INTRODUCTION

THIS PAGE is a consolidation of the greatest questions man has ever asked. Ranging from ancient philosophers to contemporary politicians, the focus is to distil the intricate ideas of humanity’s most influential thinkers into a better understood and easily digestible narrative. It will span both Eastern and Western traditions.

The word “philosophy” like so much else in Western philosophy, is Greek in origin: the original word philosophia means “love of wisdom”, but while that might be a nice description of the subject, it doesn’t tell us much about what it actually is.

Perhaps it is best to think of philosophy as being “what philosophers do” – an activity, rather than a study – which is to use the human capacity for rational thought to pose and attempt to answer fundamental questions about the universe and our place in it. This may be a broad definition of a very broad subject, but it is a useful way to distinguish philosophy from other ways in which we try to make sense of the world we live in. At its heart, philosophy is thinking: thinking about why things are the way they are, how best we should live our lives, how we can be certain about what we know, and what meaning, if any, there is to our existence. The same questions are asked by religion and science, but while religion gives answers based on faith or belief, philosophy uses reasoning, and where science provides description, philosophy seeks explanation.

Philosophy as an academic subject studies the ideas of the great thinkers, and it is these that will dominate this page, but it is also something that almost everybody indulges in: we all spend some of our time wondering about the same questions addressed by the great philosophers through discussion or debate. Often, we will disagree, and just as often, we will find no definite answers – philosophers, too, have widely differing opinions, and frequently come up with more questions than answers. But throughout history philosophers have provided us with different ways of looking at these questions, and by understanding their thought processes we can learn how to organise our thoughts and arguments.

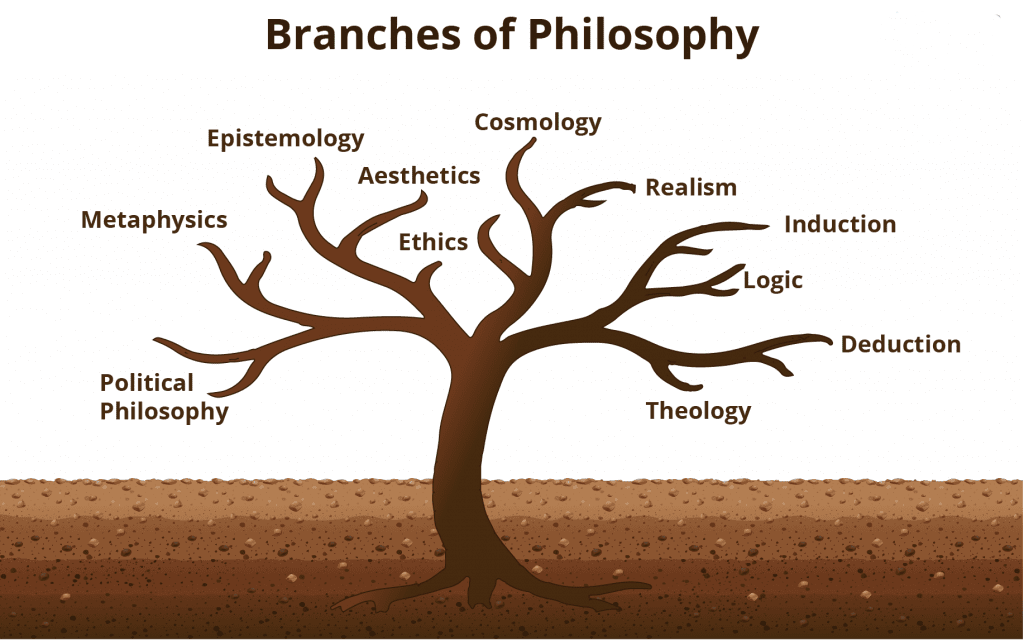

Branches of philosophy

The first philosophers that we know of appeared in the sixth century BCE in ancient Greece. As civilisations became well established and more sophisticated, thinkers began to question traditional explanations for the workings of the universe and society, and sought answers based on rational thought rather than convention or religion. The first question they addressed was “What is the world made of?” – the branch of physics we now call metaphysics. From this, they also began to question how we can be sure of what we know (the branch of epistemology) and the nature of our existence (ontology). Slowly, they developed a systematic way of analysing their arguments, logic, and techniques of questioning to elicit fundamental ideas. This opened up the field of moral philosophy, or ethics, which is concerned with concepts such as justice, virtue and happiness, and this in turn led to many philosophers’ exploring what kind of society we want to live in (giving rise to the branch known as political philosophy).

. Metaphysics

For the first philosophers, the burning question was: “What is everything made of?” At its most basic, this is the central question of a branch of philosophy known as metaphysics. Many of the theories proposed by the ancient Greek Philosophers – the notions of elements, atoms, and so on – formed the basis of modern science, which has since provided evidence-based explanations for these fundamental questions.

Metaphysics, however, has evolved into a field of enquiry beyond the realms of science: as well as dealing with the make-up of the cosmos, it examines the nature of what exists, including such ideas as the properties of material things, the difference between mind and matter, cause and effect, and the nature of existence, being and reality (a branch of metaphysics known as ontology). Although some philosophers have challenged the validity of metaphysics in the face of scientific discovery, recent developments in areas such as quantum mechanics have renewed interest in metaphysical theories.

. Epistemology

It soon became apparent to philosophers in ancient Greece that there was an underlying problem with all the questions they were attempting to answer, best summed up by the simple question: “How can we know that?” This, and similar questions about what sort of thing we can know (if anything), how we can acquire knowledge and the nature of knowledge itself, have preoccupied Western philosophy ever since, forming the branch of philosophy known as epistemology.

Some philosophers believe that we acquire knowledge by experience and through the evidence provided to us by our senses – a view known as empiricism; others think that knowledge is primarily acquired by a process of reasoning, a view known as rationalism. The division between empiricism and rationalism helped to define various schools of philosophy until the 19th century. Other areas of epistemology, meanwhile, deal with the connection between knowledge and concepts such as truth and belief.

. Ontology

Considered to be the major branch of metaphysics, ontology is the field of philosophy that examines the nature of existence and reality. It is distinct from epistemology in that it is not concerned with our knowledge of a thing, but addresses the questions of whether something actually exists, and what sort of things can be said to exist.

As well as trying to establish what can be said to exist, ontology also attempts to identify the properties of things that exist, and categorise them according to these properties and the relationships between them. Naturally, this entails an examination of the meaning of the terms “existence”, “being”, and “reality” – a central concern of ontology – and concepts such as the substance or essence of an object, its identity, and the difference between concrete and abstract objects: can concepts such as “love” and “memory” be said to exist in the same way as a table or a rock?

. Logic

In seeking answers to questions about the universe and our place in it, philosophy is distinguished from religion or mere convention by its use of reasoning. A philosopher proposes ideas as a result of a thought, and has to justify his or her assertions with rational argument. Various techniques have been devised to show whether an argument is valid or fallacious, forming the branch of philosophy known as logic.

In simple terms, logic is the process of inferring a conclusion from statements known as premises, either deriving a general principle from specific examples (inductive reasoning) or reaching a conclusion from general statements (deductive reasoning). The classical form of logical argument, the syllogism, consisting of two premises and a conclusion, was formalised by Aristotle and remained the mainstay of philosophical logic until advances in mathematical logic brought in new ideas in the 19th century, and symbolic logic opened up new fields of philosophy in the 20th century.

. Moral philosophy and ethics

While the earliest philosophers sought to understand the wider universe, it was not long before philosophy turned its attention to humans themselves, and the way we lead our lives. The idea of virtue was central to life in classical society, but difficult to define; concepts of good and evil, happiness, courage, and morality became the subjects of debate in the branch of philosophy known as ethics, or moral philosophy.

In trying to ascertain the nature of a virtuous life, philosophers raised the question of what the goal of life should be – what is its “purpose”? How should we lead our lives, and to what end? The concept of the “good life”, eudaimonia, figured largely in Greek philosophy, and embodies not only a virtuous life, but also a happy one. Several different schools of thought emerged as to how this “good life” could be achieved, including the cynics, who believed in harmony with nature, the Epicureans, who believed pleasure to be the greatest good, and the stoics, who believed in acceptance of things beyond our control.

