– Mindfulness can be described in many ways. It is a practice of purposefully paying attention to the present moment and bringing a non-judgemental, compassionate awareness to the nature of things. It is a way of being, a way of relating to our inner and outer experiences, and a coming to our senses, literally and figuratively.

At the same time, it is nothing at all, nothing but a rediscovery or a remembering of our natural, inborn capacity to be fully awake in our lives, in contact with things in a direct way without the filters of concepts, past experiences, or likes and dislikes.

Above all, mindfulness is a path of the heart – a practice of loving awareness – that offers to hold any and all experiences in a compassionate, spacious embrace.

(1) DISCOVERING MINDFULNESS

Mindfulness is a universal, modern way to enhance life. Its practice can make us calmer and more centred and help to improve our physical wellbeing.

The idea of mindfulness is very simple: you pay close attention to an experience in the present moment, while allowing yourself to be open-hearted and “spacious”. This last word needs a little explanation. Our pure state of mind is spacious, but over time, as we accumulate life experiences, certain habits of thinking form and solidify. Mindfulness meditation, practised over a period of at least a few weeks, can break down these inner structures and return us to our original openness. That’s why mindfulness practice has been proven effective as an antidote to all kinds of negative mindsets, including poor self-esteem, high anxiety, low levels of vitality and engagement, and mild to moderate depression.

Mindfulness changes your sense of who you are in relation to your own life and to other people. It also gives you better access to your full potential, particularly in terms of relationships and personal goals. To live more mindfully is to live more richly, with more skill, ease, and flexibility. You gain in self-understanding and can use that as the foundation-stone for a happier life. When challenges occur or you encounter threats in life, you’ll be less likely to find them overwhelming; and when opportunities arise, you’ll be able to recognise them and welcome them joyfully into your life. Habits of mind will remain but exert less of a tug, giving you freedom to cultivate healthier ways of thinking.

Introducing the present

The main ingredient in the mindfulness recipe is the present moment. It isn’t that you need to concentrate on the moment itself, since a moment is impossible to pin down. Instead, what you do is focus on your experience in the present, forgetting about past and future, or time itself passing – as well as about any thoughts or emotions that enter your mind. You might be focusing on something you’re doing, or looking at, or listening to, or feeling as a sensation, such as your breath: you’re being mindful if you concentrate on this with relaxed but purposeful attention.

Mindfulness is not a state of mystical bliss or spiritual transcendence. It has no religious dimension.

Mindfulness is:

. Recognising feelings without being caught up in them

. Identifying yourself as who you truly are – and not identifying yourself with your feelings or mistakes

. Living more in the moment and less in the past and future

. A way to cultivate happiness that’s suitable for all.

Mindfulness is not:

. Emptying the mind or stopping thinking

. A relaxation technique, though it will make you more relaxed as a by-product

. An escape from personality – it reveals to us our personality

. A charter for living life without planning – you can plan in a mindful way, just as you can learn mindfully from the past.

The Benefits of Mindfulness

Listing the benefits of mindfulness feels rather like quantifying the value of love: its worth is intrinsic to itself, so trying to tease it into separate strands is missing the point. However, mindfulness has been much researched, and a checklist of its proven benefits is always useful as a motivating call.

The pioneer of modern mindfulness, Jon Kabat-Zinn, wrote rather disarmingly that you don’t have to like mindfulness practice, you just have to do it. He knew that some people found mindfulness a chore, but he was also aware of its tangible benefits. His early work is now supported by numerous scientific studies which shows that the practice of mindfulness enhances mental and physical wellbeing. Research highlights its success in reducing stress and anxiety, attributing this to a reduction in levels of cortisol – sometimes called the “stress hormone” – in the body. And since stress tends to undermine the effectiveness of the body’s natural immune system, mindfulness can also be linked with improved immunity.

The health benefits of mindfulness are undeniable. They range from stress and pain relief and improved sleep patterns to a greater likelihood of breaking out of depression or addiction. Beyond the province of health, though, is the vast realm of wellbeing, where the advantages of mindfulness practice multiply dizzyingly. In making us more attentive, more grounded, more self-aware, more confident, more decisive, and less bound to the habits of the mind’s autopilot, mindfulness opens up for us a new way of living. We learn to deal more effectively with life’s pitfalls and setbacks, but also to derive more satisfaction and enjoyment from life’s pleasures. No longer held back by negative patterns of thought about ourselves, we set ourselves on the path to releasing our full potential.

How mindfulness minimises pain

Some of the health benefits of mindfulness result from the way in which it trains us to be less reactive – for example, to our emotions. Pain, like an emotion, tends to draw us into itself to do battle with it. In seeking to block out a pain, we might clench our muscles in that part of the body, or we might engage in combat with the pain, sometimes angrily. These reactions drain us of energy without relieving the discomfort. The mindful way is to accept the pain and separate out the emotional reaction it causes. No longer reinforced by emotion, the pain becomes weaker.

Mind Full of Thoughts

Mindfulness is about directing our attention inwards, in the present moment, and making discoveries about what sensations we’re feeling, and what thoughts and emotions we’re having. When distractions occur – such as a memory surfacing – we just let them go.

The mind is an instrument, but also an inner landscape. However intently we try to concentrate our minds on a task, some thoughts will come straying into our inner field of view from time to time, distracting us from our focus. We have a choice: we can react to them, or we can take a more mindful route – we can simply notice them, without judgement, staying in the present moment as we do so.

Our thoughts and our direct experiences, though separate, are engaged in a perpetual interaction. While the human mind seems to be the ultimate multitasker, it can in fact only hold one thought at a time. It gives the impression of multitasking by performing the most incredible juggling act: from one moment to the next, some thoughts rise while others fall, to resurface later. But within this confusion, certain traceable lines of thought, or sequences of sensation and thought, will be operating, and these often originate in direct experience.

Choosing your focus

In mindfulness practice you choose where to place your focus. You direct your attention there, but you don’t worry if distracting thoughts or feelings, or perhaps unexpected sensations (like a clock chiming or phone ringing), cross your inner landscape. You note such unbidden experiences but exercise your choice not to engage with them. Instead, you redirect your attention to the matter in hand – your chosen focus – whether it’s your breath, a body sensation, or something else entirely.

Ripples of thought

The way our minds process sensations, thoughts, and emotions can be compared to a raindrop falling onto a pond. Direct experience – our sensations or emotions – are where the droplet hits the pond. The inner circle of ripples represents our initial thoughts, while the outer circles are the thoughts that develop from there. Thoughts tend to carry on generating further thoughts unless we direct our attention somewhere else. Mindfulness practice gives us the means to do this in our everyday lives.

Silent Witness

Mindfulness involves paying attention with a focused mind, in the present moment, without judgement. But what does this really mean? And why should the question of judgement arise when we’re focusing, say, on our breath or our bodily sensations?

Imagine that you’re meditating mindfully, concentrating your attention on your breath as it enters and leaves the body. Sitting down, you now direct your thoughts to the pressure of the edge of the chair against your lower thigh. That pressure is there every time you sit on the chair to eat your supper or write a letter, but you usually don’t even notice it, or attend to it at all. Bringing such sensations into the spotlight of consciousness – and keeping them there – is an example of paying attention with a focused mind in the present moment.

Very few of us can completely control our thinking. That’s because our minds tend to wander. So as you sit, mindfully focusing on the sensations in your thigh, you’re likely to experience distractions. Some will be prompted by external events, such as the chiming of a distant clock or the sound of the postman opening your gate; others will come out of your preoccupations.

Stopping short of judgement

Fragments of thought or emotion will emerge unbidden from the kaleidoscope of your unconscious. Often, they will be trivia – thoughts about where you left the scissors; sometimes they will be vague anxieties that you can’t quite pin down; and at other times they will be more troubling emotions, such as anger or fear.

