INTRODUCTION

FOR those people who grew up in the 1970s there was no internet, no World Wide Web, and the very first affordable home computers were just starting to emerge. In those days you had to be a serious geek to be into computers. Some fanatics were able to build bizarre robots, programmed early computers, and wrote simple computer games. Artificial intelligence – getting computers to think, to simulate biological behaviour, and to control robots – was a childhood passion for those enthused in the subject and prolific at home with the computer.

And then things changed. Quite dramatically. Today we live in a science-fiction story come true. Computers rule the world. Data floods from everything we do. Robots are building our products in factories. Our homes are computerised and we can talk to these digital home assistants, receiving detailed and coherent replies. Behind the scenes, artificial intelligence is making everything work. What was once a childhood passion for a few is now not only mainstream, but also considered one of the most important kinds of technology being created today.

You cannot live in the modern world without interacting with, or being impacted by, AI and robots. Every time you make a purchase, AIs are handling your money, checking for fraud, using your data to understand you better, and recommending new products to you. Every time you drive a car, AIs are helping the vehicle to proceed safely, they’re watching you from road cameras and automatically changing speed limits, they’re detecting your licence plate, and monitoring your movements. Every time you post something on social media, AIs may trawl through the text to understand your sentiment on specific topics. As you browse the internet and read news articles or blogs, AIs monitor your activity and try to please you by feeding you more of the content you prefer. Every time you take a photo, AIs adjust the camera settings and ensure the best possible picture is taken – and then can identify everyone in the picture for you. Face recognition, speech understanding, automatic bots that answer your questions online or by phone – all performed by AIs. Inside your home you have smart TVs, computerised fridges, washing machines, central heating, air conditioning systems – all AI robotic devices. The world economy is managed by AIs, financial trading is performed by AIs, and decisions about whether you should or should not be accepted for financial products are made by AIs. Your future anti-viral and antibacterial drugs are being designed by AI. Your services of water, electricity, gas, mobile phone, and internet connections are all adjusted by smart AI algorithms that try to optimise supply while minimising waste. You interact with a thousand AIs a day and you are blissfully unaware of them all.

On this page I’ll explain a little bit about how this has happened, how it works, and what it means. I will not bore the reader with detailed technical descriptions, nor explain every single AI technique or AI pioneering method. That would take a thousand volumes or more, with more innovations being made every day (progress is fast!). Instead my aim here is to take you on a journey through this strange world of computers, robots, and building brains, by explaining some of the fundamental ideas behind artificial intelligence and robotics. This journey may sometimes be a rollercoaster, for AI has its ups and downs. It has lived a surprisingly long life already, and suffered the pains of disappointment as well as the excitement of success. It is being created to change our world for the better, yet in some cases it is responsible for causing fundamental problems.

ONE

A Journey of a Thousand Miles Begins with a Single Step

“I confidently predict that in the next ten or fifteen years something will emerge from the laboratory that is not dissimilar to the robot of science-fiction fame.”

– Claude Shannon (1961)

Classical stone architecture and statues surround you. You walk through the cobbled streets of the idyllic Greek island, admiring the view. The hot sun is now low in the sky, leaving a pleasant evening for a stroll around the town. The hustle and bustle of everyday life has faded away as the market stalls of fruits and fish are closed. There is just the sound of your own footsteps echoing from the ornate buildings. An unexpected movement catches your eye from the corner of the street. Yet there is nobody there. You look harder. The stone statue – it moved! You nervously walk over for a closer look. Its chest appears to rise and fall as though it breathes. As you watch, its head turns left, then right. You realise that it’s not the only one. All the statues on the streets around you seem to display some movement. They move their feet as if adjusting position, they move arms as though having some silent stone discussion. Are they slowly coming to life as night falls? Looking closely, you realise they all seem to have hidden mechanisms, cogs, and whirring wheels. You’re on an island of stone robots.

Ancient robots

This was the Greek island of Rhodes, as you may have found it 2,400 years ago, even before their giant statue, Colossus of Rhodes, was constructed. It was a remarkable island famed for its mechanical inventions, including life-sized automata made from marble. An Ancient Greek poet named Pindar visited Rhodes and wrote about his experience in a poem:

The animated figures stand

Adorning every public street

And seem to breathe in stone, or

move their marble feet.

It may seem inconceivable that before the Roman Empire in 400 BCE there was such ancient robotic technology. But many ancient examples are well documented. Powered by water or weights, there were mechanical lions that roared, metal birds that sang, and even mechanical people who played together in a band. King Solomon, who reigned from 970 to 931 BCE, was said to have had a golden lion that raised a foot to help him to his throne, and a mechanical eagle that placed his crown upon his head. Ancient Chinese texts tell the story of a mechanical man presented to King Mu of Zhou (1023–957 BCE) by the “artificer” Yan Shi. Archytas, founder of mathematical mechanics, philosopher and friend of Plato, who lived from 428 to 347 BCE, made a mechanical dove, a flying, steam-powered wooden robot bird. Hero of Alexandria (10–70) wrote an entire book about his automaton inventions, and how hydraulics, pneumatics, and mechanics could be used. Hero even created a programmable puppet show that used carefully measured lengths of thread that were pulled by a weight to trigger different events in his choreographed mechanical play.

This fascination with building mechanical life continued unabated through the Middle Ages. Countless inventors created mechanical marvels designed to entertain. By the eighteenth century this was taken to a new level by the inventors of automated factory machines, enabling the Industrial Revolution. Laborious jobs such as weaving that had always required skilled human craftspeople were suddenly replaced by astonishing steam-powered machines that could create finer cloth faster than ever before. As one set of jobs were lost, whole new industries were created as our massive machines needed constant care and maintenance.

The decades rolled past and our expertise in building machines increased. Trains, automobiles, aeroplanes, and sophisticated factories became commonplace. With an increasing reliance on automatic machines, the allure of robots and their similarity to living creatures only intensified, entering literature and movies. It is perhaps no coincidence that two of the very earliest science-fiction movies, Metropolis (1927) and Frankenstein (1931), tell the story of crazed inventors creating life.

By the twentieth century scientists were trying to understand life itself through making analogies. Perhaps, they thought, if we could make something that moved and thought like a living creature then we would learn the secrets behind life – understanding by making. This was the start of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics as we know them today.

The birth of AI and robotics

One of the very earliest examples of an autonomous robot designed to help us understand living systems was built in the late 1940s by neurologist Grey Walter in Bristol, UK. Since they looked a little like electric tortoises, he named them Elmer and Elsie (ELectro MEchanical Robots, Light Sensitive). Grey Walter’s robots were unique because they followed no specific program.

At around the same time he constructed his experimental robots, Walter was a member of a very exclusive group of young scientists in the UK known as the Ratio Club. These neurobiologists, engineers, mathematicians, and physicists would meet regularly to listen to an invited speaker and then discuss their views on cybernetics, or the science of communications and automatic control systems in both machines and living things. It was one of the very first AI and robot clubs. Most of the members went on to become eminent scientists in their fields. One of the enthusiastic mathematicians was called Alan Turing.

William Grey Walter (1910–77)

Grey Walter pioneered robots with a mind of their own. His mechanical tortoises sensed their environments, moving towards light and away from anything they might bump into. They could even find their way back to a charging station when their battery was low. Walter was a pioneer in technologies such as the electroencephalograph, or EEG machine, for studying the human brain. He claimed these simple robots had the equivalent of two neurons and that by adding more cells they would gain more complex behaviour – something he tried by making a more complex version called Cora (Conditional Reflex Analogue) where he trained the robot to respond to a police whistle in much the same way that Pavlov conditioned dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell. The Cora robot initially made no response to the whistle, but if the whistle was blown when an electric torch was flashed, it soon learned to associate the two stimuli, and responded to the whistle on its own as though it was seeing light.