. Political philosophy

Where ethics and moral philosophy seek to define virtue and what constitutes the “good life”, the closely related branch of political philosophy examines the nature of concepts such as justice, and what sort of society can best allow its citizens to lead “good” lives. The problems of how society should be organised and governed were of paramount importance not only to classical Greece, but also in the development of nation states in China at much the same time, and elsewhere as new civilisations emerged.

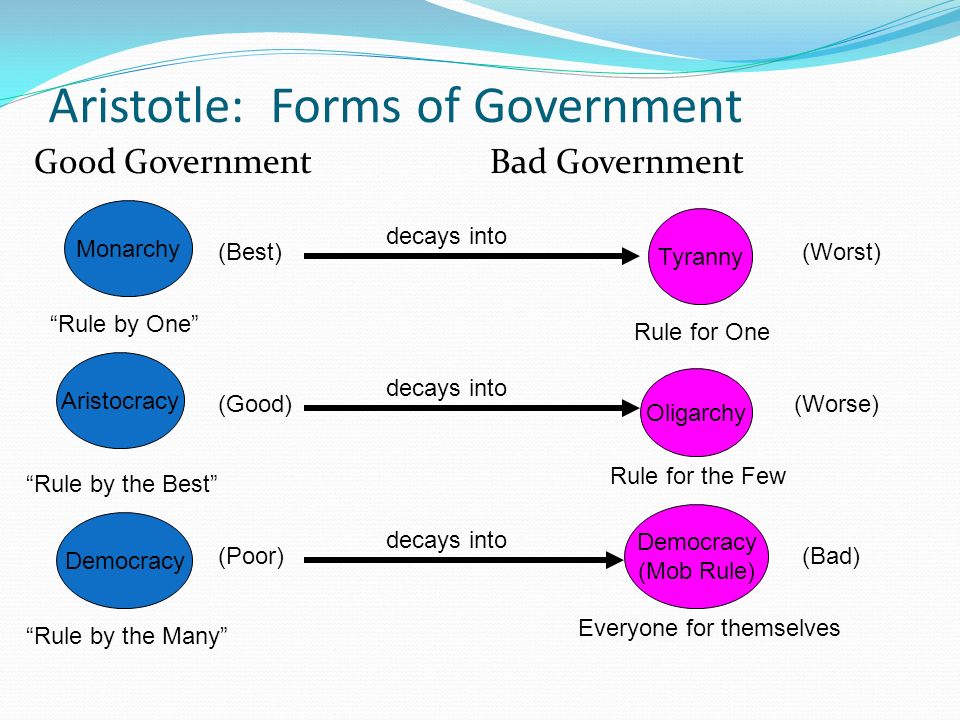

As a branch of philosophy, political philosophy deals with ideas of justice, liberty and rights, and the relationship between a state and its citizens. It also examines various forms of government, such as monarchy, aristocracy, oligarchy, tyranny, and democracy; how each affects the rights and freedoms of the individual, and how they exert their authority through rule of law.

. Aesthetics

As the classical Greek philosophers sought to define concepts such as virtue and justice, giving rise to the branches of moral and political philosophy, they also asked the question: “What is beauty?” This is the fundamental question of aesthetics. As a branch of philosophy, aesthetics tries to establish what, if any, objective criteria there are for judging whether something is beautiful, but in a wider sense also examines all aspects of art – including the very basic question “What is art?”

At various times in history, the emphasis of aesthetics has moved from what constitutes art to the religious or socio-political significance of works of art, a general theory of our application of art and how we perceive it, and the process of artistic creativity itself. Philosophical and ethical problems are also raised when considering such matters as the authenticity of a work of art or the sincerity of its creator.

. Eastern and Western philosophies

Although the tradition that began in ancient Greece still tends to dominate philosophical discussion in the Western world, philosophy is by no means restricted to that single tradition. Thinkers such as Laozi and Confucius in China also founded their own traditions of philosophy from different starting points, as, arguably, did Buddha in India. For them, and subsequent Eastern philosophers, questions of metaphysics were considered to be adequately explained by religion – hence the Eastern traditions are much more focused on concepts of virtue and the way in which we should lead our lives. In China especially, this moral philosophy was adopted by the ruling dynasties and took on a political dimension. Eastern and Western philosophies developed very separately until the 19th century, when European philosophers, notably Schopenhauer, began to take an interest in Indian religious and philosophical thought. Elements of Eastern philosophy have subsequently been incorporated into some branches of Western philosophy.

In India and China, the differences between philosophy and religion are less clear than in the West.

. Philosophy vs religion

Religion and philosophy offer two distinctly different approaches to answering our questions about the world about us – religion through belief, faith and divine revelation, and philosophy through reason and argument – but they often cover much the same ground and are sometimes interrelated. Eastern philosophy developed side by side with religion, and Islam saw no incompatibility between its theology and the philosophy it inherited from the classical world, but the relationship between Western philosophy and Christianity was very often uneasy. Church authorities in the medieval period saw philosophy as a challenge to their dogma, and Christian philosophers risked being branded as heretics for attempting to incorporate Greek philosophical ideas into Christian doctrine. But more than that, philosophy also brought into question issues of belief as opposed to knowledge, faith as opposed to reason – questioning, for example, whether there was any evidence for miracles or even whether the existence of God could be proved.

. Philosophy and science

Throughout much of the history of philosophy, there was no such thing as science in its modern form: in fact, it was from philosophical enquiry that modern science has evolved. The questions that metaphysics set out to answer about the structure and substance of the universe prompted theories that later became the foundations of “natural philosophy”, the precursor of what we now call physics. The process of rational argument, meanwhile, underpins the “scientific method”.

Since the 18th century, many of the original questions of metaphysics have been answered by observation, experiment and measurement, and philosophy appeared to be redundant in these areas. Philosophers have since changed their focus to examine science itself. Some, like Hume, challenged the validity of inductive reasoning in science, while others sought to clarify the meaning of terms used by science, opening up a “philosophy of science” that considers areas such as scientific ethics and the way science makes progress.

Greek philosophy

The beginnings of Western philosophy are closely linked to the rapid growth of Greek culture and society from around the sixth century BCE. In addition to mainland Greece and the Greek islands, Greeks had settled throughout the eastern Mediterranean, and southern Italy and Sicily. It was in one of these colonies, Miletus on the coast of modern Turkey, that the first known philosophers appeared. Led by Thales, the Milesian school of philosophy inspired subsequent generations, and the practice of philosophical thought and discussion rapidly spread across the Greek world. Athens proved to be the ideal place for philosophy to flourish, and produced perhaps the three most influential philosophers of all time – Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. They were followed by four main schools of thought: the cynics, sceptics, Epicureans, and stoics.

Greek influence reached its height under Alexander the Great, but after his death in 323 BCE, Greece fragmented into conflicting factions and its cultural influence also waned, to be overtaken by the increasingly powerful Roman Empire.

. Thales of Miletus

Sometime around the beginning of the sixth century BCE in the Greek colony of Miletus, a man called Thales, dissatisfied with traditional explanations for the workings of the universe, sought to find his own answers by rational thought. As far as we know, he was the first to do this, and is considered to be the first philosopher. The problem that most concerned him, and became the abiding interest for all of the “pre-Socratic” philosophers, was: “What is the world made of?”

Thales’s answer was a surprising one: he believed everything was made from a single element: water. His reasoning was that water is essential to all life and appears in several forms – as well as a liquid, it is solid when cold, and a gas when hot. What’s more, the solid earth seemed to be floating on water, so it probably emerged from water and was therefore made of water, as was everything in the universe. Thales’ idea was perhaps not as simplistic as it first seems, now modern science shows us that all matter can ultimately be reduced to energy.

. Anaximander and Anaximenes

One of the features of philosophy that distinguishes it from other ways of looking at the world is that its students are encouraged not to accept the conclusions of their teachers, but to discuss, argue, and even disagree. This is exactly what happened in the very first school of philosophy, the Milesian school founded by Thales: his student Anaximander asked if the Earth was supported by water (as Thales argued), then what supported that? He suggested that the Earth was a drum-shaped cylinder hanging in space, with one of the flat surfaces forming the world we live on.

