– Politics has played a key role in human communities throughout history. It affects every decision about how societies should function and who should lead them.

INTRODUCTION

Human beings have always lived in communities throughout society and, because of that, politics has always been with us. It is primarily a social activity – one that is concerned with how societies are organised, and how they might be changed for the better. Yet, it is also a theoretical discipline – one that tries to answer questions such as: How is political authority justified? How much power should a government have over its citizens? What rights do citizens have, and how should they be protected?

The answers to these questions have always been disputed, and they can be grouped together into what are known as “ideologies”. An ideology is a tradition of thought, and it may favour autocracy (absolute rule by one person), or democracy (rule by the people), or something in between, such as an elected monarchy. What distinguishes these ideologies from one another is that each offers a fundamentally different view of human nature. For example, defenders of autocracy, or of extensive government powers, tend to view humans as being inherently violent, and in need of state control. On the other hand, defenders of democracy, or of limited government powers, tend to view humans as being inherently reasonable, and capable of controlling their own destinies.

This page aims to provide an overview of the main political ideologies and will examine the range of institutions that governments use to implement their policies. Just as there are different kinds of authoritarian regimes, there are different kinds of democracies, all of which will be analysed on this page. The first few sections look at political theory, how governments are organised, and some of the problems governments face – such as how they should interact with each other internationally, and how they should manage resources at home. Later, there will be an overview of the main governments of the world today, with a focus on what makes each of them unique.

1. Foundations of Political Thought

a). The need for politics

Humans are social animals and have evolved with the natural tendency to live in social units. In order to operate successfully, these units – or societies – have had to develop ways to organise and regulate themselves for the benefit and security of their members. As a result, various forms of government have emerged. The process of establishing these distinct systems and deciding how they should operate is the business of politics.

Rulers and citizens

Throughout history, the government of society was determined by a ruler, or ruling class, and ordinary citizens had no say in the matter. Then, during the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries, philosophers began to consider the relationship between government and those being governed, and suggested ways in which citizens could be involved in selecting their rulers.

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) – English philosopher Thomas Hobbes felt that without authority society would fall into anarchy. He argued that people should submit to a sovereign ruler with absolute power.

Jock Locke (1632–1704) – English philosopher John Locke believed society should transfer some of its rights to the government in order to ensure the people’s right to their life, liberty, health, and possessions.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) – Swiss-born philosopher Rousseau argued that all the existing forms of government were based on inequality. He said that the power to make laws should be in the hands of the people.

Growth of civilisations

Since prehistoric times, humans have banded together. Early family groups of nomadic hunter-gatherers merged into clans and tribes. Later, the adoption of agricultural practices necessitated permanent settlements. These grew in size and sophistication from encampments and villages to towns and cities, and extended their influence into surrounding territories, either to ally with or conquer other cities. The world’s great ancient civilisations emerged from these so-called city-states, as they increased their power to become kingdoms or even empires, and the precursors of modern states. As these societies evolved, they developed varying forms of political organisation, coming up with different notions of how to rule and govern the populace.

“The administration of justice… is the principle of order in political society.” – Aristotle, Greek philosopher, Politics, Book I (4th century BCE)

b). The ruler is sovereign

In his book Leviathan, a key work of political philosophy written in 1651, Thomas Hobbes presented his argument that a powerful ruler is necessary in order to control conflict in civil society.

Anarchy and unrest – Thomas Hobbes wrote Leviathan during the English Civil War (1642–51), an event that strongly influenced his political philosophy. His experience of the conflict left him with a pessimistic view of human existence: life for most people, he said, was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”. He believed the war arose from disagreements in the philosophical foundations of political knowledge. He devised his own reformed theory of how people might be best governed in order to bring an end to divisiveness, and also to end the conditions of war. Without regulation of some sort, Hobbes reasoned, it would be every person for themselves in a fight for survival. This scenario, the philosopher believed, would result in a constant state of chaos, just as in the Civil War.

Hobbes believed that political authority existed in order to avoid such disorder. In return for citizens sacrificing some of their liberties, their rulers would protect them from attacks by others.

A greater good – Hobbes explained the concessions made by each individual in favour of society as a whole, as a form of agreement – or “social contract”, as it later became known. In forming such a contract, society itself is made into a sovereign authority, to which the individuals surrender their own authority.