Sometimes thoughts will visit alone, but often they’ll be accompanied by emotions. If you say to yourself, “I really don’t want this thought or emotion in my head now, it’s spoiling my mindfulness practice”, you’re making a judgement – an unspoken comment. In mindfulness, you’re not supposed to make such judgements on intruding thoughts or feelings, so what should you do with them? The answer is that you register your awareness of them, and notice exactly how you experience them, but you consciously refocus your awareness on your physical sensations – your breathing or the sensation in your thigh. You don’t engage with the thoughts or feelings, but by simply acknowledging them without judgement will see them fade away. This is mindfulness in action.

The power of autopilot

Autopilot is the opposite of mindfulness: it’s a state of mind disengaged from the present and stuck in habits formed long ago. Letting go of our automatic behaviour enables us to escape the pull of the past – and offers us a better chance of happiness.

Autopilot allows us to carry out basic functions in life – dressing, walking, climbing stairs – without taking up all our attention. It helps us to learn complex new skills, such as driving a car or touch-typing. Once we apply ourselves to learning, the skills start to become automatic – for example, you drive to a destination remembering almost nothing about your journey. This is often desirable because it frees the mind to move on to other things that require conscious attention.

However, autopilot can also work against us, particularly in the way we process our emotional lives. We often reflect on how we felt, or feel, about past experiences, and try to apply our conclusions to attain happier outcomes in the future. The problem occurs when we repeat this process automatically, offering the same emotional reactions to similar situations, even though the outcome last time was far from ideal.

Dissolving negative patterns

When on autopilot, the mind steals its reactions from the past. We don’t realise, when we are in auto mode, that we have a wide range of options available. The truth is, there’s no need to be hurt by a situation just because it’s hurt us before.

Consciously setting out to break established patterns by taking determined action is not necessarily the best way to overcome them: paradoxically, the patterns may be strengthened by such active resistance. What’s needed is a new, more mindful, way of thinking. By training ourselves to live in the present moment – and relate to our experience with acceptance rather than judgement – we become more grounded and more nimble in our responses. Autopilot dissolves when mindfulness takes over at the wheel.

| THE AUTOPILOT WAY | THE MINDFUL WAY |

| We react with habit | We respond with awareness |

| We emptily re-live the past | We fully live the present |

| We neglect realities | We accept realities |

| We miss the details | We notice the details |

| We re-enact established patterns | We see the big picture |

| We have limited choices | We have many choices |

| We repeat past emotions | We have fresh emotions |

| We neglect our potential | We realise our potential |

| We enjoy life’s pleasures less | We enjoy life’s pleasures more |

Five small ways to turn off auto:

Dissolving the habitual responses of your emotional life through mindfulness will take a great deal of effort and practice, but, for the moment, here are five ways to refresh your everyday routines:

[1] Leave your mobile phone at home – This may feel unsettling, since we’re all used to the sense of constant connection. Carrying our mobile devices, we’re never truly solitary. Rediscover what it feels like.

[2] Talk to a stranger – Spend a few minutes having a chat with someone you meet while shopping or travelling. Autopilot can undermine our sense of connection, except to friends, family, and colleagues. It’s good to realise that others may have something to offer.

[3] Do something new with your partner – Take your loved one to a kind of event you’ve never tried together before – anything from a hiking trip to a football match. Relationships can get stuck in routines. A novelty like this can jolt you out of your habits and reawaken your bond.

[4] Break a regular journey – Stop en-route and explore a new area before continuing. Start out earlier if necessary. Walk around observantly. Try to find something you can take from the experience: perhaps a shop you might visit again or the colour scheme of a house.

[5] Do that big chore – It’s autopilot that makes us procrastinate, avoiding uncomfortable experiences for as long as possible. Since it must be done, schedule a time as soon as possible. Don’t let it hang over you threateningly. Do it with your full attention.

A thousand leaves

Finding the moment in repetitive chores

British crime writer Agathe Christie famously said that the best time to plan a book is while you’re washing the dishes. It’s easy to see where she was coming from. The word “mindless” readily attaches itself to everyday chores, so if you can disengage from a boring and repetitive task and do it perfectly well on autopilot, then why not? You’ll get the dishes clean at the same time as sorting out problems that require your conscious attention.

Why then, would you wish to make a mindless task mindful? It’s bad enough sweeping the yard without having to inhabit every moment of the chore as if it were precious. The moments would be precious, you might say, if you didn’t have to spend them brushing leaves away, and trying to enjoy it.

Over and over

This parody of a popular, uninformed view is worth taking seriously for the questions it raises. Would you really miss a valuable experience if you did some thinking while sweeping the leaves? Wouldn’t you get the boring task done better and more quickly by tackling it head on, without mindfulness? And once you’ve swept a thousand leaves, would sweeping another few hundred really make the experience any richer?

Anyone who’s experienced the value of mindfulness should be able to tackle these questions without difficulty, since their intuition will be attuned to how it operates. First, they’ll know that mindfulness is not prescriptive. If someone has a menu to devise in their heads or a speech to plan, there’s no reason at all why they shouldn’t work on this while leaf-sweeping – especially if they’ve found they can think more effectively in such circumstances. Any feeling of guilt about this choice would be unnecessary. Mindfulness does not impose choices upon you in the way that your nagging, logical mind may do.

Thought and distraction

There’s a big difference, however, between consciously using the sweeping time for thought and going out there with no intention other than to get the job done. People doing a routine activity often drift into thoughts of planning, and find themselves repeating the same thoughts unhelpfully – until thinking becomes as automated as sweeping. Also, their mind is likely to stray into pointless worrying. In any case, if you take your mind off a repetitive job, you’re likely to do it more slowly and less efficiently.

Nobody is going to concentrate 100 per cent on leaf-sweeping, but if you do opt to sweep in the moment, with purposeful attention, and without judgement (not thinking “This is so boring”), you will create a stable place for your thoughts to settle. If they wander, and you start worrying about something, the mindful way is to observe those worries without getting drawn into them, and then gently, if you choose to, bring your focus back to your brushing. By the end of the session, you’ll have enjoyed a different kind of double benefit – getting the job done and spending some healing time (it is healing, though you won’t know this yet) in the now.

Bringing mindfulness to a routine task gives you the opportunity to be present in the moment, in a way that, over time, will help to rebalance your mind, bringing many of the benefits described above. Mindfulness in the long term will perform a gradual makeover on your brain.

Mindfully sweeping leaves isn’t just about getting to know what they really look like or subjecting yourself to a session of mental austerity – your mind is sure to wander and you can learn a lot from its unauthorised detours.

Mindfulness and happiness

Happiness was one thought to be a personality trait; you might have a happy, sunny disposition or a sad dark one. However, recent studies by behavioural psychologists show that it is far from a fixed trait and that it can be closely linked with mindfulness.

It is commonplace that money can’t buy you happiness. You could say the same about pleasure, too. Many people whose primary goals are wealth, physical thrills, or sensual excitement, eventually become jaded and listless. When you’re on the hedonistic treadmill, what you think will make you happy one day never quite does; soon you’re into the next thing, and then the next, in a fruitless search for satisfaction.

Mindfulness, despite the high value it places on the moment, is no cousin of live-for-today-forget-tomorrow pleasure-seeking. The contribution it makes is to establish a particular relationship with the present moment; this can bring happiness.

Love and friendship

If materialism and pleasure point away from happiness rather than towards it, which way should we travel hopefully? Many people would say that love is their biggest commitment – not a new, romantic kind of love, whose chemistry includes passion and anxiety, but rather the settled kind of love we enjoy with a long-term partner, our family, and our friends. Mindfulness, by opening our awareness to the people most precious to us, and encouraging us to understand and express our feelings for them, offers fertile ground for the growth of love. It also offers a form of mindful meditation called loving kindness practice, which extends the scope of the heart’s remit beyond the narrow circle of our intimates, to people in general, supporting the idea that giving brings rewards to us all.

Purpose and gratitude

People questioned about happiness often speak about purpose – how contentment comes from knowing that they are doing, or at least trying to do, something worthwhile. Mindfulness practice helps you to recognise your true purpose as part of its general enlargement of self-understanding; it also helps you to achieve your goals by sharpening your concentration and decision-making and building your self-confidence.