Anaximander also had a pupil, Anaximenes, who said that the world was self-evidently flat and floated on air. Using the same sort of arguments as Thales, he concluded that the single element from which everything is made is air.

Although the conclusions of the Milesian philosophers seem to us hopelessly wrong in the light of later scientific discoveries, the process of reasoning used to reach them – especially argument and counter-argument – still forms the basis for philosophical investigation.

. Infinite regress

The argument Anaximander used to challenge his teacher’s theory of the Earth floating on water involved an idea that crops up in several strands of philosophy. If the world is supported by a body of water, then what supports the water? And then, what supports that? And so on, ad infinitum. The same pattern can be seen in arguments involving cause and effect: if something causes something else, then what caused that? This apparently unending chain is called an infinite regress.

Some philosophers saw the existence of infinite regress as proof that the universe is eternal, but many were uncomfortable with the idea and proposed that there must be an original or first cause for everything (an idea that chimes with the modern theory of the Big Bang). For some, the first cause or “prime mover” was an abstract idea akin to pure thought or reason, but, for medieval Christian philosophers especially, it was God: indeed, the idea of a first cause was at the heart of Thomas Aquinas’s cosmological argument for the existence of God.

. Heraclitus: everything is in flux

In contrast to the school of philosophy founded by Thales at Miletus, just along the Ionian coast in the city of Ephesus lived a solitary thinker, Heraclitus, with very different philosophical views. Rather than suggesting a single element from which everything was derived, he suggested an underlying principle – that of change. Heraclitus saw everything as consisting of opposing properties or tendencies, which come together to make up the substance of the world. The analogy he gave was that the path up a mountain is the same as the path down.

In this theory, known as the “unity of opposites”, the tension and contradiction of opposing forces is what creates reality, but it is inherently unstable. Therefore, everything is constantly changing: everything is in flux. Just as the water in a river is constantly flowing onwards, but the river remains the same, that which we consider to be permanent, unchanging reality consists not of objects, but processes.

. Pythagoras: a universe ruled by numbers

Pythagoras was born on the island of Samos off the Ionian coast, but unlike the other Ionian philosophers he apparently did not stay there for long. He is believed to have travelled around the Mediterranean, until, aged about 40, he set up a pseudo-religious sect in the Greek colony of Croton in southern Italy.

This eccentric genius had a particular talent for mathematics, making connections between geometry and arithmetic through the idea of squared and cubed numbers, and recognising mathematical ratios inherent in music and acoustics. He also brought this knowledge to bear on philosophical questions, arguing that there was a structure to the cosmos (a word he coined) based on mathematical laws. The positions and movements of the heavenly bodies, he suggested, were analogous to the ratios of musical harmony (the so-called “harmony of the spheres”).

Pythagoras was the first to connect mathematics and philosophy, and the founder of a distinguished line of philosophers, including Descartes, Leibniz, and Russell who were also great mathematicians.

. Xenophanes – evidence and true belief

Like Pythagoras, Xenophanes of Colophon was an Ionian-born philosopher who travelled widely, spending most of a reputedly long life moving from one Greek colony to another. His theory of cosmic composition involved two alternating extremes of wet and dry – neatly combining the Milesian ideas of pure elements of air and water with Heraclitus’s theory of opposites. What was more significant, however, was the fact that he used fossils to back up his idea that the world was once covered by water – one of the first examples of evidence-based argument.

Xenophanes is also credited with being the first philosopher to deal with the questions of epistemology, suggesting that when we say we “know” something, that knowledge is actually only a “true belief” – a hypothesis good enough for us to work from. A “truth of reality” does exist, but this will always be beyond our human understanding; the best we can do is refine our hypotheses to continually get nearer to it.

. Parmenides: monism

Around the beginning of the fifth century BCE, the centre of philosophy moved from Ionia to southern Italy, and in particular to the Greek colony of Elea. The founder of what became the “Eleatic school” was Parmenides, who produced a counterargument to Heraclitus’s idea that everything is in flux. Parmenides’s argument was based on the idea that you can’t say of “nothing” that it exists, and therefore there can never have been nothing: it cannot be true that everything came from nothing, so everything must always have existed – and will always exist since it can’t become nothing either. The universe, then, is completely full of something, which Parmenides believed was a single entity: all is one, uniform, unchanging, and eternal. This view is known as monism.

However, Parmenides was also at pains to point out that there is also a world of appearances – the illusory world in which we live. This distinction between reality and perception was to become an important idea in later Western philosophy.

. Zeno’s paradoxes

Like his mentor Parmenides, Zeno of Elea (not to be confused with Zeno of Citium) believed that “all is one” and that change is impossible. To support his arguments, he used paradoxes – examples that seem to be logically sound but reach a conclusion that flies in the face of common sense. For example, Zeno pointed out that, at any instant in time, an arrow in flight is in one particular place and therefore not moving; and since time is made up of successive instants in which the arrow is motionless, the arrow cannot be moving.

A different problem of motion is tackled in the paradox of Achilles and the tortoise: in a race together, Achilles gives the tortoise a head start, and they both start running at their different speeds. When Achilles reaches the point where the tortoise started, the tortoise has advanced a shorter distance ahead; by the time Achilles has caught up to this point, the tortoise has moved further on, and so on – so Achilles can never catch up with the tortoise, let alone overtake him.

. Sorites paradox

Many philosophers have found paradoxes useful, helping to clarify ideas by taking them to a logical, if absurd, conclusion. One of the best known is the “liar paradox” associated with Epimenides of Crete who asserted that “Cretans are always liars”. While some paradoxes can be shown to use invalid logical reasoning, others point to failings of logic itself. One example is the “sorites paradox” (from the Greek soros, a heap). One grain of sand is obviously not a heap, and nor are two grains of sand, or even three . . . and if we continue this progression then 10,000 grains don’t make a heap either!

The problem here is with our system of logic, where things are either true or false; it’s either a heap or not a heap, and there’s nothing in between. Another version of this paradox is that of the balding man – but here we can at least recognise various degrees of thinning. The shortcomings of “bivalent” logic can also be seen in other areas of philosophy, such as ethics, where it may be too simple to think in terms of right and wrong.

. The four elements

The question of what the universe is made of was still a major concern of Greek philosophers in the fifth century BCE. Empedocles, a native of Akragas in Sicily, continued the Milesian line of thought that everything was composed of a single element. But he took this a step further, identifying four distinct elements – earth, water, air, and fire – which, in different proportions, formed all the different substances in the universe.

Developing his ideas from the monism of Parmenides, he argued that these elements must therefore be eternal and unalterable, but reasoned that change was possible if some sort of force altered the mixture of elements. He suggested that two opposing physical forces, which he poetically called “Love” and “Strife”, caused attraction or separation of the elements and brought about changes in the composition of substances. His classification of the substances later known as the four classical elements was widely accepted by philosophers, and was a cornerstone of alchemy until the Renaissance. It influenced ideas such as the trinity of body, mind, and soul.

. Democritus and Leucippus: atomism

A theory of matter proposed by Leucippus and his pupil Democritus was less influential at the time than the “four elements” proposed by their contemporary Empedocles, but in retrospect seems closer to modern scientific understanding. They suggested that everything in the universe is composed of minute, unalterable and indivisible particles, which they called atoms (from the Greek atomos, uncuttable). These, they argued, are free to move through empty space, combining in constantly changing configurations.

The assertion there is such a thing as a void, an empty space, may be one reason these ideas were originally considered unacceptable. According to their theory, the number of atoms is infinite, and different kinds of atoms with different characteristics determine the properties of the substance they form together. Because the atoms are indestructible, when a substance, or even a human body, decays, its atoms are dispersed and reconstituted in another form.