In order to prevent society descending into anarchy, Hobbes argued that this sovereign authority must be strongly enforced – and the job of enforcement is granted to the sovereign ruler. The ruler is given absolute power, taking control of all civilian, military, and judicial matters. In return, it is the sovereign’s duty to ensure the protection and well-being of the population.

The philosophy of Thomas Hobbes

Hobbes was a materialist, meaning he believed that everything in the universe is physical. He therefore denied the existence of immaterial substances. As an extension of his materialism, Hobbes argued that the universe and everything in it behaves in a mechanistic way, according to scientific laws, and as a result he rejected the idea that humans have free will. He also believed that people are, by nature, motivated by self-interest in order to satisfy their physical needs. Hobbes was the first of the philosophers to promote the idea of the social contract.

The Sovereign – According to Hobbes, people are only able to live in peace and prosperity if there is “a common power to keep them all in awe”. This, he proposed, should be a sovereign ruler who is given absolute power, and under whose leadership the people are united.

Conflicts of interest – In any social group, there will inevitably be conflicts of interest and disputes over resources and ownership. The function of civil society is to prevent and resolve these conflicts, and to do so requires some form of government.

The state of nature – Without the constraints of civil society, Hobbes argued, peoples’ natural state or “state of nature” would be one of constant conflict for supremacy and survival.

The social contract – is a theory that argues for the authority of the state over the individual. The phrase was coined by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in 1762; however, Hobbes proposed the idea more than a century earlier.

c). Sovereignty by consent

An influential supporter of the core Enlightenment values of liberty, equality, and rational thought, John Locke advocated a society based on a social contract that protects the “natural rights” of its members.

The people’s rights – John Locke held a more favourable opinion of human nature than Thomas Hobbes, believing that people are essentially cooperative, altruistic, and, above all, rational. Locke acknowledged that people would also want to protect their own interests and explained that each individual has a “natural right” to defend their life, health, liberty, and possessions. He further recognised that this could lead to conflicts of interest but proposed an alternative way to resolve these.

Whereas Hobbes had advocated a strong sovereign authority in order to prevent conflict, Locke favoured a more benign form of rulership. He argued that a successful civil society required the people to grant a government authority to rule over them. This would ensure that the government in turn protects, rather than restricts, its people’s rights and freedoms. Locke believed that the core function of such a government is to secure justice by acting as an arbiter in any disputes, and to respect the natural rights of each citizen. He argued that if any government failed to do this, the people could overthrow it, replacing it with one that serves their interests.

Enduring influence – In Locke’s opinion, as people are both rational and cooperative, they would consent to the government exerting authority over them to secure their natural rights. This interpretation of the social contract, as well as Locke’s concept of an individual’s rights, influenced liberal thinkers in 18th century Europe. It had an impact in the US, too: Locke’s theory of rights is the source of the right to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness”, as cited in the US Declaration of Independence.

“The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom.” – John Locke, Second Treatise of Civil Government (1690)

The Enlightenment – During the 17th and 18th centuries, an intellectual movement known as the Enlightenment took hold of European society. Scientists and philosophers emphasised the importance of rational thought and science over faith and religion, challenging the authority of both the Church and the monarchy.

The Enlightenment forced people to re-examine the way that society was organised and governed, and prompted a political movement centred on the ideals of liberty, equality, and the rights of citizens that culminated in the American and French revolutions.

Government by consent – Both Hobbes and Locke identified that the formation of a civil society is dependent on a form of social contract, in which the people agree to give power to the government in return for their security. Locke, however, stressed the element of consent necessary in such an agreement. The people, he argued, willingly submit to the rule of a government that will protect their rights and administer justice in disputes over conflicts of interest.

Rational and cooperative – Locke’s vision of civil society was based on the idea that people are naturally social animals who are capable of reasoning. Humans understand the advantage of behaving cooperatively in social groups without coercion, rather than as selfish individuals.

The social contract – Although each individual has natural rights, these can only be protected by society as a whole, with the people’s agreement. As members of civil society, citizens effectively enter into a social contract with the government, surrendering some autonomy and granting authority to the government.

Supporting state systems – Under the terms of the social contract, members of civil society grant a government the authority to exercise power on their behalf, for the benefit of society as a whole. The agreement may be formalised in a nation’s constitution, detailing the powers and responsibilities of the government and the rights of its citizens.

d). The people are sovereign

Jean-Jacques Rousseau criticised the concept of civil society, claiming it corrupts humanity’s innate goodness and restricts freedom. Instead, he advocated a society governed by the “general will” of the people.