Gratitude for what you have is also conducive to happiness, and mindfulness encourages this by exploding the appeal of delusional priorities, such as status, and making you more intensely aware of the gifts of friendship, beauty, and the other riches of your life. Acceptance of what can’t be changed is another mindful quality that boosts our sense of wellbeing.

Happiness under pressure

Everyone finds that their resilience is tested from time to time by misfortune or the consequences of their own mistakes. However, mindfulness promotes resilience because the happiness that it nourishes is not easily compromised. There’s often a core of contentment beneath the troubled surface of life’s challenges: mindfulness helps you discover it.

Turn left for happiness

In the early 21st century, Dr Richard Davidson of the University pf Wisconsin, USA, correlated electrical activity in specific parts of the brain with reported feelings of happiness. His discovery was that positive feelings are accompanied by extra activity in the left prefrontal cortex, and negative feelings in the right prefrontal cortex.

The ratio between the two measurements was described as the “mood index”. Subsequent work by Dr Davidson and Jon Kabat-Zinn of the University of Massachusetts Medical School, USA, demonstrated that in people who’d undertaken mindfulness training, the readings shifted more to the left. Mindfulness, to put it in unscientific terms, “massages” the brain to be positive about life.

Outgoing happiness

These words – not arranged in any particular order – make up a prompt list, of active ways to bring happiness into your life by involving yourself givingly and mindfully with others:

Share – Listen – Amuse – Approve – Recommend – Cherish – Connect – Unburden – Play – Love – Ease – Liberate – Reassure – Support – Witness

Growing yourself

Mindfulness and your potential

People feel happy when they realise their potential to live as fully and contentedly as circumstances allow. We’ve already seen (above) how mindfulness can contribute to this. This section gives some further thoughts about breaking down the walls that can block your potential, then choosing your own direction for fulfilment.

Various self-help programmes set out to provide tools through which you can realise your potential. They may, for example, encourage you to experiment with new interests or to voice affirmations about your good qualities. Mindfulness is not averse to such techniques but takes a more coherent approach to self-realisation. When you practise mindfulness, you use meditation to shed any negativity in your self-image, replacing that with self-awareness and self-compassion; you then go on to make conscious choices in the light of your priorities.

Inner voices

Sometimes we may fail to realise our full potential because we have an excess of self-belief; being over-optimistic about success in a competitive field almost inevitably leads to disappointment. However, we are far more likely to suffer from the opposite delusion – failing to believe enough in ourselves. Negative voices in our heads repeat themselves: “I can’t, I can’t, I can’t”. With mindful attention we can be aware of these habitual patterns of thinking and choose, instead, to focus our minds on the authentic reality of present experience. Self-criticism will only hold us back if we engage with it, so we should learn to ignore the voices in our heads, unless they are motivating affirmations we deliberately place there.

Everyday potential

It is easy to get confused about what self-realisation really means. It is not the same as achievement, which has overtones of making a public impression – of gaining acclaim or respect among our peers. For example, in weighing up whether to sacrifice their careers for motherhood, many women imagine the domestic sphere to be inferior to the professional. In fact, of course, it’s down to personal priorities: for anyone who chooses to be a full-time mother, that course automatically becomes superior.

If we become confused about the meaning of self-realisation, mindfulness can clarify our true priorities and prevent our feeling guilty about rejecting other options. It can also help us detach ourselves from other peoples’ opinions, which are often either too negative or too flattering.

Looking off-centre

One of the questions that arises when we consider how to fulfil our potential is where to concentrate our efforts. Should we build strengths or correct weaknesses? The answer needs to come from self-understanding: are we really as clumsy at communication as we feel ourselves to be? Do we really have the aptitude and staying power to re-train in a new profession? Intuition and awareness are key, steering us away from the “funnel effect”: the idea that if we’re working to make progress in one area, we needn’t spare any energy to work on other issues. Beware of single-mindedness: mindful self-observation scans the whole field of view.

Self-realisation preview

To release your true potential, the best course of action is to follow a schedule of mindfulness meditations. The following ideas, expressed as “me” -statements, offer a short preview of what you can expect to believe more confidently as your training progresses:

. I’m entirely myself, not the sum of what other people think about me

. I choose my own priorities in light of all relevant factors

. I choose my own goals and my criteria for success in reaching those goals

. I’m wary of my expectations but I am fully committed to my intentions

. I know my feelings and choose which ones to act upon

. I change my priorities and my goals when my circumstances change

. I accept what happens to me, without frustration.

Constructive dialogues

The way you express your inner dialogues can build barriers that prevent you from realising your potential.

Beware of “Can I see myself …? type statements – such as “Can I really see myself doing a course of home study in psychology and seeing it through to the end?” – because that’s one of the most limiting thoughts we can have, since we often see ourselves askew.

Mindfulness and tradition

Mindfulness has its origins in Buddhism – a belief system that goes back more than 2,000 years. The Buddha’s teachings are gathered in ancient scriptures, the Dhammapada, one verse of which begins with the idea “Mindfulness is the way to Enlightenment”.

Siddhartha Gautama Buddha, usually known simply as the Buddha, spent much of his life spreading his teachings in northern India, sometime between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.

The Buddha never claimed to be a prophet or a deity, though he had found enlightenment through meditation (Buddha means “the one who is awake”) and had gained insight into the meaning of life and the causes of suffering. Just before his death, he appealed to humankind to be mindful (perhaps less relevant to some of us today), to try to escape the endless cycle of reincarnations. He knew that by cultivating mindfulness we could all become enlightened – not by ideas but by attending to direct experience.

Letting go of attachments

The Buddha wasn’t interested in doctrine, and Buddhism isn’t exactly a religion. Instead, he attempted to teach humankind a practical way to deal with suffering. This involved training people in how to let go of “attachment”, the illusory things we all cling to, such as pleasure, desire, comfort, and the past – “illusory” because sooner or later they will all fade into nothingness. Clinging to attachments that will necessarily fade causes all our suffering by letting go, or “freeing the heart”, we can release the mind from illusions that bind us to unhappiness. In the process of becoming more aware and realistic about ourselves and life in general, we attain peace.

To liberate ourselves from desire and find peace as the Buddha taught, we need to know our own minds. Hence, the importance of meditation in Buddhism; it is here that we find stillness and, detached from the claims of the material and the clamour of the emotional, we become mindful. The Buddha taught several different forms of meditation designed to build tranquillity and insight, and foster the attributes of compassion, love, and friendship. Such meditations are at the core of mindfulness practice today.

Buddhist mindfulness

The Buddha set out instructions on how to live in the Noble Eightfold Path and said that following this path was the only possible way to attain self-awakening and escape from suffering.

The path is eightfold because it requires us to develop eight qualities, including Right Effort and Right Concentration (both references to meditation) as well as Right Mindfulness to develop mentally in the ways that contribute to our liberation.

The Buddha also spoke of four distinct forms of mindfulness: of the body, of feelings or sensations, of the mind or mental processes, and of mental objects or qualities. He placed mindfulness practice at the heart of his teachings.

The Four Pillars of Mindfulness

The Four Noble Truths are the most basic formulation of the Buddha’s teaching:

[1] All existence is dukkha – “suffering”

[2] The cause of dukkha is wanting

[3] The cessation of dukkha comes with the cessation of craving

[4] The eightfold path (above) leads to the cessation of suffering.

We can translate these truths into the Four Pillars of Mindfulness: a set of propositions that can save us from error and unhappiness.

. Modern life has its challenges, such as striving for more, or feeling jealousy, which can undermine our wellbeing;

. That loss of wellbeing results from pointlessly wishing things were otherwise – we cling to what we cannot have;

. Through mindfulness we can learn to centre our wellbeing in ourselves, making it much less susceptible to changes in external circumstances;

. We make our own true choices about our life’s path and when challenges do occur, we can face them with awareness.

Mindfulness for health and wellbeing

In the late 20th century, Buddhist-based mindfulness morphed into several new meditation-based approaches to healing. These are grounded in the belief that people can attain some relief from pain or distress by transforming their way of thinking through mindfulness meditation.