. Athenian philosophy

In the fifth century BCE, Athens emerged as the major polis, or city-state, of mainland Greece. Already a significant military and trading power in the region, social and political reforms initiated by the statesman Solon led to Athens adopting a form of democracy in 508 BCE. The ensuing prosperity and security allowed a flourishing of culture in the city – especially in the arts of music, theatre, and poetry – and attracted intellectuals from other parts of the Greek world. Among them were Anaxagoras, from Ionia, and Protagoras, from Abdera in Thrace, who introduced the idea of philosophy to the city.

Athens was ideally suited to fostering philosophy and quickly became the centre of Greek philosophy, producing some of the most influential thinkers of all time. But more than that, Athenian cultural and political life influenced a change in the direction of philosophy, shifting emphasis from metaphysical concerns to the more humanist questions of moral and political philosophy.

. The sophists and relativism

Alongside the new democracy in Athens came a new legal system, and with it a class of advocates who, for a fee, would argue cases for clients or teach them how to use rhetoric and rational argument. Out of this class emerged a school of philosophers known as sophists, led by Protagoras, who used similar techniques to examine ideas of morality. Central to sophism is the idea (very much a lawyer’s stance), that there is more than one side to every argument, and we must take into account the perspective of the people involved.

For instance, the weather in Athens is clement to an Athenian, but seems hot to a visitor from Greenland, and cold to one from Egypt. This idea that there is no absolute truth and that there is only relative, subjective value, is known as relativism, and was summed by Protagoras as “man is the measure of all things”. Although this stance seems a reasonable one, the relativist approach does pose problems for moral philosophy: are there really no moral absolutes?

. Socrates and the dialectical method

The great philosopher Socrates was one of the foremost critics of sophism: he not only condemned their charging for wisdom, but also felt that philosophical enquiry should aim to elicit truth, not simply win a debate. However, this did not stop him adopting some of the sophists’ techniques of argument; having studied earlier philosophers, he realised that their method of reasoning was weak and based on speculation.

Socrates set out to rigorously examine fundamental questions through reasoned argument in dialogue with others of opposing views – a technique now known as the dialectical method. His approach was to start from the idea that “I only know that I know nothing”, and through discussion with a person or group try to arrive at agreed definitions. Starting with a seemingly simple question such as “What is justice?”, he would interrogate his subject relentlessly with further questions that exposed inconsistencies and contradictions, challenging assumptions and conventional beliefs in order to provide insights.

. Socrates and the origins of moral philosophy

It was not only in his methods that Socrates differed from most pre-Socratic philosophers; as an active participant in Athenian politics, he also felt their metaphysical speculations were largely irrelevant to human life. And despite his alleged contempt for the sophists, Socrates was as influenced by their concentration on human concerns as he was by their methods. What interested him were concepts such as justice, virtue, courage, and, above all else, truth – abstract ideas prompted by the structure of Athenian society, and what we now recognise as the concerns of moral philosophy.

In his philosophical discussions with the citizens of Athens, Socrates sought definitions for these concepts, trying to narrow down their properties by dialectical discourse and reasoning. He professed no knowledge or opinions, but his line of questioning often implied some underlying ideas of right and wrong and led the discussion to conclusions that he believed would help people to behave more morally and live a “good life”.

. The life unexamined

Socrates wrote nothing, founded no school, and had only a small group of followers, mainly young students. Yet he was well known in Athens for simply walking around the city engaging people in discussion, and was to become regarded as one of the greatest of all philosophers.

Not everyone appreciated his ideas at the time, however. Popular dramatists lampooned him as a figure of fun, while the establishment viewed him with suspicion for challenging conventional opinions. He was for a time dismissed as a sophist – a mere professional debater – but eventually he was accused of corrupting the morals of young people and not believing in the city gods. Tried and found guilty, he was offered the chance to renounce his philosophical enquiries to avoid the death sentence, but chose instead to drink the hemlock offered to him, saying that the life unexamined is not worth living. One of his followers, the young Plato, wrote a moving account of his trial and death in the Apologia, and through his other writings preserved Socrates’s ideas for posterity.

. Eudaimonia – the good life

At the heart of Socrates’s constant questioning was the question of how best we should live our lives. By trying to narrow down exactly what we mean by terms such as justice, virtue, honour, and courage, he believed people could learn to behave in a way that was more just, virtuous, honourable, or courageous, and live a good life. Of course, this in turn raised the question of what exactly we mean by living a “good life”, which the Greek philosophers called eudaimonia.

The search for a definition of eudaimonia and its attributes became a central concern of Greek moral philosophy. It seemed obvious that a “good life” should be a happy one, but by happiness do we mean contentment, or sensual pleasure? And what sort of lifestyle would bring about most happiness? For Socrates, the good life was about more than pleasure and happiness, and included the very ideals he examined in such detail: justice, honour, courage, and so on – all considered to be constituent parts of virtue, in its widest sense.

. Virtue and knowledge

As well as being professional advocates and orators, the sophists used their debating skills as educators. They not only trained their clients in rhetoric and argument, but also in ethics, in courses similar to those offered today by lifestyle coaches for legal professionals. What they taught was arete, which can be translated as “excellence”, but carries a notion of reaching one’s full potential.

The basis of arete played a central role in the concept of the “good life”, and was effectively synonymous with the Greek ideas of “virtue”. Socrates believed that to live a life of virtue, you have to know what arete is, and so reached the conclusion that virtue is knowledge. He argued that virtue is necessary and sufficient for the good life. Someone who does not know virtue cannot lead a good and happy life, and someone who knows virtue cannot lead anything other than a good and happy life. He summed this up in the apparently paradoxical statement “no one desires evil” – because virtue is knowledge, one can only do wrong out of ignorance.

. Beginnings of political philosophy

Perhaps because Athens had established a form of democracy that demanded the active participation of its citizens (or at least, a certain class of its citizens), Athenian philosophers soon began to apply the ideas of moral philosophy to society as a whole. Concepts of virtue, such as justice and freedom, were seen to relate not only to the individual, but also to the polis, the city-state.

This new field of ethics thus became known as politics – “things to do with the polis” – or political philosophy. Like the broader study of moral philosophy, its main concern for Greek philosophers was in defining the virtues appropriate to the state, but also included the idea of eudaimonia: how should an entire society be organised to best allow its citizens to live a “good life”? By extension, this involved an examination of the various ways in which a state could be governed, the means by which its laws could be made and enforced, and the relationship between the individual and the state.

. Plato and the Socratic dialogues

Since Socrates wrote nothing himself, almost everything we know about his philosophy comes from the works of his protégé Plato. Fortunately, nearly all of Plato’s prolific writings have survived, and Socrates figures largely in many of them. As well as accounts of Socrates’s ideas, such as the description of his trial in the Apologia, Plato embraced his mentor’s idea of the dialectic and presented a large number of his philosophical works in the form of dialogues. In most of these, Socrates appears as the principal character, quizzing other philosophers and public figures.

These “Socratic dialogues” present us with a problem, however. Plato is effectively putting words into the mouths of his characters – so how much of the philosophy underlying them is Socrates, and how much Plato? Luckily, Plato left us enough work that is clearly his own to get a good idea of his original ideas, but Socrates’s influence on him was enormous, and it is not always easy to distinguish the two.

. Plato’s theory of Forms

Socrates’s method of using dialectical questioning to establish the fundamental essence of a concept set Plato in the direction of one of his most important ideas, the theory of Forms or Ideas (given capital letters here to distinguish these from other meanings of the words). He, too, sought to find definitions, and find out what it is that makes a thing exactly the sort of thing that it is. When we see a bed, for example, we recognise it as a bed even though it may differ in many ways from all the beds we have ever seen. We have, Plato argued, an idea of an ideal Form of bed in our minds.

Similarly, we can recognise a circle, no matter how badly drawn, because we have in mind the Idea, or Form, of a perfect circle, even though such a thing cannot exist. There are also Forms for abstract concepts as well as concrete objects. These ideal Forms exist in a world separate from our earthly existence, but we have an innate knowledge of them that can be accessed by rational thought – in contrast to the imperfect perceptions available through our senses.

The regular geometrical shapes known as the Platonic solids were seen as some of the most perfect of all Forms – Tetrahedron, Cube, Octahedron, Dodecahedron, and Icosahedron.