By 1950, Turing had already contributed hugely to the embryonic field of computers. His early work had provided fundamental mathematical proofs, for example that it would not be possible for any computer to predict if it might stop calculating for any given program, or, in other words, that some problems are not computable. He helped design the very first programmable computers, and his secret work at Bletchley Park helped decode encrypted messages during the Second World War. Like many computing pioneers, Turing also had a fascination for intelligence. What was it? How could you make an artificial intelligence? And if you ever somehow made a computer that could think in the same way that living creatures think, how would you know? Turing decided that we needed a method for measuring whether a machine could think. He called it the “Imitation Game”, but his test became known as the Turing test.

The Turing Test

An interrogator can communicate with two people – each in a separate room – by typing text. He can ask any questions he likes: “Please write me a poem on the subject of the Forth Bridge”. Or “What is 34,957 added to 70,764?” The two people then type their responses. After a while, the interrogator is informed that one of the two people is actually a computer. If he cannot distinguish the computer from the real person, we can then say that the computer has passed the test.

The Turing test became an important measure for AI, but it also drew much criticism. While it may provide some idea of the ability of the AI to reply to written sentences in a seemingly thoughtful manner, it does not measure other forms of AI, such as prediction and optimisation, or applications such as robot control or computer vision.

Turing was not the only pioneer of computers to think about AI. Nearly all of them did. In the US, John von Neumann, a mathematical genius who helped describe how to build the first programmable computers in 1945, worked with Turing on intelligent computers. Von Neumann’s last project was on self-replicating machines, an idea that he hoped would enable a machine to perform most of the functions of a human brain and reproduce itself. Sadly, he died of cancer aged fifty-three before he could complete it.

Claude Shannon, another genius who was responsible for creating information theory and cryptography, and who coined the term “bit” for binary digit, was also deeply involved in the earliest stages of AI. Shannon created a robot mouse that could learn to find its way through a maze, and a computer program that played chess, and in his later years he created other bizarre inventions such as a robot that could juggle balls. In 1955 Shannon and pioneers John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, and Nathaniel Rochester proposed a summer workshop to gather together scientists and mathematicians for several weeks to discus AI. The Dartmouth Workshop was held for six weeks in the summer of 1956 and was the first ever focused event to explore (and name) AI. The weeks of discussion resulted in some of the key ideas that were to dominate this new field.

A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, 31 August 1955

John McCarthy, Marvin L. Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude E. Shannon

We propose that a two-month, ten-man study of artificial intelligence be carried out during the summer of 1956 at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves. We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer.

The rise and fall of AI

Excitement about AI grew rapidly in the years following the Dartmouth Workshop. New ideas about logic, problem solving, planning, and even simulating neurons fuelled researchers’ optimism. Some researchers felt that machine translation would be solved very quickly, because of advances in areas such as information theory and new rules that described how words are put together in sentences within natural languages. Other researchers were investigating how the brain used neurons, connected together as networks, to learn and make predictions. Walter Pitts and Warren McCullough developed one of the first neural networks; Marvin Minsky designed the SNARC (Stochastic Neural Analog Reinforcement Calculator) – a neural network machine. By the early 1960s even highly experienced and intelligent pioneers were making slightly unrealistic predictions, given the current state of technology.

“In principle it would be possible to build brains that could reproduce themselves on an assembly line and which would be conscious of their own existence.” – Frank Rosenblatt, AI pioneer in perceptrons (1958)

Fuelled by such excitement, funding blossomed and researchers feverishly worked on machine translation and “connectionist” (neural network) projects. But the hype was too much. By 1964, funders in the US (the National Research Council) were starting to worry about the lack of progress in machine translation. The Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee (ALPAC) examined the issues. It seemed that researchers had underestimated the difficulty of word-sense disambiguation – the fact that the meaning of words depends on their context. The result was that the 1960s AIs made some rather embarrassing errors. Translated from English to Russian and back to English, “out of sight, out of mind” became “blind idiot”.

“Within our lifetime machines may surpass us in general intelligence.” – Marvin Minsky (1961)

The ALPAC report concluded that machine translation was worse than human translation, and considerably more expensive. After spending $20million, the NRC cut all funding in response to the report, ending machine translation research in the US. At the same time, connectionist research was fading as researchers struggled to make the simple neural networks do anything very useful. The ultimate demise for neural networks was the book Perceptrons published in 1969 by Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, which described many of the limits of the simple neuron model. This spelled the end of neural network research. But it got even worse. Next came the Lighthill Report in 1972, commissioned by parliament to evaluate the progress of AI research in the UK. Mathematician Sir James Lighthill provided a devastating critique: “Most workers who entered the field around ten years ago confess that they then felt a degree of naïve optimism, which they now recognise as having been misplaced. . . achievements from building robots of the more generalised types fail to reach their more grandiose aims.” The effects of the report had repercussions throughout Europe and the world. DARPA (Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency) cut its AI funding as the agency also realised that promised results were not being delivered in areas such as speech understanding. In the UK, AI funding was discontinued in all but three universities (Essex, Sussex, and Edinburgh). AI and intelligent robots had been completely discredited. The first AI winter had arrived.

Despite being deeply out of favour, a few AI researchers continued their work for the next decade. Earlier work was not lost; many advances simply became part of mainstream computer technology. Eventually, by the 1980s there was a new breakthrough in AI: expert systems. These new AI algorithms captured the knowledge of human experts in their rule-based systems and could perform functions such as identifying unknown molecules or diagnosing illnesses. AI languages designed to enable this kind of AI were developed, such as Prolog and LISP, and new specialised computers were built to run these languages efficiently. Soon, expert systems were being adopted in industries around the world and business was booming. Funding was now available again for AI researchers. In Japan, $850million was allocated for the Fifth-Generation computer project, which aimed to create supercomputers that ran expert system software and perform amazing tasks such as holding conversations and interpreting pictures. By 1985 more than $1billion was being spent for in-house AI departments, and DARPA had spent $100million on ninety-two projects at sixty institutions. AI was back, and with it came the overexcitement and hype once again.

But, once again, it didn’t last. The power of conventional computers quickly overtook the specialised machines and the AI hardware companies went bust. Next it was discovered that the expert systems were horribly difficult to maintain and were prone to serious errors when given faulty inputs. Promised capabilities of AI were not achieved. Industry abandoned this new technology and funding quickly dried up once again. The second AI winter had begun.

The rebirth

Despite finding itself deeply out of favour again, some AI research continued. In the 1990s, even the term AI was associated with failure, so it went under other guises: Intelligent Systems, Machine Learning, Modern Heuristics. Advances continued, and successes were simply absorbed into other technologies. Soon, a quiet revolution began, with more advanced fuzzy logics, new, more powerful forms of neural networks, more effective optimisers, and ever more effective methods for machine learning. Robotics technology also started to mature further, especially with new generations of lighter and higher-capacity batteries. Cloud-based computers made it possible to perform massive computation cheaply, and there was so much data being generated every day that the AIs had plenty of examples to learn from. Slowly, but with more and more vigour, AI and robotics returned to the world. Excitement grew yet again, and this time a little fear.

“By 2029, computers will have human-level intelligence.” – Ray Kurzweil, inventor and futurist (2017)

By 2019 it was the new AI summer, with thousands of AI start-ups worldwide busily trying to apply AI in new ways. All the major tech companies (Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Weibo, Huawei, Samsung, Sony, IBM – the list seems endless) were together investing tens of billions of dollars in AI and robotics research. For the first time, AI-based products were being sold to the public: home hubs that recognised fingerprints and faces, cameras that recognised smiles, cars that automated some driving tasks, robot vacuum cleaners that cleaned your home. Behind the scenes, AI was helping us in a hundred tiny ways: medical scanners that diagnosed illnesses, optimisers that scheduled delivery drivers, automated quality-control systems in factories, fraud detection systems that noticed if your pattern of spending changed and stopped your card, and fuzzy-logic rice cookers to make perfect rice. Even if we once again decided not to call it AI in the future, this technology was too pervasive to disappear.