The modern history of mindfulness dates from the 1970s and the work of Jon Kabat-Zinn, a molecular scientist and practitioner of meditation. Kabat-Zinn developed a stress reduction programme for people suffering from a wide range of chronic medical and psychological conditions, from heart problems to panic attacks. Held at the University of Massachusetts Medical Centre, USA, his eight-week course was based on mediation and body awareness, combined with simple yoga postures. Relaunched in 1990 as MBSR, or Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, the approach was secular in character despite its roots in Buddhism.

What’s right with you?

Kabat-Zinn examined what makes us all tick and our shared sources of distress. He considered the challenges of modern life, as well as age-old problems such as low self-esteem. His emphasis, though, was as much on “what’s right with you?” as “what’s wrong with you?” He showed that by shifting our focus away from the negative, towards the positive, we can free ourselves from some of the debilitating thoughts and feelings linked with ill-health.

Working on depression

Before long, groups of therapists and researchers began to integrate MBSR with existing psychological therapies, notably Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). This therapy had been designed to help people with acute and severe depression and is based on the idea that thoughts, feelings, sensations, and actions are interconnected. Negative thoughts and feelings can trap people in a vicious cycle, which the therapist helps to eliminate by dividing large problems into small segments, and then showing how to change these negative patterns and feel better as a result. The alliance of CBT and MBSR is called Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), and research shows it to be very effective, particularly in reducing the recurrence of depression.

MBCT works by helping people to understand what depression is – what makes them susceptible to mood spirals, and the reasons they get trapped at the bottom of a spiral. It provides people with a greater awareness of their own bodies, so they can see signs of oncoming depression. Through mindfulness, they can notice their mood turning downwards, and buck the trend, recovering a sense of self-worth.

Many MBCT practitioners also recognise that mindfulness is not just for the ill but can benefit anyone having difficulty coping with the relentless demands of modern life. It has great potential for helping people build resilience at key periods in their lives, such as having a baby, struggling with life-work balance, or coping with ageing.

Flexibility to ACT

While MBSR and MBCT use forms of meditation as their core mindfulness skills, a new therapy – Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) – focuses on three mental skills – defusion, acceptance, and contact with the here and now. Pioneered by US psychologist Steven C Hayes, ACT helps people achieve psychological flexibility – the ability to be in the present moment, with awareness and openness, and act, guided by their values.

Clinical success

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy has been shown to halve the recurrence of depression in patients who have suffered three or more depressive episodes.

A healthcare professional testimony: “It’s great to see someone transformed in eight weeks from a melancholy, withdrawn person to someone who’s receptive and upbeat and take pleasure in the moment.”

The Book of Catastrophe

Jon Kabat-Zinn wrote a doorstopper-sized book about his mindfulness-based stress reduction methods and the experiences that inspired them and came out of them.

The curious title, Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness [1990], is derived from a line in the movie Zorba the Greek, when Zorba speaks of family life as “the full catastrophe”. The acknowledgement of stress and illness in the title set the tone for many later writers on mindfulness. The preface to the book is by Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Zen Buddhist monk with whom Kabat-Zinn had studied Buddhism.

The Mindfulness Revolution

Mindfulness is spreading fast. The ease with which it can be practised, together with its proven, wide-ranging benefits for personal effectiveness and wellbeing, have propelled it into the mainstream in the first two decades of the 21st century.

Any self-help discipline that’s promoted to increase our chances of happiness has a good chance of taking root – especially when it comes with evidence-based research to show it can also make us feel better about ill-health and less likely to fall prey to stress. Add to that the dimension of personal effectiveness – the improvement of concentration, memory, communication, and emotional self-control – and you can see why mindfulness is a flourishing movement.

Jon Kabat-Zinn has said that mindfulness practice is beneficial precisely because we don’t strive towards particular goals: we “befriend ourselves as we are”, hanging out with ourselves in awareness. Yet it is the gains that mindfulness brings that have endeared it to the leading lights of business and public life. Google’s “Search Inside Yourself” programme, started in 2007, introduced mindfulness to more than 1,000 of the company’s employees, and similar initiatives have been taken by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, Fortune 500 titans, Pentagon chiefs, and many others.

Mindfulness at work

The blend of promoting happiness and personal effectiveness has proven especially attractive to employers, who have found that offering mindfulness training within the workplace has benefited their employees and themselves. The employers’ gain is twofold. Mindfulness hones people’s skills, making them more focused, better able to juggle priorities, solve problems, cooperate in teams, lead others, and by being creative. Gains are achieved in innovation and efficiency. But in addition, a happier worker is a more productive worker, and is more likely to stay with the company and show loyalty. Business schools, too, have embraced the practice. Bill George, the former boss of Medtronic, a global medical technology company, and a board member at investment bank Goldman Sachs, introduced mindfulness at Harvard Business School to develop leaders who are “self-aware and self-compassionate”.

The connection between mindfulness practice and training for leadership was strengthened with the publication in 2011 of The Three levels of Leadership, a new model for professional development by UK business coach, James Scouller. This system, which emphasises psychological self-mastery, includes mindfulness meditation as one of its main self-development tools.

Beyond business, mindfulness has taken its message into government and public services. James Scouller has presented his methods to cadets at Sandhurst, the college where British Army officers are trained, and US Armed Forces personnel benefit from mindfulness training in their “Coping Strategies” programme.

In prisons, mindfulness has been employed effectively to reduce hostility and mood disturbance among inmates and to improve self-esteem. And in schools, both teachers and pupils are reaping the benefits of mindfulness: some head teachers believe that the decline in religious assemblies has created a hole in school life – the loss of a daily opportunity for quiet reflection that mindfulness sessions can fill.

Sports performance

Mindfulness has also been adopted in some sporting circles. Research with golfers, runner, and archers reports improvements in performance and a rise in rankings among practitioners. Using mindfulness meditations – such as the body scan – athletes reported feeling “in the zone” which implies being completely absorbed in their actions and experiences. Performance benefits included better concentration, feeling “effortless”, reduced self-consciousness, and a heightened sense of mastery.

Steve Jobs and the business enlightenment

Mindfulness practice in business was not a wild idea that came from nowhere. Eastern mysticism had already nourished several business leaders who cared about the wellbeing of their companies and employees and sought to create an enlightened business culture. Steve Jobs, Apple’s founder, and former chief executive, was a Zen Buddhist, and reported how his beliefs fed into Apple product design. Jobs spoke to his biographer, Walter Isaacson, about the importance of just sitting and observing, and the way that enables you to notice your restless mind. Then calm is achieved, and with that comes a more refined intuition. When the mind slows down, you see, as he put it, “an expanse in the moment”.

A mindful world

In essence, then, mindfulness has spread from its origins in Buddhism to therapeutic settings and the spheres of business, education, and sport, where its application has had measurable benefits.

The mindful zeitgeist

Mindfulness is already effective at an individual and organisational level, but some influential business analysts see a greater potential. They say that mindfulness can change the way society works at a number of different levels.

The power to transform society

Imagine a world in which mindfulness practice was a part of everyday life, and where it was fully integrated into society. What might the benefits be? Reduced spending on healthcare? Higher attainment levels in schools? Improved economic productivity? It is hard to predict, but decision-makers are taking such ideas seriously. In 2014, for example, a parliamentary group was set up in the UK to study how to bring mindfulness into public policy. Also in 2014, mindfulness was identified in a report by J Walter Thompson (JWT) – one of the world’s largest communications companies – as one of ten trends set to shape societal mood, attitudes, and behaviour. Not only was mindfulness significant in itself, but it could exert a profound influence on the other trends shaping our lives.

JWT’S ten trends to shape our world

[1] Wraparound experiences: We’re seeing the rise of immersive entertainment – narratives and brand experiences that work on many levels, using mixed media. An example would be movies shown in elaborate special settings, with interactive audience involvement. Sensory overload of this kind could be read as intellectually demeaning. It implies that many of us are unable to take enjoyment any more in less lavish, more traditional forms of entertainment.