Society corrupts – Rousseau coined the term “the social contract” when he used it as the title of his influential political treatise, published in 1762. But his vision of how this would work in an ideal society was fundamentally different from the concept formerly envisaged by Hobbes or even Locke.

Rousseau argued that in a state of nature, humans are essentially good as well as free: because natural resources are available to all, there are no conflicts of interest. As he explained, “the fruits of the earth belong to all, but the earth itself belongs to nobody”.

What spoils this ideal situation, according to Rousseau, is when a person claims a territory as their own, denying others access to its resources. In the past, civil society had protected the rights of the individual, especially the right to private property. In doing so, it created inequality and restricted freedom, fostering conflict, and a corruption of people’s natural goodness. Conflicts of interest were then inevitable between those who had and those who had not.

Power to the people – Rousseau’s solution was a radically different form of society and the social contract: instead of people granting a government authority, as Locke had proposed, society should instead by governed by the people themselves. Rousseau argued that decisions should be made by consensus, expressing the “general will” of the people. This would ensure that a government preserves the interests of society as a whole – rather than just protecting individual rights – therefore restoring the natural freedom of the people.

The “general will” – In Rousseau’s ideal society, the focus is on the collective interest of the citizens, as opposed to the rights of the individual. Government should be a collective process, with people engaging directly in democracy, rather than through representatives.

Private property creates inequality – Claiming ownership of private property leads to unfair distribution of resources, and a government that protects the right to property restricts natural freedom.

Society governed by citizens – Rather than giving authority to a government, the people should be sovereign, with decisions made according to the wider will of the citizenship as a whole.

Each member is an indivisible part of the whole – Every citizen forfeits individual rights but is an integral part of society. As the general will serves to protect individual freedoms, an attack on the rights of one is an attack on all.

Rousseau and the French Revolution – Just as Locke’s theory of rights inspired the ideals of the American Revolution (1775–83), Rousseau provided similar inspiration in France. The French Revolution (1789–99) shared the same aspirations for the rights of citizens as the newly established American Republic, but it was Rousseau’s ideas of freedom and equality, and of overthrowing the corrupt old order, that fired up the revolutionaries. Their rallying cry of “Liberté, égalité, fraternité”, later adopted as a motto of the French Republic, was a direct paraphrase of the ideas set out in Rousseau’s The Social Contract.

e). Who should rule?

Different models for ruling over a population have evolved over time, along with ideas around how best to serve the interests of those being governed. Old models of leadership by a single ruler, who most likely inherited power, supported by a privileged caste, have largely been replaced by systems that are increasingly democratic. In the modern world, most countries favour governments that are elected by the people to represent the views and aspirations of the people.

Why do we need leaders? – Humans are, by nature, inclined in wanting to be led. Even in democracies in which people are “equal”, leaders still emerge. Some are no more than figureheads, but often a single person is elected to take final responsibility for the actions of the government. Only a few political systems, such as anarchism, do not regard leaders as a necessity.

Tony Benn, in his last speech in the House of Commons as a British politician in 2001, expressed a comprehensive overview of the question ‘Who should rule?’ He said:

“[1] What power have you got?

[2] Where did you get it from?

[3] In whose interests do you exercise it?

[4] To whom are you accountable?

[5] How do we get rid of you?”

Types of leader – Government leaders reflect the different political systems of the societies they represent, as well as that society’s values and priorities. The selection process for leaders varies between societies: leaders may be given power out of respect, some are born to power, some seize power, and others are appointed or elected.

Tribal – Smaller tribal societies are structured like traditional families. Tribal leaders are the head of the family, providing security and protection. They are often chosen for their seniority, wisdom, and experience.

Military – Military leaders may attain power because of their skill in battle or their seniority in rank. In the past they have seized power through conquest; these days it is more likely to be as a result of a coup d’état.

Hereditary – Historically, many nations have been ruled by monarchs – kings, queens, emperors, sultans, emirs – who were believed to have inherited a divine right to rule, which they passed to their heirs.

Religious – In strictly religious and pious societies, the laws and government are thought to be divinely determined and are controlled by priests or officials of the main religion. Leaders are chosen for their moral authority and religious knowledge.