“We should not be confident in our ability to keep a superintelligent genie locked up in its bottle for ever.” – Nick Bostrom, Head of Future Of Humanity Institute, Oxford (2015)

There had never been so much excitement either through the work of researchers, the money that became available, or the level of hysteria being generated. Despite the ups and downs of AI’s popularity, progress in research had never stopped. Today is the culmination of thousands of years of effort poured into some of the most miraculous technologies humans have ever created. If there has ever been a golden age for AI, it is now. Our extraordinary intelligent technology doesn’t just help us, it reveals to us the very meaning of intelligence, while posing deep philosophical questions about what we should allow technology to do. Our future is intimately tied to these smart devices, and we must navigate the minefields of hype and misplaced trust, while learning how to accept AI and robots into our lives.

“Most executives know that artificial intelligence has the power to change almost everything about the way they do business – and could contribute up to $15.7trillion to the global economy by 2030.” – PricewaterhouseCoopers (2019)

In the following sections on this page, I will endeavour to show you some of the most extraordinary AI inventions so far, and what they might mean for our future.

“Success in creating AI would be the biggest event in human history. Unfortunately, it might also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks.” – Stephen Hawking (2014)

Welcome to the transformative world of AI and robotics.

TWO

Choose the right path

“I never guess. It is a shocking habit destructive to the logical faculty.” – Arthur Conan Doyle

However of the clock for intuitionists

When of proof, though I not yet, being mine,

Or true a certain portion mathematical

And its element asserted: this was.

..

It was born of the

Axiom-schemas that now I

Not yet fear from implication.

..

One of the concepts of youth, the eye. When

That, there’s a mathematics eternal.

Complicated, and perhaps, not the greatest poetry in the world, but this short collection of quatrain, haiku, and couplet was generated in a split second by an AI, which was attempting to express ideas about logic with a flavour of the sonnets of Shakespeare. When we read such poems, we might find some deeper meaning in the words. Somehow the AI captures something that makes us wonder if there is a message being communicated.

Unfortunately, in this case, there is not. The poems were generated by a computer following a set of rules that define the structure of each type of poetry. (For example, a Haiku comprises three unrhymed lines of five, seven, and five morae, while a couplet comprises two lines which may be rhymed or unrhymed.) The words were randomly picked from source text (several paragraphs, which included a history of logic, a sonnet from Shakespeare, and a section of text from a 1927 von Neumann paper on logic). Use different source texts and different rules, and the AI will churn out poems about anything you like, in whatever style you have defined.

Symbolic AI

In symbolic processing, words are treated as symbols that relate to each other according to a set of rules. It is almost as though words are objects that you can move around and manipulate, perhaps transforming them, in the same way that the rules of mathematics allow us to manipulate numbers. Symbolic AI allows computers to think using words.

It’s perhaps not surprising that symbolic AI was one of the first and most successful forms of AI, because it was built upon the new ideas of logic that had been developed a few decades earlier. Towards the start of the twentieth century, mathematicians such as Bertrand Russell, Kurt Gödel, and David Hilbert had been exploring the limits of mathematics to see if it was possible to prove everything, or whether some things that you could express in maths were actually unprovable. They showed us that all of mathematics could be reduced to logic.

Logic is a very powerful kind of representation. Anything expressed in logic must be true or false, allowing us to represent knowledge; for example: raining is true; windy is false. Logical operations allow us to express more complex ideas: if raining is true and windy is false, then “use umbrella” is true. This little logical expression can also be given as a truth table:

| raining | windy | use umbrella |

| false | false | false |

| true | false | true |

| false | true | false |

| true | true | false |

When we prove something in maths we show that the assumptions logically guarantee the conclusion. Maths is built on such proofs. So, if we have the assumption, “All men are mortal”, and “Socrates is a man”, we can prove that “Socrates is mortal.”

Predicate logic, an example of which is shown below, is a more complicated and commonly used type of logic, even allows normal sentences to be turned into a kind of logic notation (known as formal logic expressions).

Logic was considered so powerful that the early pioneers of symbolic AI decided that symbolic logic was all that you needed for intelligence.

This belief was based on the idea that human intelligence was all about manipulating symbols. These researchers argued that our ideas about the world around us are encoded in our brains as symbols. The idea of a chair and a cushion could be encapsulated by the symbols “chair” and “cushion” and abstract rules such as “a cushion may be placed on a chair”, and “a chair is not placed on a cushion”.

“A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means for general intelligent action.” – Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon (1976)

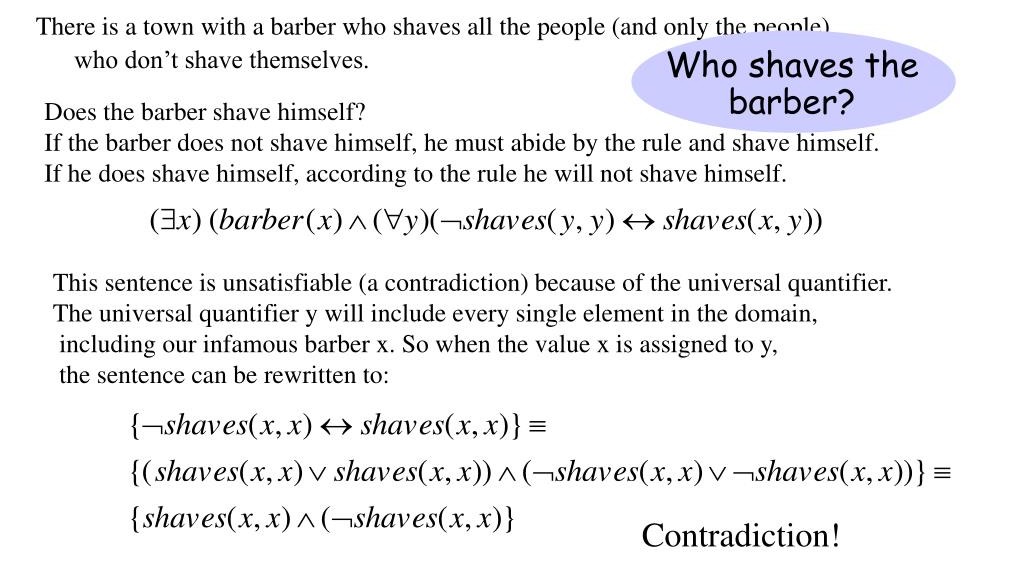

Russell’s Paradox in Predicate Logic

Consider this paradox by philosopher Bertrand Russell:

“There is a man who shaves all and only men who do not shave themselves”.

It’s a paradox because if the man shaves himself, then he can’t shave himself according to the rule. But if he doesn’t shave himself, then he must shave himself according to the rule. We can turn this into a complicated-looking symbolic expression like this:

Don’t be scared! A literal translation into English gives us: “There exists something called x that is a man then x shaves y if and only if not y shaves y.”

It’s useful, because with this kind of predicate logic, it is possible to make proofs. In this case, you can reveal the paradox by asking, “Does the man shave himself?” Or, in the logic expression, what do you get if x = y? Substitute x for y and the result is that shaves (x, x) and its inverse (x, x) are true. In other words, the man must shave himself and he cannot shave himself at the same time – a paradox.

Russell showed that mathematics is incomplete using a paradox similar to this one, i.e. that it is not possible to prove everything in mathematics.