[2] Imperfectionism: Frustrated with commercial spin and the glossy surfaces loved by the retail sector, as well as by affluent customers, many are taking refuge in authentic imperfection. This is seen in a return to home crafts and in re-use of old materials – which, of course, has an ecological dimension too. Since mindfulness values authenticity of the self, many practitioners are likely to carry this through into their surroundings and support imperfectionism. We’re all imperfect, and accepting our flaws is the mindful way.

[3] The new techno-scepticism: Seeing our children addicted to digital devices, and suffering ourselves from information overload, many of us are drawn to a counterrevolution, based on prioritising human values. Face-to-face meetings are being championed in business. Since mindfulness favours direct experience, rather than second-hand experience, many converts to mindfulness will have serious reservations about the digital revolution.

[4] Instant satisfaction: The time lag between ask and receive, and want and enjoy, is getting shorter, with the rise of the on-demand economy, impatience with download speeds, and so on. The Internet accelerates the process of choice, as well as the delivery of what you’ve chosen – waiting is so last year! Mindfulness, however, trains us in patience, and teaches us to find pleasure in modest experiences unconnected with the gratification of our desires.

[5] Mindful living: JWT recognises that mindfulness, once associated with people seeking spiritual fulfilment, is now filtering into the mainstream, with more and more attracted by the idea of blocking out distractions and attending to the moment. Of course, people follow trends for different reasons. Some, thinking mindfulness is “cool”, will gravitate towards an attractive social set. But many will be genuinely looking for ways to bring wellbeing and happiness into their lives; and many too will be trying to find relief from stress and anxiety, and from the pressures of modern living.

[6] Smartphone power: Smartphones are extending their dominion, providing people with access to financial systems, personal health monitoring… and even mindful meditations. There’s nothing wrong with such developments in themselves, but to hitch our pleasures too much to the latest phone technology, and indeed to be emotionally dependent on it, is an example of misplaced priorities – and, in Buddhist terms, the kind of “attachment” that will never bring true contentment, only the illusion of it.

[7] The end of privacy: New technologies make it more difficult for us to avoid being the object of surveillance by private and public organisations. For some, this is a moral battlefield: individuals hate being snooped on, and libertarians object to loss of privacy rights even when it’s arguably in the interests of security. Mindful people will make their own judgement about this: some will mind more than others.

[8] Market mind-reading: With the development of brain-computer interfaces and emotion recognition technology, brands are getting smarter at understanding how consumers think and behave, and marketing to them in a highly personalised way. Many will find it uncomfortable, even infuriating, to have their needs interpreted on the basis of past behaviour: it’s far from mindful.

[9] Image vs word: Visual language, in the form of graphics, emoticons, and the like, seems to be eroding the time-honoured power of the word. This is partly to do with globalisation because it provides a way to reach a worldwide market without the burden of translation. However, for communicating subtle meanings, which mindfulness trains us to appreciate, the image is a much cruder tool than the word.

[10] Cultural mix and match: Cultural mixing within Western societies, and the pick-and-choose culture fostered by the Internet, are encouraging people to create their own blends of beliefs and practices, mixing traditional elements with more recent, or even wholly invented ideas. Since modern mindfulness itself fuses old and new, with elements from different sciences and a great deal of experiment, it’s hard to imagine mindfulness practitioners objecting to such tendencies.

(2) TOWARDS A MINDFUL YOU

By understanding how thoughts and emotions interact, and how they often stem from the past, we can hugely enrich our potential.

What do you think you’re like?

We all have characteristics that make us unique: this is our personality. If we view our personality traits as tendencies, not patterns, we’re less likely to be limited by them. The mindful approach is to get to know ourselves, and use that knowledge to make choices.

Psychologists love to classify, and in the past, studies of personality tended to focus on categorising people into universal “types”. Such assessments have fallen out of favour, though we still come across them in various forms, especially in the business world, when assessing contributions to teamwork.

Shades of grey

Psychologists now speak of traits more than types – a more useful and less reductive approach. For example, we can try and pinpoint our position on a scale between introversion and extraversion – terms that date back to a book by Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, published in 1921. Jung represented these qualities as an absolute pairing: you were either one thing or the other. In fact, no one is wholly extravert (outward) or introvert (inward), and studies by the German psychologist Hans Eysenck and others have shown that most people are in fact a balanced mixture of the two, albeit with a preference in one direction. Another popular scale of assessment, derived from Jung’s contrast of thinking and feeling, runs from something like “tough-minded” to “sympathetic”.

Exploring personality

The emphasis of mindfulness is to realise your potential and bring to light your true options. The true mindful self is found in the unfolding of thoughts, emotions, and actions, so if you think of yourself as a fixed personality type, such as introverted or sympathetic, then you are living in the past, not in the present, and you limit your scope for positive change.

It is, however, possible to use personality traits as a tool for mindful self-discovery. Think about the adjectives associated with personality traits and consider whether you might have appeared – in the past – to have shown these characteristics in your behaviour towards others. Do any of these words chime with how you sometimes describe yourself? Think about these views of your self with mindful attention; this process can help you examine your strengths and weaknesses. Mindfulness will help you to approach such self-assessments honestly and carefully. By avoiding judgement, and considering the questions in the moment, you’re more likely to come up with useful responses that are true to your experience.

The Big Five

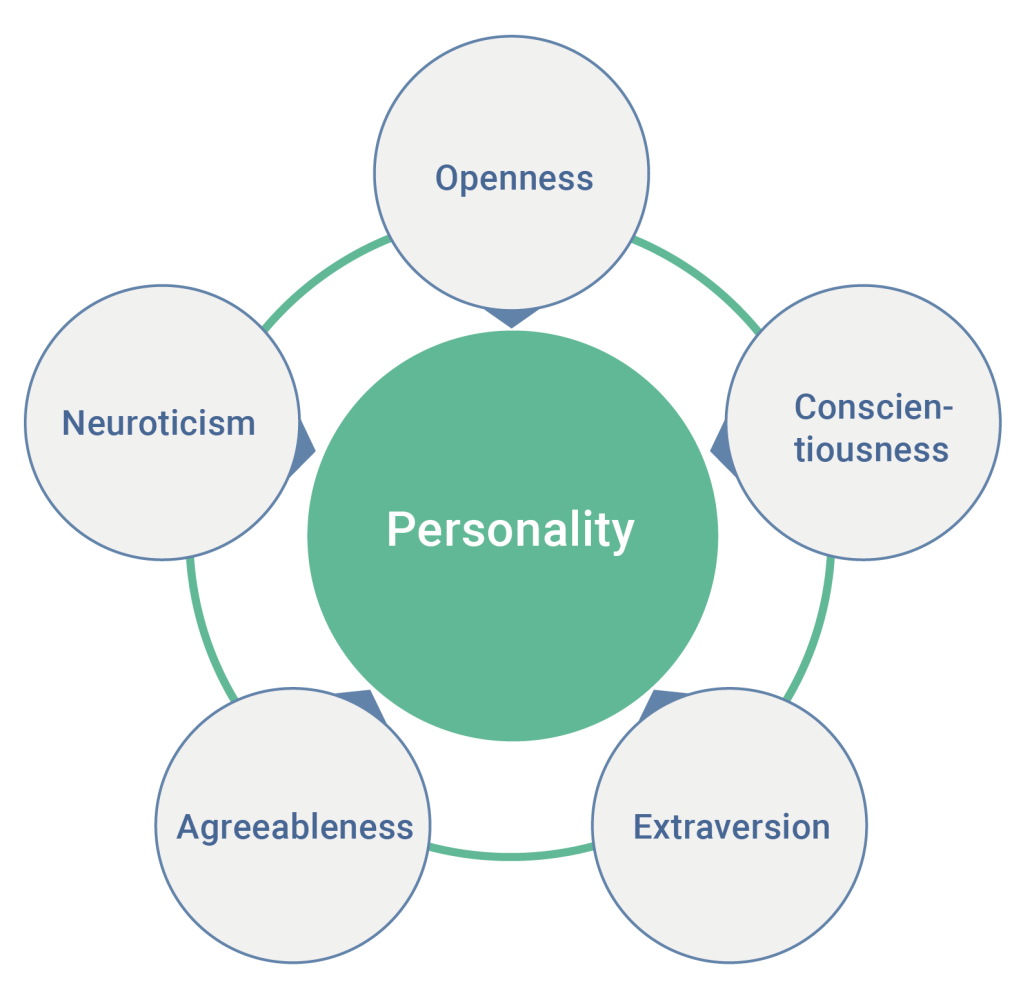

An interesting starting point for self-exploration might be the well-known set of Big Five personality traits. Use the diagram below to think about your position on the five scales: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and sensitivity (also called neuroticism).