Elected – In the modern era, the ancient idea of democratic rule has come to dominate. Leaders can be directly elected by the people or by elected representatives. It is rule by the people rather than by an individual.

f). Wise leaders –

Throughout history, some rulers have inherited their power or seized it by force, while others have been chosen for their leadership qualities, especially the traditional values of wisdom and experience.

A ruling class – It may seem obvious that one of the qualities of a good ruler is wisdom, but it was the Athenian philosopher Plato (5th century BCE) who identified the specific kind of wisdom he believed necessary in a leader. In his book Republic, Plato described what he considered to be an ideal society, and how it should best be governed.

Plato saw society as consisting of three classes of people: the ordinary working people, the armed forces, and the educated elite. He had experienced rule by “ordinary people” in the form of Athenian democracy, under which his friend and mentor Socrates was accused of corrupting the city’s youth with his ideas and sentenced to death. From this, Plato concluded that it was the educated and wise who were best suited to rule because they would be guided by reason, rather than self-interest.

Philosopher kings – In Plato’s ideal society, people are able to live the “good life”: they are safe, happy, and behave moralistically. It is the responsibility of rulers to create a society in which citizens can enjoy this “good life”. However, Plato said it is only philosophers who truly understand the meaning of ideals such as “good” and “right”, and as such they are the only people capable of leading society.

He therefore advocated a society ruled by a small, elite class of “philosopher kings”. This could be brought about either by putting philosophers into positions of power, or by educating rulers in the discipline of philosophy. Although Plato’s idea seems at odds with both traditional ideas of monarchy and modern notions of democracy, it still has influence today; in many countries there has emerged a class of political leaders who have studied political philosophy before embarking upon their careers.

“Until philosophers are kings… cities will never have rest from their evils.” – Plato, Republic, (c.375 BCE)

Marcus Aurelius – Although he inherited rather than earned the position, Marcus Aurelius (121–180 BCE) became one of the most successful and well liked of the Roman emperors. Apparently confirming Plato’s advocacy of philosophy kings, Aurelius was not only an outstanding political and military leader who maintained peace and prosperity throughout his reign, but also a respected philosopher. His Meditations, written while he was emperor, constitutes a lengthy discourse on self-improvement, personal virtue, and ethics. The work remains an inspiration to philosophers and political leaders today.

The ship of state – In Plato’s Republic, the character Socrates likens society to a ship whose owner (the citizens) has little knowledge of seafaring. To manage the vessel, he relies on a crew of sailors (the politicians), who boast of their seafaring abilities, but nevertheless need the services of a navigator (a philosopher) to determine a safe and efficient course.

The navigator – Representing the philosopher king, the navigator is the only one with the knowledge and understanding of the stars and sea necessary to set the ship’s course.

The crew – Often arguing amongst themselves, the crew (the politicians) can manage the ship, but are lost without the guidance of the navigator.

The ship owner – Standing for the citizens, the ship owner is nominally in charge, but reliant on the navigator and the crew to reach his destination.

g). Moral leadership

Early political philosophers believed that the main role of politics was to create a society of moral citizens. The leader of such a society should therefore be a model of ethical behaviour.

The virtuous ruler – A major purpose of civil society is to protect its citizens and allow them to live safe and happy lives. This is achieved by the rule of law, based on accepted moral principles of what is right and wrong, and good and bad behaviour. In his Republic, Plato argued that society should be overseen by wise philosopher kings who have the necessary knowledge to guide citizens on the true course to a happy existence. Other political philosophers maintained that wisdom in itself is not enough. A good leader should rule in the best interests of the people, and should also be seen to be just and inspire the people’s respect. In short, to establish a virtuous society, a ruler must be seen to be virtuous. Even today, leaders are expected to live according to the moral standards of society, and may lose the respect of the people if they fall short of these.

The “superior person” – Ideas about the importance of morality in the structure of society also developed in ancient China. The philosopher Kong Fuzi (551–479 BCE), known in the West as Confucius, argued that a leader should above all set an example of correct behaviour for the people to follow. He proposed a hierarchal organisation of society, with each member recognising their place and showing respect for those in a higher position and consideration for those below. According to Kong Fuzi, in this way, the correct behaviour of the ruler helps to establish a society of virtuous people, as each citizen aspires to become a morally “superior person”.