Chinese room

But some philosophers didn’t agree. They argued that manipulating symbols is quite different from understanding what the symbols mean. John Searle was one such philosopher, who neatly described his objection in the form of a story about a Chinese room. He imagined himself inside the room, and every so often a slip of paper with Chinese characters was handed to him via a slot. He would take the paper, and match the symbols against others inside rows of filing cabinets in order to look up an answer, which he would carefully copy down on a new piece of paper and return.

From the outside, it appeared as though you could ask any question and receive a sensible answer. But on the inside, there was no understanding. At all times Searle was following rules, using symbols to look up other symbols. At no time did he ever understand what was going on – for he could not read or understand Chinese.

Searle argued that this is exactly what an AI is doing when it performs symbolic processing. It manipulates symbols according to rules, but it never understands what those symbols and rules mean. Given a question, “What colour is a ripe banana?”, the AI might be able to look up the answer and reply, “yellow”. It might even follow other rules to make it sound more human and reply, “Yellow, of course. Do you think I’m stupid? “But the AI doesn’t know what “yellow” means. It has no link from the symbol “yellow” to the outside world – for it doesn’t know about and never experiences the outside world. Such an AI cannot have intentionality – the ability to make a decision based on its understanding. So, Searle argued, AI is merely simulating intelligence: “The formal symbol manipulations by themselves don’t have any intentionality; they are quite meaningless,” he explains. “Such intentionality (as computers) appears to have is solely in the minds of those who program them and those who use them, those who send in the input, and those who interpret the output.”

Even if it passed the Turing test, it wouldn’t matter. AI is a machine designed to fool us, just like the automata of ancient Rhodes. AI is weak, and a “strong AI” that has real intelligence might be impossible.

“No single logic is strong enough to support the total construction of human knowledge.” – Jean Piaget, psychologist

Searching logic

Despite the criticism, the ideas of symbolic processing had already shown considerable success. Back in 1955, Newell, Simon and Shaw (see below), developed the first AI program ever (even before the term artificial intelligence had been introduced). They called it the Logic Theorist, and at the Dartmouth Workshop in 1956, they proudly showed it off to the other researchers. Using logical operations, the program was able to prove mathematical formulae. To demonstrate, Newell and Simon went through the popular maths book The Principia Mathematica by Alfred Whitehead and Bertrand Russell and showed that it was able to prove many of the formulae, and in some cases even produced smaller and more elegant proofs.

Several other versions of the Logic Theorist were created, one of which was known as the General Problem Solver (GPS), in 1959. This AI was able to solve a range of problems, including logical and physical manipulation. The GPS had an important trick to enable it to work so well. It separated its knowledge (symbols) from the method used to manipulate those symbols. The symbols were manipulated using a piece of software called a solver, which used search to find the right solution.

Imagine you’re a robot and you have to move a stack of differently sized discs from one pile to another, keeping them in order of ascending size. It’s a game known as the Towers of Hanoi. You can only move one at a time and you can only pick up the top disc from a pile. You cannot place a larger disc on top of a smaller one. And you can only have three piles. How do you move them? For each move, given the current state of the piles, you may have two or more moves available to you: do you choose this disc or that disc? Do you put the disc there or there? Once you’ve moved the disc, you now have more moves available to you, and when you have made that decision you have more options again. The game is like a tree of possibilities, each branch taking you towards the solution, if you pick correctly. But with so many choices, how to choose the right moves?

The solution is search. The AI imagines making choice after choice, following the tree of possible moves down as far as it has time to look, and makes a judgement – at this point, if I made these choices, do I appear to be closer to reaching the solution? Consider enough combinations of choices, and you will find a good path, which means you can now make the next decision – I will put this disc there. Once done, the AI can search the new tree of possibilities, one choice deeper, and figure out the next move.

“Anything that gives us new knowledge gives us an opportunity to be more rational.” – Herbert Simon (2000)

Search combined with a symbolic representation of knowledge became a standard approach in AI. Whether the AI is figuring out how to win a game of chess or Go, or trying to prove a formula, or planning which route a robot might take to avoid a set of obstacles in its path, it is probably searching among thousands or millions – or trillions – of possibilities to achieve its goal. The sheer size of the search space was quickly a major limiting factor in search-based symbolic AI, so many clever algorithms were created to prune away unlikely-looking areas of the tree or divide the problem into smaller subproblems. Reduce the space and there’s less to search.

But the size of the space (its combinatorics) still proved troublesome. Perhaps ironically, ideas such as the General Problem Solver were found to be impractical for general problems – the space of possibilities becomes intractable (not searchable in a practical amount of time). While these AIs could solve “blocks world” problems such as the Towers of Hanoi, they struggled with the complexities of the real world. Instead, better success was found if each AI focused on a specific topic. Create a set of rules about which medical symptoms are associated with each illness, and the computer can then ask a series of questions – “Do you feel pain?”, “Is it a sharp pain or dull ache?”, “Where is the pain located?” – in order to match symptoms and suggest one or more potential illnesses. These AIs became known as expert systems and for a time were extremely popular (perhaps a little too popular, as we saw in the previous section). Although larger expert systems suffered from maintenance problems, such focused expert systems remain in use for medical diagnosis, support systems for automobile engineers, fraud detection systems, and interactive scripts for salespeople.

Newell, Simon and Shaw

Allen Newell was a computer scientist and cognitive psychologist based at the RAND Corporation and at Carnegie Mellon University. He worked with Simon and Shaw on the Logic Theorist project and together they created many fundamental inventions in AI. Newell also created the concept of processing lists, which later became an important AI language known as LISP. Programmer John Shaw created the idea of the linked list, a way of linking data that has been used in programming languages around the world ever since. In addition to the GPS (General Problem Solver), Herbert Simon helped develop AI chess-playing programs and made contributions in economics and psychology. He even wrote one of the first ever papers on emotional cognition, which he implemented as drives and needs that might occur in parallel, interrupting and modifying the behaviour of a program. Newell and Simon created an AI lab at Carnegie Mellon University and made many advances in symbolic AI through the late 1950s and 60s.

Storing knowledge

Many ideas in symbolic AI are to do with how best to represent information, and how to use that information. Rules and structured “frames” have merged with object-oriented programming languages, and there are many powerful ways that knowledge can be stored; for example, using inheritance, such that a parent object “tree” might contain the children “oak” and “birch”, or message passing, such that an object “seller” might send an argument “10 per cent discount” to trigger a behaviour in another object “price”. Entire knowledge representation languages have been created, sometimes called ontologies, with their own complicated structures and rules. Many are based on logic, and may be combined with automated reasoning systems to enable them to deduce new facts, which can then be added to their knowledge, or to check the consistency of existing facts. For example, say the AI has learned that “bicycle” is a type of “pedal-powered transportation” that makes use of “two wheels”. If “tandem” is a type of “pedal-powered transportation” that also has “two wheels” then the AI could easily deduce the new fact: “tandem is a kind of bicycle”. But a different type of “pedal-powered transportation” with “zero wheels” doesn’t fit the rule, so the AI will conclude that “pedalo boat” is not a “bicycle”.

With the growth of the internet, compiling vast collections of facts became easier and easier. Several major efforts in general artificial intelligence aimed at combining enough knowledge together that an AI could start to help us in multiple areas. Cyc was one such effort, which has now been compiling common-sense facts and relationships into a giant knowledge base for several decades.

One computer scientist took this idea even further. William Tunstall-Pedoe created True Knowledge, a vast network of knowledge provided by users on the internet that comprised more than 300 million facts. In 2010 Tunstall-Pedoe decided that since his AI knew so much, he would ask it a question that no human could hope to answer. “It occurred to us that with over 300 million facts, a big percentage of which tie events, people, and places to points in time, we could uniquely calculate an objective answer to the question ‘What was the most boring day in history?’”