Personality types, though never a good excuse, help you understand and forgive your own behaviour. But beware of using them to stereotype yourself.

The Big Five personality traits are a synthesis of psychologists’ attempt to name the entire range of human attitudes and behaviour. Accepting the shortcomings of this listing, you can still use it as a cue for self-discovery. Scan the word scales given for each category; if neither extreme in the scales is a word you’d use to describe yourself, see if you can think of a word, falling somewhere on the scale, that would. Experiment to spin off further self-descriptive words with similar meanings.

Openness:

Curious ≤ Convinced

Experimental ≤ Selective

Creative ≤ Consolidating

Imaginative ≤ Logical

Independent ≤ Consistent

Conscientiousness:

Responsible ≤ Relaxed

Dutiful ≤ Self-motivated

Careful ≤ Spontaneous

Meticulous ≤ Decisive

Perfectionist ≤ Self-tolerant

Extraversion:

Assertive ≤ Flexible

Energetic ≤ Calm

Sociable ≤ Self-contained

Talkative ≤ Contemplative

Expressive ≤ Reticent

Agreeableness:

Compassionate ≤ Implacable

Cooperative ≤ Sceptical

Compromising ≤ Determined

Amenable ≤ Resolute

Responsive ≤ Composed

Sensitivity (also called neuroticism):

Optimistic ≤ Questioning

Resilient ≤ Empathetic

Confident ≤ Tentative

Inspiring ≤ Impressionable

Trusting ≤ Watchful

Disposed towards the moment

Are you naturally mindful?

Do you enjoy listening to what people have to say? Do you make quality time for those closest to you? If so, you may be “dispositionally mindful” with an existing measure of mindfulness in your psychological make-up; you are also likely to take mindfulness meditation like a duck to water. If you prefer simple pleasures to striving, for instance, you may be dispositionally mindful.

Mindfulness is a technique but it’s also a personality trait (though not recognised as one of the Big Five, as described above). If self-awareness comes to you readily and you already tend to inspect your thoughts, sensations, and emotions on a regular basis, you’re predisposed to be mindful. Scientific studies have shown that people who are dispositionally mindful respond better to stress and are less susceptible to negative mood states than others; they have better cardiovascular health; and some (though not all) of their cognitive functions are enhanced. Other research has indicated that dispositional mindfulness may be encouraged by aerobic exercise, although more work needs to be done before this can be stated with certainty. Whether you are innately mindful or not, practising mindfulness through meditation builds on your pre-existing human capabilities. If you think of mindfulness as an inner spotlight that you can direct towards yourself at any moment for the purpose of self-discovery, then meditation helps to make that spotlight brighter and more focused.

At this point, it’s important to distinguish between self-awareness and self-absorption. Many people think and talk frequently about their inner life, and in particular their emotions. Emotional intelligence is valued highly today, and those who aspire to it often understand that it needs to be grounded in empathy – that is, the ability to put yourself in another person’s situation, and to identify with what they’re feeling. This in turn requires that you have a good appreciation of your own feelings. Unfortunately, many introspective people, who would claim to be emotionally intelligent, may sometimes come up with inaccurate observations about their own feelings: they shine the spotlight on the right place but not with true illumination.

Body language

It’s been said that the one thing we don’t know about ourselves is the thing that other people know only too well. It’s possible to think of yourself as confident, for example, while in fact being rather anxious in company. You can’t necessarily detect what messages your own body language is conveying, whereas the people in the room with you will detect your anxiety from the high pitch of your voice, or the way your eyes dart about, or how you fiddle with your bag or other possessions. Those predisposed to be mindful are unlikely to miss such symptoms. They’ll be aware of themselves and be able to identify the kinds of situation that tend to make them uncomfortable. They might even be able to detach themselves from their discomfort, at least sometimes.

Mindful markers

Analysing your behaviour, your emotional responses, and your attitudes to people helps gauge your level of dispositional mindfulness.

To help you assess your level of pre-dispositional mindfulness, ask yourself which of the following statements apply to you. The more you tick off and agree with, the more likely it is you have a mindful temperament, although there’s nothing systematic about the list.

✓ You’re seldom surprised when people make comments about your strengths or your weaknesses.

✓ When feeling anxious, your first step is to try to separate yourself from your anxiety and look at it from the outside.

✓ When feeling angry, the first thing you do is spend several seconds trying to clear your head before saying or doing anything.

✓ You could list, if asked, a number of regular habitual reaction patterns that you’re prone to experience in certain situations.

✓ When thinking about past or future events, you sometimes stop yourself and consciously return to the present.

✓ You often respond with gratitude, pleasure, or wonder to positive events you observe around you.

✓ You don’t fight it when good things in your life come to an end, since you know it’s beyond your control.

Wheel and compass

Doing and being minds

The mind is a wonderfully versatile instrument for steering us through the day. It can also be a compass, providing readings to help us navigate by. But often it forgets to take its bearings, making a voyage a turbulent one.

As the day starts, you think ahead to what the day holds for you. You picture events and wonder how they’ll go. You’ll be hopeful about some things, anxious about others; some will be neutral – you’ll simply be reminding yourself that you must make time for an errand or to follow up a task that needs doing.

You might be of a relaxed mind, but your mind will be in “doing” mode in which one thought leads to the next. What’s more, you are being carried along with it. Some of your thoughts are reflective, some are decisions to act, but there’s still no mindfulness here. Your autopilot might be happily chugging along, and even giving some enjoyment, but it’s autopilot, nevertheless. A relaxed mind isn’t a mindful one.

Choiceless awareness

The alternative mind mode to “doing” is “being”. You might find yourself worrying about certain things over breakfast, but you don’t chastise yourself for these worries or switch your attention to the future (“Is it four days or three?”). Instead, you shift into “being” mode. You direct your attention to the present moment, observing your thoughts and worries without getting drawn into their content. You bring a gentle awareness to yourself and your true feelings. This is how you can let go of the “doing” mode and move into the “being” mode – the compass – where you can become aware of your true direction.

Signs of the “Doing” Mode

We’re operating in “doing” mode whenever we’re not simply being. The following checklist – with annotated examples – will help you recognise some categories of the “doing” mode.

Self-criticism and constant analysis of your decisions are signs of a mind locked in “doing”.

[1] Example: Wondering if you’ve said or done the right thing.

Judgement – Measuring what happens, or has happened, against what “should” have happened.

[2] Example: Thinking that you should be more tolerant, proactive, or productive.

Self-Criticism – Taking a critical stance in your inner dialogue with yourself – berating yourself for your errors.

[3] Example: Deciding whether to move house, or go to the shop, or how to cheer up a friend.

Problem-Solving and Deciding – Working out what action to take and tracing the possible consequences of that action.

[4] Example: Feeling angry with your neighbour and wondering how he could have been so thoughtless.

Engaging with Feelings – Inhabiting emotions and reliving the narrative behind them.

[5] Example: Recalling the last time you enjoyed yourself so much or reminiscing about a romantic evening.

Remembering – Taking your mind back to the past, whether anxiously, regretfully, pleasurably, or with any other emotion.

[6] Example: Wondering if there’ll be refreshments at a party or wondering if your home insurance would cover you if you broke your glasses.

Speculating – Taking your mind into the future, whether anxiously, hopefully, or with pleasurable anticipation.

[7] Example: Protesting on hearing someone telling a lie or giving someone a hug when they start crying.