. Plato’s cave

To illustrate his theory of Forms, Plato asked his students to imagine a cave, deep enough underground that no daylight reaches it, holding prisoners who have been chained all their lives so that all they can see is its back wall. Behind them is another wall, and beyond this a fire. People along the top of this wall, in front of the first, carry objects on their heads so that the shadows of these things are cast on the wall in front of the prisoners.

As this is all they ever see, Plato argued, the prisoners would assume that these shadows are the only reality, but if they could free themselves, they would discover they were mere shadows of reality. They would also find the light dazzling at first, and if they could make their way to the world outside the cave, would be temporarily blinded by the sunlight. If they returned to the cave, however, they would be unable to see because of the darkness. So it is with the illusory nature of our perception of the world compared to the world of Forms.

. Morality and religion

Philosophy developed from the human desire to find rational explanations for things without recourse to religion. The increasing sophistication of Greek society led to a feeling that, despite a still-widespread belief in the gods and their influence in the world, they had become more remote from human life. Most philosophers saw religion as irrelevant to their thinking, but with the emergence of moral philosophy the question of divine influence resurfaced.

Plato tackled this problem in his dialogue Eurthyphro, posing the question: “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because they love it?” In other words, is our morality determined by religion, or do we devise it ourselves and incorporate it into our religion? Plato took this further, suggesting that we have some innate concept (in his terms a knowledge of the Forms) of good and evil. This question of how far morality is human or God-given became a particular preoccupation for medieval Christian and Islamic philosophers.

. Plato vs Aristotle

In the early fourth century BCE, Plato founded a school of philosophy known as the Academy. Among his pupils was Aristotle, who had moved to Athens from Macedonia to study with him. Aristotle turned out to be as brilliant a thinker as Plato himself, but the two could hardly have been more different. While Plato thought in broad terms about abstract concepts, Aristotle was meticulous and practical; Plato’s ideas were based on a world of Ideas, Aristotle’s more down to earth.

As is almost invariably true of philosophers, their personalities are apparent in their approaches to philosophy. Plato and Aristotle held almost diametrically opposed views of how we understand and acquire knowledge of the world, which remained a basic division of schools of thought in epistemology until the 19th century. Despite their disagreements, they had a mutual respect for one another, and Aristotle remained at Plato’s Academy for about 20 years, only founding his own rival school, the Lyceum, several years after Plato’s death.

. Scientific observation and classification

Aristotle was both a keen naturalist and an almost obsessive organiser. After Plato’s death, he spent several years in Asia Minor studying the plants and animals. He identified characteristics, similarities and differences, and eventually produced a systematic classification of living things. Presented as a hierarchy from simple plants and animals to humans, it was later known as the scala naturae or the “great chain of being”.

Aristotle also took an interest in the physical science, or “natural philosophy”, and advocated the same methodical approach: observation, organisation, and a rational process of deriving conclusions. This was a radical departure from the pure reasoning promulgated by previous philosophers and a major step towards a scientific method of examining the world. He applied the same approach to his philosophy as a whole, organising and classifying his work in branches, but at the same time pointing out connections and building (probably) the first comprehensive system of philosophy.

. Aristotle: knowledge from experience

From his study of the natural world, Aristotle derived a theory of how we acquire knowledge that was diametrically opposed to that of Plato. He realised that what he knew about plants and animals had come through his observations and concluded that all knowledge came from experience.

For example, when he saw a dog, he could recognise it as a dog, even though dogs come in all shapes and sizes. Plato explained this as coming from an innate knowledge of a world of Forms (see above). But Aristotle reasoned that it was because he had seen a number of dogs before and gradually built an idea of what constitutes a dog from their common characteristics – from the various separate instances of “dog”, he had derived a concept of “dogginess”. In a similar way, we understand abstract concepts such as justice or virtue from our experience of various instances of them. Knowledge of anything is therefore empirical – it is only after experience of something via our senses that we can apply the process of rational thought.

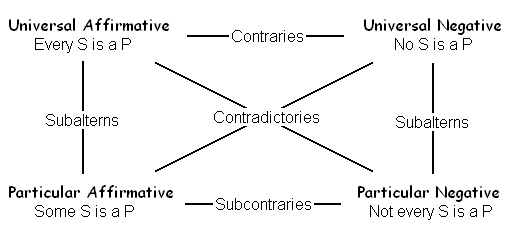

. Logic and the syllogism

Like all philosophers, Aristotle sought to justify his theories with rational arguments. But he was not content with the simple reasoning used by the early philosophers, nor even the dialectical method developed by Socrates. Instead, he proposed a system of logic whereby the information in two statements or “premises” can be used to reach a conclusion. For example, from the premises “All men are mortal” and “Socrates is a man”, we can infer the conclusion “Socrates is mortal”.

In the first formal study of logic, Aristotle broke down this form of logical argument, known as syllogism, into three parts: a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. Each of these parts contains two terms, presented in various forms such as “All A are B”, “Some A are B”, “No A are B” or “Some A are not B”. Using his talent for analysis and clarification, he then categorised the possible combinations of the different forms of premise and conclusion, identifying those that presented valid arguments, and those that were invalid.

. The four causes and the nature of being

Because of his practical disposition and interest in natural and physical sciences, Aristotle did not restrict himself to moral philosophy as much as Socrates and Plato had done. As well as examining the way in which we acquire knowledge of the world around us, he questioned what made things the way they are – the nature of being. He believed that we cannot have any knowledge of something until we understand its “why”: how it came to be, and in particular the explanation for change or movement of an object or event. Aristotle suggested four distinct categories of explanation, which he called “causes”, of how a thing has come about:

. material cause (the material the thing is composed of

. formal cause (the structure of the thing, or its blueprint)

. efficient cause (more akin to our modern understanding of cause, meaning the outside agency or event that brings it about)

. final cause (what a thing has come about for – its purpose or aim, but in a very wide sense).

Example:

A block of marble (material cause)

The idea of a finished statue (formal cause)

The sculptor (efficient cause)

Display on temple frieze (final cause).

. Republic and Politics

Both Plato and Aristotle extended their theories into political philosophy, examining how best society could be organised. Unsurprisingly, each took a different approach and reached a different conclusion. Plato’s Republic described his vision of a somewhat authoritarian city-state governed by specially educated philosopher-kings, whose knowledge of the Forms of virtue made them uniquely qualified to rule.

Aristotle applied a more systematic approach in his Politics. He analysed the possible forms of government, categorising them by criteria of “Who rules?” (a single person, a select few, or the people?) and “On whose behalf?” (themselves, or the state?). He identified three forms of true constitution: monarchy, aristocracy, and polity (or constitutional government). These all ruled for the common good, but when perverted, became tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. Given a choice, Aristotle believed that polity was the optimal form of government, with democracy the least harmful of the perverted forms.

. True constitutions for the common good

Monarchy

Aristocracy

Polity

. Perverted constitutions for the self-interest of a particular group

Tyranny

Oligarchy

Democracy

Aristotle’s classification of governments emphasises the importance of who governs and for who they govern. The correct forms aim for the common good, while the deviant forms serve the interests of the rulers. His insights into these forms of government continue to influence political thought and discussions about governance today.

. Ethics and the Golden Mean

Socrates was largely concerned with refining definitions of such things as virtues, in an attempt to discover their essential quality – a quest that continued in the moral philosophy of Plato and Aristotle. But although they apparently sought an absolute definition, they were wary of focusing it too narrowly, preferring to think of a sort of scale of degrees of each virtue. The idea of moderation figured largely in Greek thought from earliest times, encapsulated in the maxim “nothing in excess”, and exemplified in the ancient myth of Icarus (ignoring advice to take a middle course between sea and sky, Icarus was tempted to fly too high; the heat of the sun melted the wax of his wings and he fell to earth.)

Moderation was an especially important element of Aristotle’s ethics. He envisaged the spectrum of a virtue not as ranging from extremes of “good” to “bad”, but with an optimal value in the middle of the scale – the so-called Golden Mean. For example, courage is considered a virtue, but when taken to one extreme becomes recklessness and at the other extreme cowardice, both of which are undesirable traits; similarly, justice can be seen to have extremes of severity and leniency.