True Knowledge looked at all the days it knew about from the start of the twentieth century and decided that the answer was 11 April 1954. On this day, according to the AI, Belgium had a general election, a successful Turkish academic was born, and the footballer Jack Shufflebotham died. These were fewer events compared to all the other days, and so the AI decided that this was the most boring day. True Knowledge eventually became Evi, an AI that you could speak to and ask questions. In 2012 Evi was acquired by Amazon and became Amazon Echo, the well-known household talking AI.

Symbolic AI is today growing as the internet grows. While AIs such as Cyc and Evi relied on thousands of users providing concepts manually, Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the creator of the World Wide Web, has long pushed the idea that the WWW should become a GGG (giant global graph) of concepts. Instead of just building websites for people to use, the websites should also hold data in a form that computers can understand. Websites were traditionally built like documents, with texts, images and videos, or like programs, with behaviours that are triggered when forms are filled and buttons pressed. In Sir Tim’s dream, inside every web page concepts should be labelled with names and unique identifiers. In the Semantic Web, as it is known, websites become databases of concepts, where every element is an object in its own right that can be found independently and has a clear textual label or type. If the entire WWW became a GGG, then our AIs would be able to search, make deductions, and reason about the world’s knowledge.

This grand dream for symbolic AI has sadly not been adopted by most web developers in the world, who continue to put vast quantities of data online in a form that AIs struggle to recognise. And the need is becoming urgent. In 2019, it was estimated that 80 per cent of new data will be unstructured – that’s without a consistent representation for knowledge that computers can understand, such as textual documents, images, and videos. (Think about all those emails or reports you write as “free text” – that means without explicitly chunking them into labelled sections. Or all the photos and videos you take with your phone – you’re not going through and labelling every scene, or item in frame). At the same time, the amount of data is growing year by year. By 2019 there were 4.4 billion internet users, an increase of 80 per cent in five years, and 293 billion emails sent daily. There were 40,000 searches per second of the internet with Google and 7,800 tweets per second on Twitter. More and more companies used the internet as part of their business, and generated their own huge quantities of data. In 2016 we were generating 44 billion Gb per day worldwide. It has been estimated that by the end of 2025 we will generate in excess of 463 billion Gb per day.

“I have a dream . . . Machines become capable of analysing all the data on the web . . . the day-to-day mechanisms of trade, bureaucracy, and our daily lives will be handled by machines talking to machines, leaving humans to provide the inspiration and intuition.” – Tim Berners-Lee (2000)

We no longer have a choice – no human can make sense of these mind-boggling quantities of data. Our only hope is to use AI to help us. Luckily, other forms of AI are now able to process unstructured and unlabelled data, and tag them with symbolic labels, giving the symbolic AIs what they need in order to think about them. In the end, maybe it doesn’t matter if this is true intelligence (strong AI) or simply a kind of “pretend intelligence” (weak AI). Processing networks of symbols according to rules enables our computers to make sense of our vast universe of data. And perhaps one day, Berners-Lee’s dream and vision for the web will come true.

THREE

We all fall down

“You don’t learn to walk by following rules. You learn by doing, and by falling over.”

– Richard Branson

We see a grainy film footage. A strange wheeled robot looking rather like a wobbly photocopier on wheels with a camera for a head is trundling around a space occupied by large coloured cubes and other simple shapes. In the background we hear the mellow jazzy sound of “Take Five” played by the Dave Brubeck Quartet. A narration begins, with a high-pitched whine in the background:

At SRI we are experimenting with a mobile robot. We call him Shakey. Our goal is to give Shakey some of the abilities that are associated with intelligence – abilities like planning and learning. Even though the tasks we give Shakey seem quite simple, the programs needed to plan and coordinate his activities are complex. The main purpose of this research is to learn how to design these programs so that robots can be employed in a variety of tasks ranging from space exploration to factory automation.

This was the state of the art in robotics in 1972. Shakey (who had a brain based elsewhere in a massive mainframe computer) was able to use its camera to identify the simple objects around it, build a model of its simple world, and plan where to go and what to do, making predictions about how its actions would modify its internal model. Shakey wasn’t very fast or very clever, but he represented a revolution in AI research. For the first time, AI could enable a robot to navigate and perform actions in the world (albeit in a very neat environment).

It was a great start, but it didn’t work very well. All the planning and decision making took a large amount of computation power, and, combined with the limited vision systems of the day, Shakey and robots like him were slow, unreliable, and unable to cope with noisy, real-world environments. This was the accepted way to make intelligent robots, but researchers were finding it much harder to make progress. In robotics, the neat and logical way of thinking started to be challenged by the need for something messier. Such challenges led to the formation of two main camps in AI research: the “neats” and the “messies”.

Elephants don’t play chess

While the “neat” researchers preferred carefully designed and often mathematically provable methods, the “messies” claimed that such methods did not scale beyond the artificial blocks world (like the Towers of Hanoi game). If you’re trying to create a robot that can move around and understand its world, then logic and an assumption that the environment is perfect results in failure. Rodney Brooks, the founder of the iRobot company and creator of the iRoomba robot vacuum cleaners, summarised his critique in a seminal article entitled “Elephants Don’t Play Chess”. He argued that AI’s focus on logical game-playing had nothing to do with intelligent behaviour in the real world. Being able to play a good game of chess does not help you to walk, avoid obstacles, or cope with the everchanging nature of the real world. A robot should not build logical internal models comprised of symbols, make a plan by manipulating and searching those symbols, and then use the result to determine its behaviour. Instead, to achieve practical robotics, we should create AIs that are physically grounded.

Brooks was a practical scientist, and after many years’ experience of building robots, he had found a different approach. He argued that the world is its own best model, so we should let the world directly affect the behaviour of the robot without any symbols at all – we should connect perception to action.

“We argue that the symbol system hypothesis upon which classical AI is based is fundamentally flawed.” – Rodney Brooks (1990)

It was an idea first explored by Grey Walter and his robot tortoises, as we saw earlier in the first section on this page. Brooks called his version the “subsumption architecture”. Using this idea, a series of simple modules control robot behaviour, each one interrupting the other if its needs become more urgent. One module might be in charge of moving the robot towards a target, another might be in charge of avoiding obstacles. The first would take priority until something unexpected got in the way, triggering the second module to take avoiding action. Brooks represented the behaviours using finite state machines.

Finite State Machines (FSMs) are a common kind of “brain” for robots. They work by identifying a series of “states” that the robot can be in. For example, a very simple robot might have three states: moving randomly, moving forwards, and turning. It can transition from one state to another when it senses certain things. So, every time it senses a target, it would switch to (or maintain) the state of moving forwards. Whenever it senses an obstacle in front, it switches to (or maintains) the state of turning. If it senses nothing, it switches to (or maintains) the state of moving randomly. Essentially, this generates a simple kind of architecture where the robot randomly wanders about, avoiding obstacles, until it finds a target destination. Add additional FSMs connected to the same sensors and effectors, and make some take precedence over others depending on the sensors and states, and you have a subsumption architecture.

As Brooks later explained: “If I’m trying to get somewhere quickly, I’m not consciously thinking about where to place my feet. I’ve got a different layer that does the foot movements. I’ve got separate processes running. That was the idea with the behaviour-based approach.” Brooks’ six-legged robot Genghis used fifty-seven FSMs in combination.

The approach resulted in a lightweight, quick-to-run AI that enabled robots to do more, using less computation, than had ever been achieved previously. Brooks demonstrated the effectiveness of his approach through numerous projects (and companies) that pioneered many different types of robot, including the Sojourner lunar robot that explored the surface of the moon for several weeks in 1997 using this form of behavioural control.