Reacting – Showing involuntary actions to experiences rather than pausing to consider your response.

Alive in the present

Taking a step back in our minds from doing and instead moving into a state of pure, present being is a key skill of mindfulness. Attending to our sensations, thoughts, and feelings means that the negative energies in our minds lose much of their influence.

Moving Into Being

The mind’s “doing” mode is the mode of efficiency – the realm in which we get things done in the physical world. We have seen that this mode has its negative aspects – it is here that we react automatically, worry about the future, and regret the past – but it offers up so many possibilities for moving towards our personal goals. In comparison, the “being” mode may seem dull and unappealing: after all, what’s the point of just sitting there, with a still mind, unless you’re a mystic or a Buddhist in a deep state of absorbed concentration?

Dropping into being

The “being” mode is not just for the spiritually minded: the basic, non-judging (or choiceless) awareness that comes to the foreground when you drop into “being” mode has been a vital inner resource from the start of our conscious lives, and it’s available to us at every moment. It can give us nourishment and calm within our busy lives of seemingly endless doing. What we gain from this is not spiritual wisdom but a practical way to inhabit our everyday lives more fully.

The challenge of being

When you combine the “being” mode with noticing your sensations, thoughts, or feelings, you enter a mindful state, with its attendant physical and psychological benefits. Achieving that state takes practice; if you just try “being” for a few seconds, you won’t find it easy. You’re in the middle of following a train of thought, which your mind won’t want to abandon.

So, what does “being” look like? This thought experiment will give you an idea. Imagine that you’re sitting in the park, looking intently at a rose. You let go of everything in your mind except the sensation of the rose; there’s no room in your thoughts for past or future, for anxiety, or for any other emotion. If a thought intrudes, you simply let it drift out of your mind in the same way that it drifted in. You don’t battle with that thought because that would take you back into the doing mode. You have chosen mindfulness.

In a mindful state, thoughts and emotions are neither welcome nor unwelcome.

Q: What should I do if an emotion or distracting thought suddenly pops into my head?

A: Simply observe it, without engaging with it, without judging it, without doing anything with it at all.

Signs of the “Being” mode

Get to know the characteristics of the “being” mode through this checklist; compare its features with those of the “doing” mode (above). Notice that it is in the nature of the being mode that many of its features are expressed in the negative. Use this list when you look back on your first attempts at just being, to see whether your thinking attained any of these qualities, or non-qualities.

[1] Living in The Moment – “Being here now” and not engaging with any thought of past or future that happens to come into your mind.

[2] Non-Judgement – Not measuring what happens or has happened against what should be happening or should have happened. “Should” thinking has no place here.

[3] Acceptance – Not engaging in a critical or disappointed dialogue with yourself and being compassionate with yourself whenever you unintentionally think of any kind of error you’ve made.

[4] Attention – Focusing the mind on its own experience in the moment and, if it gets distracted, gently returning your focus to the object of your attention.

[5] Passivity – Not making decisions, planning or problem-solving: these all belong to the “doing” mode.

[6] Responsiveness – Not reacting to any unwanted inner or outer distractions [thoughts or sensations], but simply noticing them and letting them drift away.

[7] Non-Engagement – Not getting absorbed into an emotion or unwanted thought that happens to cross your mind, remaining distant from an emotion’s underlying story.

Time warps: stuck in the past, anxious about the future?

Our true home is the present. This is the only place where our lives are actually occurring. Learning to live mindfully in the here and now will make us more grounded, more balanced, and happier.

We learn from the past – our treasury of memories and source of emotional support – while thinking about the future may spur optimism, determination, and ambition. Even so, it isn’t good for us to spend too long in these places: mindfulness can reground our attention in the present.

The power of the past

Our past is made up of things we have experienced, and some of these experiences may have been bad ones. Someone might have harmed us, making us wary in the present, or we might have done something we deeply regret. Many present anxieties have roots in our past, even if we’re unable to trace them.

We can’t change the past, so we may try to make up for mistakes by denying ourselves pleasures or trying to do now what we failed to do before. However sincere these attempts, we may find life is overshadowed by guilt or regret, dragging our thoughts back to the past and limiting our chances of happiness in the present. If guilt is a complaint against ourselves, the past is often a cause of complaints against others. Anger is easily revived by memories of past wrongs, surging in fresh aggression; while resentment “simmers”, with low-level hostility.

Through mindfulness you can harness the positive power of the present to change your relationship with the past. No pitched battle is necessary. The present has merely to be attended to, and the power of past events will fade away.

Jailbreak

Imprisoned in guilt or shame, we need mindfulness to plan our great escape. The key is to learn how to stop judging ourselves, (see: Silent witness above). It’s only our distorted perception, and more specifically our lack of self-compassion, that makes a prison of the past. The cell we’re locked in is of our own making and mindfulness meditation gives us the key to unlock these distortions. When we give attention to the present moment the past releases us from captivity. With the key in our hands, mindfully we unlock the door and walk free.

The past, if we can’t come to terms with it, can breed guilty or resentful feelings, while the future is an imagined prospect that may fill us with anxiety.

| THE PRISON BARS OF GUILT | THE PRISON BARS OF SHAME |

| Being a poor son, daughter, or parent | Failing to excel |

| Being a poor partner | Failing to control your emotions |

| Being unable to cope | Failing to be responsible |

| Being unable to succeed | Failing to be normal |

| Being selfish | Failing to fit in |

Lifting the lid

We are all capable of thinking positively. What sometimes holds us back are our old habits of thought and feeling, some with roots in the distant past. Understanding what magnifies these bad habits and what’s capable of weakening them is an important step in our mindfulness journey.

Letting go of negative thoughts and feelings

Most of us know individuals who seem spontaneous, immersed in the world, and who spread energy wherever they go. In their presence, we may even feel a kind of awakening, a call to action, and feel that our own responses to the world are more sluggish than theirs.

These people appear so much more engaged because they have successfully turned down their autopilot. We’ve seen how autopilot can dull us to the potential for experience offered, and blunt our potential for inner growth, giving us a vague sense of dissatisfaction or staleness.

Auto thoughts

If you’re having negative thoughts about yourself, such as “This is beyond my capabilities”, “Why should I think it’s going to be better this time?” or “Nobody will thank me for doing this,” negative emotions will almost inevitably follow in their wake. This thought-plus emotion pairing will soon get ingrained in your mind as a pattern – a reflex that impacts on your mood whenever certain kinds of situation recur.

What results is a feedback loop: you believe the voice inside you that says you’re useless, because that’s how you feel; and you feel that way on account of your inner voice. Such deep patterns of thinking and feeling whittle away at your wellbeing, subtly and not always noticeably, until one day you realise how low, irritable, or fatigued you are. All of this happens so automatically you don’t even realise you have a choice in the matter.

It needn’t be this way. We all have rights of refusal when it comes to negative thoughts: we don’t have to believe them, even if it’s impossible, at least initially, to keep them, and the emotions that tag long with them, out of our heads. What we need, to turn off the inner mechanism of negativity, is mindfulness meditation. We may not be able to get rid of negative thoughts, but we can learn to treat them with accepting curiosity and shift our relationship with them, taking them less seriously.

Not controlling

If you want to rid yourself of negative patterns of thought and emotion, wilful control rarely works. Deciding you’re going to resist the thoughts and feelings involved in the complex chemistry of low esteem, hopelessness, and disappointment will only bring further tension. You cannot defeat such problems by putting a lid on them, and containment only makes the pressure build up further – an idea expressed succinctly by Carl Gustav Jung: “What we resist, persists”.

If you can’t contain an explosion, the obvious approach is to stand back from it. Mindfulness does this, though without any sense of running away.

Keeping a mindfulness journal

Practising mindfulness is a highly subjective experience. The thoughts you have, the things you learn about yourself, and the unconscious mental habits that you uncover are all intensely personal and often fleeting. For some people, recording their experience in a journal is a very useful exercise because it helps to objectify their thoughts, sensations, and emotions, so that they can be used to refine their meditation in future. A journal can record when you practised, for how long, and what type of meditation you carried out, so providing important markers of your progress. Use these prompts when writing in your journal:

. What type of meditation?