. Beauty

It was not only virtues that Socrates and his followers sought to define. One of his seemingly simple questions was: “What is beauty?” – the starting point for the field of aesthetics. As with virtue, it is easier to recognise individual instances of beautiful things than to pin down beauty itself.

For the classical Greeks, however, certain common characteristics could be identified, especially proportion, symmetry, balance, and harmony. These reflected both an interest in mathematics that had its origins in Pythagoras’s analysis of musical harmony and proportion, and the idea of the Golden Mean of Aristotle’s ethics. But in seeking a definition for beauty, other questions arose: are these criteria universal, or is beauty in the eye of the beholder and simply a matter of taste? Is something beautiful because we find it beautiful, or is there something inherent that makes it beautiful? And is there a difference between the beauty we see in nature and the man-made beauty of a work of art?

. Judging a work of art

Greek culture flourished in the classical period. In the time of the great Athenian philosophers, it produced great works of poetry, theatre, music, architecture, and art. Not everyone recognised their excellence, however – Plato, for example, distrusted all the arts as distracting and poor imitations of the ideal Forms of beauty and goodness.

But how then should we judge a work of art?

If we simply regard it as a matter of taste, we run the risk of confusing our emotional response with an objective appraisal, the so-called “affective fallacy.” It may be just as misleading to seek meaning in art: we may try to discover the artist’s intention, but find this at odds with our appraisal of his or her work. In the case of Wagner, for example, do his repugnant racism and personal arrogance detract from the worth of his music, or is this an instance of the “intentional fallacy”? Modern art often falls outside of our narrow definitions, and forgeries and reproductions challenge our perceptions of the role of the artist, raising the perennial question, “What is art?”

. Cynics: Diogenes

The trio of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle proved something of a hard act to follow. After them, Greek philosophy soon divided into four separate schools of thought – the cynics, sceptics, Epicureans, and stoics.

The cynics followed the thinking – and eccentric lifestyle – of Diogenes of Sinope, who took Socrates’s idea of rejecting conventional ideas of virtue to an extreme. Diogenes regarded desires for wealth, power, and honour as obstacles to virtue, preventing one from living a good and happy life. Instead, he advocated a simple life, free from material possessions and in harmony with human nature. This was no mere philosophical stance; Diogenes lived on the streets of Athens with no home except a discarded ceramic tub, wearing rags, scrounging food, and ignoring the norms of social custom and etiquette.

Like Socrates, Diogenes would accost Athenian citizens, but more critically; he was said to carry a lamp even in daylight “to help him find an honest man”. He was nicknamed “the Dog” for his lifestyle, and the word kynikos, dog-like, was adopted for the school of philosophy he founded.

. Sceptics: Pyrrho and his followers

It is in the nature of philosophical enquiry for assumptions to be questioned, but Pyrrho and his followers, the sceptics, made doubt the central principle of their philosophy. Like Plato, they believed that human senses cannot be relied upon, and therefore that we cannot know how things are, only how they appear. Consequently any evidence we have for an assertion, since it comes from our senses, is equally unreliable. This does not mean that it is wrong, but that it could be wrong or right. In logical argument, this meant that the truth of the premises is in doubt and can only be established by arguments based on other unreliable premises, ad infinitum: there can be no ultimate certainty. So, they reasoned, for every assertion, a completely opposing and contradictory assertion can be made with equal justification.

Scepticism can be seen as an extreme form of relativism, and in its purest form denies the validity of any philosophical argument. Despite this, it was to have a strong influence, especially on the philosophy of science and the logic-based philosophers of the 20th century.

. Epicureans

Despite the connotations of its name today, there was more to the Epicurean school of philosophy than simple hedonism. Although its founder Epicurus saw the “good life” as the pursuit of fulfilment and happiness, he regarded the goal of life as peace of mind and freedom from fear – in particular, the preoccupying fear of death.

Epicureanism was based on a belief that all matter, including our bodies, is composed of indestructible atoms. When we die, these are dispersed and re-form elsewhere; it is the end of our physical being and our consciousness, so is an end to both physical and emotional pain. Death, therefore, is nothing to be feared, and we should concentrate on enjoying life rather than fearing a non-existent afterlife.

Epicurus went further, questioning the relevance of gods, and even the existence of a benevolent god (although outright denial of the existence of god would have landed him in serious trouble). Inevitably, Epicureanism was quashed by later Christian and Islamic philosophers that followed, but many of its principles reappeared in modern scientific and liberal humanism.

. The immortal soul

Epicurus was probably the first philosopher to categorically deny that humans have an immortal soul. Working from the theory of atomism, he believed that not only is everything composed of atoms, but also there is nothing else – everything is material, and our physical death is the end of our existence. This was, and continued to be, a minority opinion.

Until the Enlightenment, most philosophers took the view that the senses and reason were separate, residing in the body and soul respectively. Plato saw evidence for the soul’s immortality in our innate knowledge of the world of Forms, which he suggested was remembered from previous existences. Aristotle also argued that although we gain knowledge through senses that disappear when our bodies die, the soul is responsible for our thoughts and can exist without a body; because it is immaterial, it cannot be corrupted and is therefore immortal. Belief in an immortal soul is essential to most religions, and a cornerstone of Eastern philosophy.

. Stoics: philosophy of the Roman Empire

The last school of philosophy to emerge in ancient Greece, stoicism, evolved from the notion of virtue residing in simplicity and human nature proposed by the cynics. Zeno of Citium (not to be confused with Zeno of Elea), founder of the stoic school, taught that nature is the only reality, and that we are a part of it. Using our capacity for reason, we must learn to accept things we have no control over and also to control our destructive emotions. Virtue alone is sufficient to ensure the happiness of a “good life”, and anybody who has knowledge of virtue and leads a virtuous life will not be affected by any misfortunes that befall him.

The development of stoic philosophy coincided with the decline of Greek political and cultural influence and the rise of Roman power. The Romans, not previously known for their enthusiasm for philosophy, found stoicism fitted comfortably with their own culture of ethics, and it became the prevailing philosophy of the Roman Empire, adopted by thinkers including Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius.

Eastern philosophy

Until quite recently, Western philosophy developed in isolation from the traditions of China and India. The division between religion and philosophy was less clear-cut in the East, where adherence to a religion involved acceptance of its moral philosophy, and philosophy assumed belief in a religious, or at least unsupported, metaphysical explanation.

The first great Eastern philosophers, such as Laozi and Confucius in China and Siddhartha Gautama in India, were roughly contemporary with the first Greek philosophers. Their emphasis on morals, however, anticipated Athenian philosophy. In some respects, their conclusions were strikingly similar, but with the arrival of Christianity, Eastern and Western philosophies became marked by differences rather than similarities.

In the 19th century, some Western philosophers “discovered” Indian religion and philosophy, and realised the similarity to the views of German idealism in particular.

More recently, the religious aspects of Eastern philosophies have taken precedence, while philosophical thinking in the East has come under Western influences.

. Daoism

One of the primary concerns for the dynastic states of China in the sixth century BCE was to establish a system of government that reflected traditional religious ideas. A class of scholars with civic responsibilities had emerged, and among them was Laozi (or Lao Tzu), who proposed a comprehensive moral philosophy as a basis for social and political organisation. This view of the world subsequently became known as Daoism. Laozi started from a belief that the ever-changing world was made up of complementary states: light and dark, night and day, life and death, each arising from the other in a cyclical fashion and in eternal harmony and balance.

These “10,000 manifestations” form the process of change known as dao, “the way”, characterised by “not-being” and beyond human understanding. We disturb the cosmic balance if we stray from the dao by giving in to desire, ambition, or social convention; to live in accordance with the dao, we must adopt a life of “non-action”, a simple and tranquil life in harmony with nature, behaving intuitively and thoughtfully, not impulsively.