Leading by example – Kong Fuzi (Confucius) advocated the concepts of ren and li. Ren is the understanding of how to behave in all situations based on an individual’s place in the hierarchy. Li means ritual and refers to the veneration of ancestors. To help spread the example set by the virtuous ruler, Kong Fuzi also advocated ceremonies that emphasised these moral codes. Here, the ruler’s virtues are likened to the seeds on a grass stalk, which the wind disperses in the field; there they take root and give rise to more stalks and seeds, all similarly virtuous, like the ruler.

[1] The virtues of the ruler – The ruler’s virtues need to be conspicuously displayed at all times, to provide a positive role model for their subjects to follow.

[2] The virtues are dispersed – The virtues displayed by the ruler are emulated by those they come into contact with. They are passed on and spread through the population.

[3] The virtues of the people – The people imitate the leader’s behaviour and cultivate those virtues in themselves. In the process, they provide an example for each other.

Five constant relationships

Kong Fuzi outlined five essential relationship pairings that serve as shorthand for all human relationships.

. Sovereign-subject – Rulers should be benevolent and considerate to subjects, who should be loyal and respectful in return.

. Father-son – Parents should be loving and protective; their children should be obedient and polite in return.

. Husband-wife – Husbands should be good and fair; their wives should be dutiful and understanding in return.

. Elder brother-younger brother – Elder siblings should be gentle and caring; younger siblings should look up to them.

. Friend-friend – Elder friends should be kind and considerate; younger friends should be deferential to their elder friends in return.

h). The art of ruling

While the early political philosophers emphasised the need for wisdom and virtue in a ruler, the Renaissance thinker Niccolò Machiavelli argued that the art of ruling demands more practical qualities.

Political realism – In The Prince (1532), a political treatise in the form of a handbook for rulers, Italian diplomat Machiavelli (1469 –1527) completely shifted the focus of political thinking. Rather than identifying the attributes that a ruler needs in order to foster the people’s moral well-being, or considering how society should be led in an ideal world, Machiavelli put morality aside. Instead, he offered a more realistic description of ruling in the world as it actually is and focused on the practical aspects of governing.

Due to his advocacy of somewhat unscrupulous methods, “Machiavellian” became a byword for political deviousness, but the move from morality to pragmatism in political theory was hugely influential, inspiring the more acceptable notion of realpolitik (practical politics). Machiavelli proposed that the outcome of a ruler’s actions – for the people, the state, and the leader themselves – are of utmost importance. At the core of Machiavelli’s revolutionary approach to the art of ruling was the idea that there is a difference between personal and political morality. The responsibilities of a ruler are different from those of people in everyday life: for the good of the state and its people, it is often necessary for a ruler to act in a way that would be considered unethical in other circumstances. According to Machiavelli, what matters is the outcome – the bigger picture. This necessitates a particular set of political skills, very different from the wisdom and morality advocated previously.

To govern effectively, a ruler has to be prepared to break with conventional morality – using manipulation, bribery, deception, and even violence to retain power and supremacy, and to earn the respect of the people. Asked whether it is better for a ruler to inspire love or fear in their subjects, Machiavelli answered that ideally they should do both, but if there has to be a choice, it is safer to be feared than to be loved.

The end justifies the means – Machiavelli was one of the first philosophers to argue that the morality of an action should be judged by its outcome rather than its principles, especially in matters to do with political leadership. In effect, he said that for a ruler, the end justifies the means.

Decisive Machiavelli advised that a ruler should be either “a true friend or a downright enemy” to gain respect. It is better to be decisive and take one side than be neutral.

Forceful According to Machiavelli, a ruler should have the ferocity of a lion and be prepared to use force and violence when necessary to protect themself and their people.

“It is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity.” – Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince (1532)

Ludwig von Rochau – The term realpolitik was coined by the German writer Ludwig von Rochau (1810–73). Something of a firebrand, he was jailed as a student for his part in an uprising in Frankfurt in 1833. He escaped and lived in exile in France and Italy, working as a travel writer before returning to Germany where he became a political journalist. In 1853, von Rochau wrote his seminal treatise Principles of Realpolitik. He later served as a member of the first Reichstag – German parliament – where he represented the National Liberal Party.

i). Choosing leaders

As well as identifying the character and skills required of a good leader, people also need a method of ensuring that these leaders are chosen to rule.