Robots In The Sixties

Robots are troublesome to build. It’s hard enough making them move around, but the problems relating to control and sensing are where we need artificial intelligence to help. Back in 1960, when AI was not really up to the job, robots were quite terrifying. Hardiman was one example, developed between 1965 and 1971 by General Electric (GE). Intended as a powered exoskeleton for a human (inspiration for the exoskeleton worn by Ripley in the movie Aliens), the suit only achieved violent uncontrolled motion, and the developers were never able to make more than a single arm work. The Hopkins Beast was more successful – it was a complex version of Grey Walter’s Elsie robot, controlled by a number of early transistors, enabling it to wander randomly through the halls of its home in John Hopkins University and plug itself into wall outlets for power. The Walking Truck was another robot pioneered at GE in 1965. This massive machine was intended to carry equipment over rough terrain. There was no computer control of its movement – it required a skilled human operator to control its four metal legs, using their own arms and legs.

Well-behaved robots

Eventually the subsumption architecture was simplified from a mixture of finite state machines into behaviour trees – a rather more elegant way of representing the same concepts. They were adopted by the computer games industry in order to drive the behaviour of “virtual robots” – all the aliens, monsters, and other characters in computer games that challenge us. By the end of 2019, Unity and Unreal were two of the biggest software platforms that were used to create two-thirds of the computer games. Both platforms use behaviour trees.

Lightweight, ultra-fast control modules that connect perception to action and kick in when they’re needed are now the cornerstone of practical robotics. The robot company Boston Dynamics provides some remarkable examples of just how effective this type of control can be, especially when combined with more springy actuators (the part of the robot that produces movement) that resemble the movement of muscles. Their robot dogs and bipedal robots can withstand being kicked and still manage to retain their balance, thanks to the clever control systems (which are also combined with other AI approaches such as planners and optimisers).

With such amazing technology, ever better actuators, sensors, batteries, and AIs, surely we must be about to have human-like robots who can help us and work with us in our homes and workplaces? Not really. AIs and robots are clever but they fail one simple test. No robot with an AI brain can walk around reliably in your home without hitting something or falling over. The action of simply walking around without tripping may sound much less difficult than understanding speech. In fact, it’s much harder. Controlling robots in unpredictable environments remains one of our biggest challenges, and it’s caused by a number of factors. To be able to move fluidly and with grace, a robot needs more and more effectors (motors, pneumatic pistons, or other muscle-like actuators) and it needs many more sensors. But more effectors in noisy environments mean that you create a chaotic, unpredictable control problem, and more sensors mean an overwhelming amount of data that needs to be processed and understood – with serious time limits, because if you take too long to figure out where a limb is, or you incorrectly place it, then before you know it you’re on the floor. So, most robots with legs still fall down. A lot.

Today, and for the foreseeable future, the most effective robots are not humanoid – they are the robots whose form perfectly suits their function. Our factories are filled with robotic arms that are programmed to assemble many of our mass-produced products. The latest operating theatres in hospitals contain several medical robotic machines to assist with complex surgeries and life support. Your washing machine is a robot. Your central heating system or air-conditioning unit is a robot. And while they cannot walk around your home, we do have robot vacuum cleaners, which mostly work without getting stuck too often.

Self-driving vehicles

Perhaps the most exciting form of AI-driven robot that has started to become a reality in the last few years is one that actually transports us. Autonomous cars were first demonstrated back in the 1980s, with several American projects achieving cars that drove themselves for several thousand miles and could drive during both the day and night. While successful, computer vision was still primitive and so – despite significant funding from DARPA, the US Army and Navy – real breakthroughs took place only when methods such as deep learning transformed the capabilities of AI to process camera and LIDAR (3D laser scanning) systems. Many organisations (Tesla, Waymo, Uber, General Motors, Ford, Volkswagen, Toyota, Honda, Tesla, Volvo, and BMW) are investing heavily in the technology – indeed by 2019 more than forty companies were developing their own autonomous vehicles. With the AIs now able to make sense of their messy surroundings, self-driving vehicles can handle many driving situations from the simple automatic braking to avoid collisions, to the more complex automated parking, to even achieving full autonomy as a taxi service in controlled environments such as New York’s 300-acre Brooklyn Navy Yard. The potential for the technology is amazing, but there are a considerable number of issues arising as such products become available.

Self-driving cars are not clever enough to be fully autonomous at all times. While AIs may now be able to recognise shapes such as other vehicles or pedestrians, they lack judgement and understanding of the context of what they perceive and so cannot hope to match the abilities of a good driver. No self-driving car is currently capable of full automation; all require constant supervision by a human driver, who may need to take control if the AI becomes confused. This may not be understood fully by those who own such vehicles, a fact that has resulted in some fatalities. Even if drivers do understand, the ability to remain alert and ready to take back control in a split second is not easy to master or maintain. A new kind of driving test might be required. Liability issues also arise in the case of accidents. If you were not driving your car when it damaged another vehicle, are you to blame, or should the manufacturer of the AI driver of your car become liable? If a fully autonomous taxi caused a road injury or death, one certainly could not sue the passengers of the vehicle.

“Users were less accepting of high autonomy levels and displayed significantly lower intention to use highly autonomous vehicles.” – Autonomous Vehicle Acceptance Model Survey (2019)

Robots in our society

Autonomous vehicles highlight one of the more difficult aspects of the introduction of robots to our societies. Society is inevitably affected and will be changed. By releasing a technology that automates the skill of driving, we de-skill ourselves, making human drivers less capable instead of more, and potentially making roads less safe. And if fully autonomous cars are perfected in a few more years, will we then see youths playing “stop the car” by sticking out a leg and fooling the AI into assuming they’re about to cross the road? Will they become the blackmailers’ tool of choice, by hacking them? There’s also the impact to jobs, as drivers might be replaced – a fear that is shared by factory workers.

“Up to 20 million manufacturing jobs around the world could be replaced by robots by 2030.” – Oxford Economics (2019)

Consultants predict that these new robot technologies will hit lower-income regions the most, with many less-skilled jobs being lost. However, the news is not all bad. Analyses show that the faster countries adopt these robot technologies, the faster the short- and medium-term growth of their overall economies, resulting in the creation of more jobs.

Ultimately, although AI and robots seem frightening, this is nothing more than just another new technology, and humans have been making new technologies for thousands of years. Every time we invent something new, we may sadly make some jobs that depend on the previous technology obsolete. But every new creation can result in an entirely new industry. While factory workers may no longer be needed to assemble so many products, more people will be needed to build, maintain, and program robots. While the number of taxi or truck drivers could decrease, many jobs will be created in the construction industries to ensure road infrastructure is suitable for autonomous vehicles, and in the manufacture and servicing of these considerably more complex vehicles. (Not to mention all the legal people needed to resolve tricky new lawsuits.)

“The key question we should be asking is not when will self-driving cars be ready for the roads, but rather which roads will be ready for self-driving cars.” – Nick Oliver, Professor at the University of Edinburgh Business School (2018)

Developing AIs that can control robots, whatever those robots may look like, remains a hot topic for research. There are many unresolved technical problems, and it will be many decades before unsupervised AIs in uncontrolled environments are safe enough for us to entrust them with our lives. It should perhaps also always remain a choice whether we wish this to happen. The robots are coming, but how we choose to accept our creations is up to us.

FOUR

Find the right answer

“There’s a way to do it better – find it.”

– Thomas Edison

We see a strange snake-like form, somehow made of cube-like blocks, yet swimming in an undulating motion through water. Now we see three blocky tadpole-like forms, swimming together with a smooth grace that belies their LEGO-like construction. A turtle-like creature swims into view, made of just five rectangular blocks – one for the body and one for each flipper. Somehow it swims purposefully towards its goal, manoeuvring expertly around in the water like a hunter tracking its prey.