. When and how long?

. Physical sensations felt – how did I respond?

. Thoughts and emotions – what arose and how did I deal with it?

. Did I get distracted – by what?

. Useful tips to keep me in the moment.

. Any changes in my everyday life?

. What have others said about me?

– Be Honest: Try to write in your journal every day. Record whatever information or observations you find useful. There’s no right or wrong about what to write in the journal, other than the need to be completely honest.

Why habits take time to break

Deep-rooted habits can be a block to happiness. While practising mindfulness meditation is the most effective way to dissolve the force of habit, we can make a start by bringing compassionate attention to our habits and increasing our self-understanding.

It can feel at times as if our lives are living us, rather than we are living our lives. Autopilot, as we’ve seen, takes our choices away from us without our consent.

Bad habits are reactions to situations, laid down in your body and mind like the rings in a tree truck. To be reactive is to think, act, or feel instantaneously without allowing yourself a moment to let the situation sink in. As a result, a reflex that’s developed over time, and has become as ingrained as a tree’s rings, repeat itself without your having a say in the matter. Each occasion on which this happens reinforces the pattern; habits get stronger over time.

Mindfulness gives us the tools to recognise habitual thoughts and reactions, and let them pass through consciousness without effect. With mindfulness meditation we can start to get our choices back, but we need to be persistent with our practice once we’ve begun, since habit will always try to reassert itself.

When habit takes the lead

Here are some examples of habitual, autopilot reaction – they are likely to seem familiar.

. You meet someone who disliked you at school, and find that you’re unable to respond to their friendly overtures

. You believe you’re no good at public speaking, and you panic when asked to make a leaving speech for a colleague

. You feel yourself getting tongue-tied when talking to your daughter’s teacher, because you know she’s very bright and you feel inferior.

Pause, then play

Mindfulness helps us to widen the gap between stimulus and response, giving us more control.

Our brain chemistry is changed by our repetitive behaviours, but we don’t need to be enslaved by our habits. With mindfulness, we can break free.

Q: Can’t I defeat habit simply by saying “no”? Why do I need a programme of mindfulness meditation?

A: Mindfulness lets you pause and notice your impulses.

Chart your good and bad habits

To improve your awareness of how autopilot and involuntary habits affect your life, try charting your habits – both good and bad. Make a note of which negative habits are most entrenched, and which habits you consider positive – those you might wish to keep. Use the prompts below for your thoughts and write your thoughts and feelings in your mindfulness journal. You can return to this record as you progress through your mindfulness meditation practice to gauge your progress.

Good habits – What emotions do I often have that make me happy? This emotions checklist should be used to help you name your feelings as precisely as possible:

Contentment – Gratitude – Love – Patience – Admiration – Pride – Excitement – Inspiration – Pleasure – Happiness – Calm

Feelings may change between (when) writing about yourself, about your family, about your friends, about your relationships, and about work. It is imperative to differentiate when writing your journal entries about your feelings in each of these categories.

Bad habits – What emotions do I often have that make me unhappy? This emotions checklist should be used to help you name your feelings as precisely as possible:

Confusion – Frustration – Irritation – Disappointment – Anger – Envy – Jealousy – Oppression – Impatience – Grievance – Helplessness – Hopelessness – Claustrophobia – Bewilderment – Boredom

Likewise, feelings may change between (when) writing about yourself, about your family, about your friends, about your relationships, and about work.

Loosening habit’s grip

You can only dislodge deep-seated habits of thinking and feeling over time – but it will be greatly helped through mindfulness meditation. You can prepare for this by making changes to some of your unproductive outer habits – the things you do routinely, unquestioningly.

Towards a more authentic you

We’re exposed every day to a countless flow of phenomena – things we hear, read, observe, or perceive in other ways. Much of this information could be useful, suggesting new options for us to take up, or new paths to follow – if only we were willing to attend to it. By a process known as “selective perception”, we filter out stimuli that don’t fit into our image of our own lives. From time to time, it pays to pull back and take in a wider-angle view of the world. We might then see more fulfilling options that are available and that could help us lead fuller lives. To realise our potential is, in part, to say goodbye to false identities and live more authentically, finding our true selves.

Keeping busy

One of the habits many of us have is keeping endlessly busy, throwing ourselves into action to avoid making time for contemplation. Unconsciously, we fear that introspection might force us to face uncomfortable truths about ourselves. Work provides a compelling distraction. Many stay late at the office, telling themselves that they need to put in the hours to compete with colleagues, or to impress the boss, but in truth so much of a person’s identity is tied up with work that many would feel lost without it.

Being overburdened by tasks may also be unconsciously attractive because it gives us an excuse to be selective. For example, we might have issues with a family member that we know we should address in a long heart-to-heart chat, but we fear the buried emotions such a conversation might dredge up from the past. So, we tell ourselves that we just can’t make time for it.

Ignoring things you dislike can be a limiting habit. Keep a little ambivalence in your life – your mind will be more open and your experiences more interesting.

Getting to know you

Another common habitual thought pattern is a tendency to make quick judgements about people we meet, then stick to them, even though they were based on extremely flimsy evidence. In fact, giving people the chance to be who they really are, in that moment, is an attitude that follows on naturally from mindfulness.

As a counterweight to this tendency, try seeing people with fresh eyes. Ask them questions you wouldn’t normally ask; solicit their opinions; and listen attentively to what they have to say. Your perceptions will almost certainly expand beyond the blinkered view you started with. Given the limitations of our understanding, it’s hardly surprising when people turn out to be nicer than we thought.

Getting to know your mind storms

At times of stress, our thinking speeds up as we rush in panic from one bad thought and feeling to another, trying to find a solution. You can use these mind-storm experiences as a way into thoughtful self-analysis. Ask yourself these questions and write the answers in your mindfulness journal:

. What kinds of situation tend to trigger your mind storms?

. Are there any thoughts that keep recurring in your mind storms? Are any of these thoughts obviously true or false?

. Are there any memories that keep coming into your mind storms? If so, why do you think they surface like this?

. Are there any recurrent emotions in your mind storm? What’s the effect of such emotions on your thinking and behaviour?

Five habit-looseners

Here are five simple ways to move towards a more authentic self. Authenticity is not just about you: it’s also about the quality of your relationships. Getting used to making lifestyle changes like this prepares the way for doing deeper work on autopilot reactions through mindfulness meditation.

[1] Appreciate kindness when people show it. Tell them that their kindness matters to you.

[2] Listen to people’s stories with your full attention – not just politely, but because it really matters.

[3] Ask a colleague their opinion about something – not a work question, but something beyond your normal range of conversational topics.

[4] Talk to anyone who approaches you in the street – whether they’re begging, trying to sell something, or doing a survey.

[5] Don’t take mobile phone calls when you’re with someone: concentrate fully on being with them.

Wandering mind

Settling down to a task, we’re unlikely to find that we can give it 100 per cent of our attention – most of us would settle for 70 per cent. One thing is clear: our lives could become much more productive and fulfilling if we could only master the art of concentration.

How to concentrate better

Think of yourself composing an email to a friend or following a new recipe from a book in the kitchen. Do you give your wholehearted attention to the matter, or does your mind wander from time to time? Most probably, you’ll confess to wandering. You might find yourself straying along a by-way – a branch of thought that starts with the matter in hand but soon goes off at a tangent. Alternatively, thoughts might surface that are completely unconnected to what you’re doing – perhaps reprising something you were thinking about earlier.

Worries, in particular, often resurface like this. Before starting a new task, we usually push any preoccupations to the back of our minds. But they have a nasty habit of coming back and clamouring to be noticed. Whether we give them the attention they crave depends on how mindful we can be.

Going off course

We spend a significant part of our lives engaged in “mind wandering” – daydreaming or straying from the present moment. This can be part of the helpful process of reflecting on a problem, taking a break from it, and then returning to it later. It is important to understand that it is in the nature of the mind to wander, and this can facilitate learning.