Passing down power – In early societies, leaders emerged naturally from the people. In many cases, these leaders established a tradition of nominating their successor, typically from the next generation of their own family. As communities evolved into city-states and nations, the practice of handing down the right to rule was often maintained. Monarchs of nations were seen as the heads of ruling families, and their right to rule was accepted. As power was passed down from generation to generation, dynasties became established: children were born to rule, and some rulers even believed themselves to have been divinely appointed. From the 18th century onwards, the majority of monarchies were overthrown and replaced with governments whose right to rule was established by military force or via the choice of the citizens, using a system of voting.

Other than a handful of absolute monarchs, the few remaining kings and queens now have only limited powers, which are granted to them by the elected government in what is known as a constitutional monarchy.

However, in many cases, the notion of a ruling class has not completely disappeared. Aristocrats, generals, and other powerful people often claim entitlement to power, not through birth, but because of educational, financial, or other advantageous influences. Even in democracies, elected leaders are often drawn from a professional political class. In the late 20th century, democracies including the United States and Singapore had father and son leaders.

Born to rule?

Historically, the most common kind of leadership has been a hereditary monarchy, whether the title of the ruler was king, queen, emperor, or sultan. In the modern era, however, the idea of rule as a birthright has largely been replaced by a rule of elected leadership.

Line of succession – A monarch’s position has almost always been hereditary, with power passing from one generation to the next. The line of succession has usually been from father to eldest son.

Hereditary power – In many societies, the monarch was believed to have been chosen by God, with a divine right to rule – what the ancient Chinese called the “mandate of heaven”.

Aristocracy – The relatives of monarchs have often been given titles, and some limited local power. Similar honours have also sometimes been bestowed on people who have been of use to the monarch.

Elected representatives – In a democracy, the president or prime minister and their government are elected not simply to rule but to represent the views and wishes of the people.

Electorate – In democracies, the people have a say in who should be their leader: citizens are entitled to vote in an election to decide who will represent their interests.

“The right of voting… is the primary right by which other rights are protected.” – Thomas Paine, political writer, Dissertation on First Principles of Government (1795)

How To Remove a Leader – In democracies, leaders can be voted out of office by the electorate, but there are other ways to bring about a change of rule.

. Revolution by citizens, often involving violent protest, has been used to world-changing effect, especially against tyrannical leaders.

. Coups are a threat in nations where the government falls out of favour with the leaders of its armed forces.

. Regime change by an external power is uncommon, but it may sometimes happen that one state removes another state’s leader by instigating a revolution, coup, or military invasion.

j). The will of the people

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s notion of government by “the will of the people” has been realised in the many democratic countries that exist today.

A say in government – The idea that citizens should have a say in how their society is governed is an old one, and a form of democracy – or rule by the people – was established in the city-state of Athens in ancient Greece. But traditional ideas about rule by an all-powerful monarch persisted, and it is only since the 18th and 19th centuries that citizens have truly begun to have a political voice.

The extending of power from an elite to the people has been a gradual process. In many early democracies, only a particular class was given the right to vote, for example, property-owning men – women got the vote much later – but today, democracy generally involves the participation of all adult citizens.

Elected officials – With nations numbering often tens of millions of citizens, it is clearly impractical for every single person to participate directly in the decision-making process – proposing, debating, and voting on legislation: a system known as direct democracy. And so, almost invariably, nations have adopted some form of representative democracy. Under this system, citizens vote to elect a person, or persons, to act on their behalf and represent their interests.

In a representative democracy, candidates put themselves forward for election and campaign on a range of issues and policies, often aligning themselves with a political party or a particular ideology. Citizens generally vote for the candidate who best represents their own views. Increasingly, these elected representatives are members of a class of professional politicians.

Types of democracy – The original democracy was a form of direct democracy, in which eligible citizens voted on each issue before a decision was made. However, as the size of the electorates grew and the decisions to be made grew more complex, this proved impracticable, and instead a form of representative democracy evolved.

Direct Democracy vs. Representative Democracy

Direct democracy

[1] The role of the citizens – When a new law is proposed, all eligible citizens are invited to debate the issue and to vote for or against it.

[2] No intermediaries – The citizens vote on specific proposals for laws, rather than voting for a person or a party to make those decisions on their behalf. In this way, citizens have a direct say in legislation.

[3] Choosing new legislation – The votes of the citizens are counted, and the decision of the majority determines which proposals are adopted.