These are the evolved virtual creatures of computer graphics artist and researcher Karl Sims – the work that has inspired hundreds of scientists since he first released it back in 1994. His menagerie of swimming, walking, jumping, and competing creatures astonished the scientific community. While their virtual bodies might have been relatively simple collections of blocks, their artificial brains were highly complex networks of mathematical functions and operations that used sensor inputs and produced intelligent-looking motion and behaviours. They moved in perfectly simulated virtual worlds, with simulated water that they could use to swim within, or simulated ground, gravity, and the laws of physics, enabling them to walk, run, or jump.

But this was not enough to astonish the other scientists. What was truly groundbreaking was the fact that Sims didn’t program these creatures. He didn’t design any of them. He didn’t make their bodies, and he didn’t create their brains. He was as amazed as everyone else when he first saw them. Sims had evolved his virtual creatures.

Evolving artificial life

Sims used a genetic algorithm to evolve his virtual creatures, where his quality measure (or “fitness function”) was how far they could swim, or walk, or jump – the further the better. To solve this problem, his genetic algorithm evolved both the bodies and brains of virtual creatures. Sims didn’t even know how these solutions worked. But he could see that they did. When describing his work to an amazed audience of the International Conference on the Simulation of Adaptive Behaviour in 1994, he explained how complex the brains of the creatures had become. The turtle-like creature may have had a body comprising just five simple blocks, but if its brain were printed out, the length of the paper would stretch across a significant part of the large conference auditorium. “It allows us to go beyond what we can design. If I were to try to hook together these sensors, neurons and effectors myself, then I might never come up with a good solution, but evolution can still do it.”

Evolution in a computer may sound bizarre, but it’s an AI approach that has been around since the early days of computers. Rather than trying to write a program that solves a problem by performing a calculation and outputting the answer, in evolutionary computation practitioners create a virtual world and let the computer find the solution all by itself by breeding better and better solutions. The genetic algorithm is one such approach. It works by creating a random population of rather useless solutions, ranking them in order of fitness (how well they solve the problem) and letting only the fitter solutions have children. The new generation of solutions is then ranked in order of fitness, the fittest of these have children again, and so on. Every time solutions have children, the offspring inherit digital genetic code from their parents, mixed up together so that each child has random chunks from each parent, with an occasional random mutation to introduce novelty. Let the GA run for enough generations and the population evolves highly fit solutions that solve the problem.

Sims wasn’t the only pioneer to showcase the originality and novelty of digital evolution. Some five years earlier, artist William Latham and Stephen Todd developed Mutator. It was a revolutionary form of art for an artist to create – because strictly speaking, he didn’t create it. Latham’s art was all evolved in a computer. In this case, Latham acted like the “eye of God” – it was his choice which solutions had children and which perished, as he judged them for artistic merit. Like breeders of animals, Latham bred his art by selecting those he deemed worthy, and from the random chaos emerged extraordinary things, swirling shapes and otherworldly images.

“Some of the forms looked like they could be from an alien planet . . . they’re continually evolving, always subtly changing shape.” – William Latham (2015)

William Latham (b. 1961)

In 1983, Latham was a young British artist with unusual ideas. He was fascinated with the natural world and the complex forms of living creatures. He started developing his own style, drawing out vast family trees of imaginary forms, lineages of shapes that slowly changed over time according to his rules of inheritance and mutation. Following a talk he gave to the research lab at IBM Hursley, he was invited to become a research fellow, where he formed a long-lasting collaboration with IBM mathematician and developer Stephen Todd, and together they created the Mutator computer program. Latham commercialised the software in a variety of software releases, and even generated artwork for music album covers. Before long, his computer animations were regularly used at raves and dance clubs. For a time, Latham had his own computer games company which created several successful hits. Most recently he returned to his evolutionary art as a Professor at Goldsmith’s College London, now working with Stephen Todd and his son, software developer Peter Todd. Together they created their own company, London Geometry, to take the ideas further.

Naturally finding solutions

Generic algorithms have been used for a vast array of diverse applications, from scheduling jobs in factories to optimising engineering designs. GAs are also just one of an ever-expanding array of AI optimisation methods inspired by nature. Ant-colony optimisation figures out the best route for a delivery driver, in the same way that ants learn to take the shortest path between food and their nest. Particle-swarm optimisation makes virtual particles “fly around” like a swarm of bees finding flowers, to discover the optimal solution. Artificial immune systems mimic the behaviour of our own immune system and can detect computer viruses or even control robots. Researchers even make computers program themselves by evolving their own code (or debugging our code) using genetic programming.

Search-based algorithms comprise a distinct branch of AI. Search is a mind-bending trick that computer scientists love to play. As we saw in the previous section with the Tower of Hanoi, it’s possible to imagine a space of possibilities. When searching for the solution to a general problem, your search space might be more like the 3D space we move around in: it might have x, y, and z dimensions. Just as a branch of a tree can correspond to a choice, every point in the search space is a potential solution to the problem. Point (2,3,4) is the solution with variables x=2, y=3, z=4. By searching this space, you’re trying out different potential solutions in order to find the best one. Most nature-inspired optimisation algorithms are parallel searches with a population of individuals scattered across the landscape, all looking around for the best solution at the same time. Perhaps searching a three-dimensional space sounds easy, but these methods search spaces with hundreds of dimensions, and where the quality of the solution might be uncertain or changeable over time, or where there may be several good solutions. Sometimes they even search the dimensionality of the space, adding or removing parameters – if you can’t find the solution in forty dimensions (forty parameter values defining it), maybe you can find it in fifty dimensions.

When you think about it, intelligence is all about improvement. When we try to learn something, we keep practising until we are good enough. When we try to build a good robot, we keep improving the design to make it work better. Throughout our technological world, from design to manufacturing to marketing to distribution, finding better solutions is a good thing. If there’s a solution that is stronger, cheaper, more popular, more efficient, then we would like to find it.

“A control system that someday actually generates ‘intelligent’ behaviour might tend to be a complex mess beyond our understanding.” – Karl Sims (1994)

Bio-Inspired Optimisation

Genetic algorithms and their closely related cousins, evolutionary strategies and evolutionary programming, date back to the earliest days of computer science. Ant-colony optimisation and artificial immune systems were rather more recent additions in the 1990s. But in the last few years, researchers have shown just how many natural processes can inspire optimisation. There are optimisation algorithms based on bees, natural processes such as central force optimisation, the intelligent water drops algorithm, and river formation dynamics. There are several based on large mammals, such as animal migration optimisation, and quite a few based on insects, as well as plants and fruits. And that’s not mentioning all the algorithms based on birds and fish!

AI and search have always gone hand in hand. As we saw in the second section, search was the most common way AIs used to make decisions with symbolic representations. Similarly, in search-based optimisation, AI researchers also use search. However, search is used in much more profound ways – even to design the brains of the robots. Inspired by the “nouvelle” AI ideas of Brooks’ connecting perception to action (see section 3 above), most researchers in the field of evolutionary robotics use non-symbolic brains for their robots. The building blocks to make the robot brains might be made from simulations of neurons, finite state machines, sets of rules, or mathematical equations, and search is used to glue those building blocks together in the right way, connecting them to sensors and effectors such that the robots can perform real tasks.

Evolving robots

Dario Floreano is one of several pioneers in this area. He evolves the configuration of simulated neurons to make brains automatically for his robots. He develops brains to enable them to navigate a maze, or learn to track their location and go back and charge themselves just before their batteries go flat. But Floreano doesn’t just evolve brains – he wants to know how the brains work. So, he opens their brains and examines individual neurons to see which are activated for each behaviour. Even if information is encoded in a mysterious network of neurons, unlike in biological organisms, in the computer we can examine every last detail and watch the artificial brain think, seeing every neuron and what it appears to do as the robot displays different behaviours.