. Confucianism

Kong Fuzi, known in the West as Confucius, was of the generation following Laozi, and may have consulted him in his capacity as court archivist. While Laozi had outlined a moral philosophy, Confucius was concerned with providing a political structure that would allow a stable but just government. This, he argued should be based on virtue and benevolence but, contrary to conventional belief, he thought moral goodness was not god-given, nor restricted to any particular social class. Instead, he believed that virtue could be cultivated, and that it was the ruling class’s role to lead by example. The junzi, or “superior man”, by making his virtue manifest, would inspire virtue in others, which could be reinforced by ceremony, ritual, and societal niceties. This could best be achieved by a hierarchical society in which faithfulness was the guiding principle: a ruler should be benevolent, and in return his subjects would show loyalty. Confucius extended this reciprocal faithfulness to other relationships – between loving parent and obedient child, husband and wife, siblings, and friends and colleagues.

. The Golden Rule

The idea of reciprocal respect as a model for human relationships is central to the moral philosophy of Confucius. He also advocated reciprocity as a guide for our behaviour towards others: “what you do not desire for yourself, do not do to others”. Interestingly, Confucius presents this “ethic of reciprocity” in a negative form (as do many Eastern religions), implying restraint rather than action, while in the West it is more familiar as the positive “do unto others as you would have them do unto you”. In one form or another, this maxim has featured in almost all major religions, and has been stated by many moral philosophers. Because of its universal acceptance, it has become known as the “Golden Rule”.

The concept is not only fundamental to ideas of ethics, but also has implications for political philosophy. Incorporating the principle into a system of government raises questions of how much its rule should impinge upon the lives of its citizens – how authoritarian or libertarian it should be.

. Samsara, dharma, karma, and moksha

Many different religious traditions arose among the early civilisations of India but most had certain concepts in common. Now known collectively as Hinduism, these religions shared a belief in reincarnation – a cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth, called samsara. Along with this came a belief that liberation from this cycle can be achieved by leading a good life, so that a moral philosophy was an intrinsic part of religion.

The immortal soul, atman, is reborn in many forms according to karma, the moral law that rules the universe and determines action and reaction. The ultimate aim of life is moksha, release from the cycle of birth and rebirth, by devotion to God, but also through knowledge of karma, and especially through dharma, appropriate action. The idea of dharma, the duties and ethics necessary for leading a good life, provided a complete moral philosophy in many ways similar to that of the Greek philosophers, but inextricably connected with a religious explanation of the universe.

. Buddhism

Siddhartha Gautama, later known as the Buddha, was born in India in the sixth-century BCE and brought up in the religious tradition of belief in a cycle of birth and rebirth. He gave up his comfortable background and adopted an austere lifestyle in a quest for release from this cycle, but realised this was not leading to a life of fulfilment either. He reasoned there was a “middle way” between the extremes of sensual pleasure and asceticism (anticipating the idea of the Golden Mean, see above).

Life is characterised by suffering, caused by unfulfillable desires. We can avoid this suffering by overcoming our egos and giving up “attachments” to worldly power and possessions. He summed this idea up in the Four Noble Truths: those of suffering, of the origin of suffering, of the end of suffering, and of the “Eightfold Path” to the end of suffering.

By following the Eightfold Path (right mindfulness, right action, right intention, right livelihood, right effort, right concentration, right speech, and right understanding), we can lead a life of fulfilment and escape the cycle of rebirth to achieve a state of nirvana.

Christianity and philosophy

The doctrines of the Christian Church dominated the philosophy of medieval Europe. Christianity, especially in its early period, placed less emphasis on philosophical reasoning and more on faith and authority. Philosophy was regarded with suspicion, and the ideas of the Greek philosophers were initially considered incompatible with Christian belief.

The Church had a virtual monopoly on scholarship, but some Christian thinkers introduced elements of Greek philosophy – especially that of Plato and Aristotle. After careful examination by the authorities, many of these were gradually integrated into doctrine. From the end of the Roman Empire to the 15th century, a distinct Christian philosophy evolved, starting with Augustine and culminating in the comprehensive philosophy of Thomas Aquinas.

With the Renaissance, however, the authority of the Church, and the papacy in particular, was challenged by a resurgence of humanist views. Scientific discoveries contradicted core beliefs, and the invention of printing meant the Church could no longer control access to information.

. Reconciling faith and reason

The first significant Christian philosopher was Augustine of Hippo. Although his mother was a Christian, he at first rejected the faith and studied philosophy, engaging for a while with the Persian religion of Manichaeism. It was only after a thorough study of Greek philosophy, and especially Plato and the “Neo-Platonism” taught by Plotinus, that he converted.

Unsurprisingly, his approach to Christianity, was coloured by his philosophy. He believed the two were not incompatible: Christianity is characterised by belief, philosophy by reasoning – but, he argued, faith and reason can not only coexist, but are complementary. He suggested that Christianity could absorb the philosophy of Plato without contradicting any of its central beliefs, in order to provide a rational basis for its theology. His work coincided with the adoption of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire, and in his book The City of God he explained how it was possible to be a citizen of an earthly community at the same time as living in the eternal and true world of the kingdom of God – an idea adapted from Platonism.

. Existence of God: the teleological argument

A recurrent concern for medieval Christianity was whether there could be a philosophical, rational proof of God’s existence. While many in the Church believed this to be simply a matter of faith, the incorporation of philosophy into religion encouraged rational justification. Several arguments for God’s existence were put forward, including the so-called argument of design, or teleological argument (from the Greek telos, purpose). The reasoning goes that if we look at the world around us, we see evidence of order. Everything looks as if it has been designed for a purpose, and if everything has been designed, then there must have been a designer – God. The argument, developed from ideas in Plato and Aristotle, appears not only in Christian philosophers such as Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, but also in the work of the Islamic philosopher Averroes. Later philosophers challenged this premise, questioning the notion of purpose and replacing it with cause, while scientific advances, in particular the theory of evolution, have helped to refute the argument.

. The problem of evil

Christian philosophers not only sought a rational argument for the existence of God, but also had to deal with opposing arguments. One of the most powerful, proposed by Epicurus, raises the problem of the existence of evil. In the Epicurean paradox, he asks: “Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then why is there evil in the world? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?”

Augustine, the first Christian philosopher to address this paradox, argued that God gives us the freedom to choose whether to do right or wrong. Although God created everything that exists, he did not create evil, as evil is not a thing but a lack – a deficiency of good that came about as a result of man’s rationality, given to us when Adam chose to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge. Evil is therefore the price we pay for God allowing us free will – although this in itself raises further questions of God’s omniscience.

. Free will vs determinism

According to Christian belief, God allowed Adam the freedom to choose whether to eat the forbidden fruit. Although He is omnipotent, He has given us free will to decide our actions. But He is also omniscient. And if He knows what we are going to do, then our actions must be predestined, so how can we be said to have free will? The early Christian philosopher Boethius answered this by explaining that God’s knowledge of our future actions does not prevent us from being free to make a choice. God foresees, but does not control, our thoughts and actions.

This problem has continued to occupy philosophers. On the one hand, there is determinism, the belief that everything that happens is determined by conditions so that nothing else could happen; on the other, the libertarian belief that we are free to choose our actions, and free will and determinism are incompatible. Somewhere in between are those who believe that our choices are determined but our decisions are our own – we are free to play the hand that we are dealt.

. The Consolation of Philosophy

Around 524 BCE, the Roman philosopher Boethius offered his thoughts on the problem of free will in his book The Consolation of Philosophy, written while he was in prison awaiting execution on charges of treason. He presents his ideas as a conversation with Philosophy personified, who offers her wisdom to console him. They discuss virtue, justice, and human nature, as well as free will and predestination – the same subjects that concerned classical Greek philosophers.

Boethius was a Christian, and the book deals with many matters of faith, but it is significant that he found consolation in philosophy rather than religion. At this period, Christianity was beginning to assimilate philosophical ideas into its doctrine – philosophers such as Augustine and Boethius represented both the end of classical philosophy and the beginning of this process. That there was a place for philosophy in Christianity was confirmed by the continued influence of Boethius’s work throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

. Scholasticism and dogma

The Catholic Church wielded considerable social and political power in medieval Europe, and also controlled access to learning. Education was provided by the Church and necessarily followed Christian doctrine, while libraries and universities were funded by the Church and staffed by monastic orders. Monks preserved and translated many ancient texts, mostly of Greek philosophy and latterly acquired from Islamic scholars.

