated that 10–15 per cent of people with catatonia also have symptoms of schizophrenia, while about 20–30 per cent of individuals with bipolar disorder may experience catatonia – mostly during their manic phase.

Diagnosing catatonia

A mental health professional observes an individual and looks for a number of symptoms. At least three out of the 12 symptoms described (below) must be present to confirm a diagnosis of catatonia:

Mutism Silent and apparently unwilling or unable to speak.

Echolalia Constantly repeats what other people have said.

Grimacing Makes distorted facial expressions that show disgust, dislike, and even pain.

Stupor Immobile, lacks expression, and does not respond to stimuli.

Catalepsy May be rigid, have a seizure, or be completely unresponsive in this trance-like state.

Waxy flexibility Limbs can be moved by someone else and will remain in the new position.

Agitation Movement may be purposeless and risky.

Mannerism Strikes poses or makes idiosyncratic movements.

Posturing Moves from one unusual position to another.

Stereotypy Frequent, persistent, repetitive movements.

Negativism Resistant to any outlook rather than a negative one.

Echopraxia Constantly mimics other people’s movements.

☑ TREATMENT

. Medication prescribed depends on the symptoms, but includes antidepressants, muscle relaxers, antipsychotics, and/or tranquillisers such as benzodiazepines, but these carry a risk of dependency. Outside help is needed to ensure compliance with medication and to teach living skills.

. Electroconvulsive therapy may be used when medication is ineffective. This involves transmitting an electric current through the person’s brain.

Delusional disorder

This is a very rare form of psychosis that causes a person to experience complex and often disturbed thoughts and delusions that are not true or based on reality.

What is it?