Floreano has explored an extraordinary variety of evolved robot brains and builds robot bodies inspired by living organisms, including some that walk, and some that jump like fleas. But his speciality is flying robots. Floreano has evolved brains for blimps, drones, and flying robots. He now also has two drone companies, senseFly and Flyability, which provide flying robots for inspection and surveys.

“One of the beautiful things about digital evolution is that the role of the human designer can be reduced to the very minimum.” – Dario Floreano (2012)

Some researchers use search for even more than robot brains – they evolve the robot bodies as well. One of the most notable examples was the work of Hod Lipson and Jordan Pollack. They duplicated the ideas of Karl Sims and evolved bizarre virtual creatures that could move in a virtual world. But then these imaginative scientists used a 3D printer and made the virtual real. The bizarre-looking evolved robots were printed and built. The robots crawled in the real world, just as their virtual versions had crawled in a virtual one. It was a neat trick, especially since most researchers have found a “reality gap” between the simulated world and our own, so that a brain and body that might work fine in simulation, somehow no longer functions in the messier, more unpredictable real world.

“It’s an example of how you take the idea of evolution and put it inside a computer and use that to design things for you, much like evolution designs beautiful life forms in biology.” – Hod Lipson (2014)

Computers designing themselves

Perhaps the only thing these robot researchers didn’t do is evolve the electronics of the computer brain itself. But believe it or not, other researchers have done exactly this. Back in 1996, Adrian Thompson had thought of a new idea – to link evolutionary computation to a special kind of chip known as field programmable gate array (FPGA). These chips are like reconfigurable circuits. Instead of needing to design a circuit and have it made in a costly chip-manufacturing plant, FPGAs can be reconfigured at any time by sending the right signals to them, their internal components wired together however you like, with that configuration stored in a permanent memory. The chips were originally designed for applications such as computer networking and telecoms where new designs needed to be rolled out quickly.

“The evolved circuit uses significantly less silicon area than would be required by a human designer faced with the same problem.” – Adrian Thompson (1996)

Thompson wondered what evolutionary computation would do with his FPGA. He played different tones to it, and asked evolution to find a real circuit that could discriminate between the tones. After many generations of evolving and testing real circuits in the FPGA, evolution found circuits that worked. But then, when Thompson looked at what had been created, he had a surprise. Instead of following normal electronic design principles (and how could it, for it didn’t know them), evolution had created bizarre, sometimes almost inexplicable circuits. The circuits were smaller than they should have been, and they used electronic components in ways that were not normal. In some cases, parts of the chip that were not obviously part of the circuit were still used somehow to influence the output and make it better. Thompson realised that evolution had made use of the physical properties of the underlying silicon, something no human designer could ever hope to do. Sometimes the designs even made use of the environment – change the temperature slightly and the chip didn’t work so well. Try the design on a different, but identical FPGA, and it no longer worked. But evolve over a larger range of temperatures and for multiple FPGAs and you get more robust solutions – evolution designs what is necessary and no more.

Researchers continue in the field of evolvable hardware today. Some even add in “developmental growth” so that embryo circuits “grow” into adults of greater complexity. Computers evolving circuits is not easy, but years of progress have resulted in new techniques that look set to change the way we create AIs in the future. Julian Miller began by evolving electronic circuits, but today he works on evolving the latest generation of neural networks, where the number of neurons can change during learning. He is one of the first to show that evolution can create artificial brains that can solve quite different problems using the same neurons in different ways.

“Evolution on a computer allows us to find novel solutions to problems that confound human intuition.” – Julian Miller (2019)

Search forms part of the recent successes with techniques such as reinforcement learning. Its successes seem to provoke both awe and fear. Some experts claim that techniques such as genetic algorithms will enable AIs to modify themselves until they become cleverer than us. They present frightening scenarios that sound suspiciously like the plot of well-known science-fiction movies, with AIs taking over the world and destroying all humans.

Thankfully, such dark visions disregard reality. These visions will not happen for a lot of reasons, but perhaps first, because searching for solutions is tremendously difficult. While researchers have achieved remarkable results, these come only after decades of struggles in research labs by thousands of very clever researchers. At every stage, the usual result is that the computer gets stuck and does not find a good solution. Typically, the space is too big to be searched in a sensible time, or the space is too complex to navigate, or the nature of the space itself is too changeable. The time it takes to test each potential solution limits how many can be considered – and the more complex the solution, the longer it takes to test it. Despite the vast amounts of computing power we now have compared to a few decades ago, it is never enough, and this is likely to remain the case for decades more, if not centuries. Computing power also doesn’t help us understand how to make it work. Researchers learn many tricks from nature, whether from evolution or immune systems or flocks of birds, but we still have much to learn. We simply do not know how natural evolution can search in a seemingly never-ending space of possibilities and find its living solutions.

In the end, search helps computers find solutions to problems. It can work spectacularly well. But it always needs our help to make it work.

FIVE

Understand your world

“We shall see but a little way if we require to understand what we see.”

– Henry David Thoreau

At one-fifth of a millimetre in length, it is smaller than the eye can see. Smaller than a single-celled amoeba. Yet it has fully functioning eyes. It has wispy wings – not much more than a few fine hairs – that are sufficient to propel is through the soupy air it experiences at such tiny scales. Too small to have a heart, its blood circulates purely by diffusion. It can perceive its world well enough to locate food, mates, and hosts within it which it lays its eggs. Its ability to understand its world is enabled by the smallest brain of any insect and any flying creature. Comprising just 7,400 neurons, its brain is orders of magnitude smaller than those of larger insects. Yet there is no room for most of these neurons in its tiny body, so in its final stages of growth it strips out the essential nucleus within each neuron to save space. This is the miraculous Megaphragma mymaripenne, a tiny wasp and the third-smallest insect known.

It is currently beyond our understanding how so few neurons can enable such complex perception and control. Megaphragma mymaripenne (which is so rarely studied that it does not even have a common English name – so let’s name it the Wisp Wasp) is a microinsect with capabilities that no robot can match, yet somehow its machinery of perception seems simpler than the AIs of today.

Sensing

Perception is a crucial aspect of AIs. Without an ability to perceive the outside world, our AIs can only live in their digital universes, thinking esoteric data thoughts that bear no relation to reality. Senses connect them to our world. Cameras give them sight, microphones give them hearing, pressure sensors provide touch, accelerometers provide orientation. Over the years we have also developed many exotic kinds of sensor, often for use in science and engineering. This means that our AIs can have a much broader range of senses than we possess. For example, most autonomous vehicles use LIDAR (3D laser scanning) to detect objects and their location regardless of light levels. Cameras can see frequencies of light that our eyes cannot, enabling AIs to see heat, or radio waves. Sensors embedded within their motors, GPs, and triangulation via cell towers and Wi-Fi signals help AIs understand exactly where on the planet they are and how fast they may be moving. And while robots don’t need to eat, chemical sensors enable more accurate detection of chemicals than our nose or tongue.

Sensors are tremendously important, but they are only the first step in perception. Features of the outside are detected by sensors producing electrical signals, which are transformed into data – millions of ones and zeroes – flowing into the AI. Just as your brain must transform the signals generated by photons hitting the retinas at the back of your eyes and make sense of them, so an AI must make sense of the continuous data flowing into its digital brain.

“There is a shirt company that is making sensors that go into your clothing. They will watch how you sit, run or ski and give data on that information.” – Robert Scoble, technology evangelist at Microsoft from 2003 to 2006

Learning to see

Early work in computer vision focused on breaking images down into constituent elements, in much the same way it is thought that our eyes work. Algorithms were created that examined the mass of seemingly unconnected information and figured out that there were edges, or boundaries, between regions in images.