Scholasticism was a method of tuition that used rigorous dialectical reasoning both to teach Christian theology and to scrutinise these texts. Clerics and academics used methods of reasoning developed by Plato and Aristotle to assess the compatibility of ideas with Christian doctrine.

The theories of philosophers including Augustine and Thomas Aquinas were also examined, and either adopted to defend Christian dogma or dismissed as heretical. Scholasticism played an important part in the integration of philosophical ideas into Christianity, remaining the predominant ethos for Christian education and theology until supplanted by humanist ideas in the Renaissance.

. Abelard and Universals

Today, Peter Abelard is best known for his illicit love affair and secret marriage to Heloise, which brought about the end of his academic career. But this overshadows his role as one of the most influential Christian thinkers of the 11th century.

Abelard was a prominent scholastic philosopher, well versed in Aristotelian logic. He shared Aristotle’s rigorously systematic character, and was sceptical about the Platonism that had become absorbed into Christianity. The prevailing view, realism, was based on Plato’s theory of Forms (see above), and maintained that the properties things have in common – the “blueness” of both a cornflower and the sea, for example – exist independently as “Universals”. Abelard, however, took Aristotle’s view that the common property is inherent in its particular instances, and argued that the Universal only exists in our thoughts – a concept, not a reality.

Abelard’s theory, which became known as conceptualism, initially met with opposition, but spearheaded a movement to incorporate the ideas of Aristotle, as well as Plato, into Christian theology.

. Existence of God: the ontological argument

With the rise of scholasticism and Christianity’s embrace of Aristotelian logic in the 11th century came a renewed interest in reconciling matters of faith with reasoned argument. One of the founding fathers of the scholastic movement was Saint Anselm, best known for proposing the so-called ontological argument for the existence of God.

Anselm asks us to imagine the most perfect being possible. If such a being does not exist, however, it cannot be the most perfect possible and must be inferior to one of the same perfection that does exist. So, the most perfect being possible must exist – in Anselm’s words: “God is that, than which nothing greater can be conceived”. As a logical argument, however, this is flawed, and contemporaries such as Gaunilo of Marmoutiers pointed out that it could be used to prove the existence of anything. Later philosophers, notably Thomas Aquinas, and later still Immanuel Kant, showed that while the argument presented a notion of God’s essence, it was no proof of His existence.

The ontological argument

God is the greatest thing in the universe

But what if God doesn’t exist?

In that case, He’s not really that great

So, if he’s really the greatest thing in the universe, then he must exist!

. Pascal’s wager

Today, it is generally agreed that there can be no logical proof either way for the existence of God, and that this is purely a matter of faith. Philosophical speculation on the subject, however, continued well into the so-called “Age of Reason”. One novel take on the problem was raised by the mathematician Blaise Pascal in the 17th century.

“Pascal’s wager” examines whether, given that we can have no proof of His existence, it is a better bet to believe in God than not. Pascal weighs up the pros and cons in terms of the consequences: if God exists and I deny his existence, I run the risk of eternal damnation; if He exists and I accept His existence, I earn eternal life in paradise; but if he doesn’t exist, it will make no difference to me. On balance, then, it is a safer bet to believe in His existence.

Although Pascal’s wager is an interesting exercise in logic and rudimentary game theory, it is based on some shaky premises – we are asked to assume that God bases His decision on my afterlife on my belief in Him, that He, too, is a rational being and that heaven and its polar opposite also exist.

. Thomas Aquinas

Probably the greatest of medieval Christian philosophers, Thomas Aquinas’s major achievement was to synthesise the apparently contradictory philosophies of Plato and Aristotle and show they were complementary to Christian belief. From Plato’s view of Universals in his theory of Forms, he derived the notion of what he called the essence of things. This, he said, was distinct from its existence: for example, it is possible to describe the attributes of a dragon – its essence – yet still deny its existence. He further argued that since God created everything according to his design, the essence of things must precede their existence. But he also believed that our minds are like a clean slate, or tabula rasa, and took from Aristotle the idea that we acquire knowledge through our senses. While careful to distinguish such ideas from questions of faith, Aquinas did not see them as incompatible. These rational explanations concern the way we learn about the world, but we can still believe it to be God’s creation. Inevitably, it took some time for such ideas to be accepted by the Church.

. Existence of God: the cosmological argument

Thomas Acquinas used his ideas of essence and existence to refute Anselm’s ontological argument for the existence of God (see above).

Instead, he proposed a stronger argument, known as the cosmological argument, derived from Aristotle’s notion of causes. In brief, he argued that something must have caused the universe to exist, a First Cause, and this is what we call God. As explanation, Aquinas says that although the universe obviously exists, it is conceivable that in other circumstances it might not exist; its existence is therefore contingent on a cause. This has to be something that cannot conceivably not exist, and is not contingent on anything else – an uncaused cause. This, Aquinas says, we understand to be God.

The similarity of the cosmological argument to the scientific Big Bang theory is striking, and both involve the philosophically problematic acceptance of a first, uncaused, cause. However, refuting it by denying the possibility of an uncaused cause involves the equally difficult problem of infinite regress (see above).

. Natural Law

Christian philosophers could base their moral philosophy on the teaching of Jesus, but extending this to political philosophy raised the question of how far the laws of man were compatible with the law of God. Augustine tackled the issue in The City of God, contrasting earthly society and the kingdom of God in a similar way to Plato’s worlds of appearances and Forms. Taking the idea further, Thomas Acquinas suggested that human laws were separate from God’s eternal laws but that there also exists a Natural Law, based on human behaviour, morals and virtues, that is a part of God’s law.

An important part of Natural Law was the concept of “Just War”. Christianity (and many other religions) preaches pacifism, but politics sometimes makes war necessary. Rather than being a contradiction of God’s law, however, Aquinas suggested that war could be justified by Natural Law. Again basing his ideas on Augustine, he proposed three requirements for war to be just: rightful intention, a just cause, and authority of the sovereign.

. Acts and omissions

In common usage, “ethics” refers to how we judge the morality of our actions. At the heart of any judgement we make of an action are two things: the consequence of that action, and the intention of the person making it. While the seriousness of the consequences provokes our immediate reaction, with further thought we realise that intention is crucial to deciding morality. Is a deliberate theft less morally defensible than a fatal mistake? Moral judgement is simple when both intention and consequences are bad, but not so easy to decide when serious consequences are a result of good intentions, or at least without bad intention.

Further dilemmas arise when deliberate choices have to be made. Sometimes a sacrifice has to be made for “the greater good”; there are cases where several lives can be saved by the deliberate loss of another, for instance. But do the ends always justify the means? And is there a moral difference between deliberate action and deliberately allowing something to happen?

Example (?): A runaway train is out of control and hurtling towards a final set of points. Should the signalman take action by diverting the train onto a sideline where a group of workmen will be killed, or is he morally less culpable if he takes no action and allows the train to speed on and ultimately crash in the station, killing many more people?

. Nominalism

Because Plato’s philosophy had been firmly assimilated into Christian doctrine from the time of Augustine, the introduction of Aristotle’s contrasting ideas met with some resistance. Scholastic philosophers adopted a rigorous Aristotelian methodology, but his views on the problem of Universals (see above) were seen as contradicting Church teachings.

Peter Abelard was among the first to challenge the idea of realism (that the Universals have a real, independent existence) with his idea of conceptualism (that they exist only in our minds). Thirteenth-century philosophers such as John Duns Scotus and William of Ockham went further, arguing that the Universals did not exist at all, except as names referring to properties of things in the real world. For Duns Scotus, the Universals were simply adjectives used to describe these real-world objects. Unlike Aquinas’s synthesis (see above), this “nominalist” idea directly contradicted realism. Christian philosophy split into opposing schools of thought on the issue – a division echoing differences between Plato and Aristotle, which persisted well beyond the Renaissance between continental rationalists and British empiricists.