[4] New law selected – The proposal selected directly by the majority of the citizens becomes law.

Representative democracy

[1] The role of the citizens – Citizens are periodically invited to vote in elections for people or parties to represent their interests.

[2] Representatives selected – The number of votes in favour determines which candidates are elected to act on behalf of the citizens.

[3] Representatives vote – When a new law is proposed, the elected representatives debate the issue and vote.

[4] Choosing new legislation – The votes of the elected representatives are counted, and the decision of the majority determines which proposals are adopted.

[5] New law selected – The proposal selected by the majority of the elected representatives becomes law.

“Less than half of the world’s population lives in a fully democratic nation.” – Economist Intelligence Unit (2020)

Ancient Athens – The first ever democracies were established in ancient Greece. Historians believe that several city-states in the region adopted democratic constitutions, but the best known of these is Athens. After the tyrant Hippias was overthrown in 510 BCE, Cleisthenes, his successor as leader of Athens, introduced reforms including a form of direct democracy. This was limited to only a select section of the male citizens, but nevertheless it gave them a say in the government of the city-state. Eligible citizens met on a hill above the city to debate and vote.

2. Political theory

Political ideologies

All political parties, groups, and movements are underpinned by an ideology, or a set of commonly held ideas, beliefs, and principles. These ideas outline how a party believes society should be organised and how power should be distributed within a country or state. A party’s ideology will be reflected in its core social, political, and cultural values and how it views matters such as the role of government, the economy, social welfare, and civil liberties.

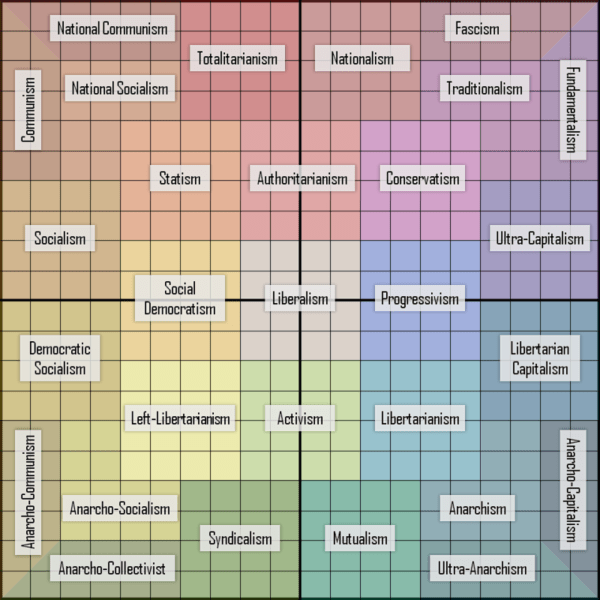

Two axes – A political “spectrum” plots ideologies on a horizontal axis, with communism on the far left and fascism on the far right. However, an ideology can be economically left-wing but socially conservative. A political “compass”, which adds a vertical axis from authoritarian to libertarian, therefore allows a subtler positioning.

. Authoritarian political standpoints favour strict, rigid adherence to one authority at the expense of personal freedom.

. Libertarian political standpoints favour complete freedom of choice and individual rights. Libertarianism lies in absolute opposition to authoritarianism.

. “Left” and “right” originate from the French Revolution (1789–99) when revolutionaries sat to the left of the National Assembly and monarchists sat to the right.

Core values – Political ideologies can be difficult to define precisely. Even those within the same grouping vary. As a general rule, opposing ideologies have opposing views. Both left- and right-wing ideologies have some core values.

Left – Ideologies, such as communism and socialism, favour equal rights, social justice, public ownership, and provision of welfare funded via general taxation.

Right – Ideologies, such as conservatism, adhere to private enterprise, competition, individual freedom, social order, and minimal state interference.

We will look more closely at some of the specific categories of political ideology displayed on the two axes political spectrum graph below.

“… no system, not even the most inhuman, can continue to exist without an ideology.” – Joe Slovo, South African politician

a). Liberalism –Sitting close to the libertarian axis, liberalism is a political ideology which advocates the protection of an individual’s rights and freedoms, but not at a cost to others.

Encompassing a broad range of political and philosophical ideas, liberalism is based on principles of equality and liberty. Humans have basic rights that must be protected, provided they do no harm.

Rights and freedoms

Liberalism is a political movement deeply rooted in ideas of social justice, social reform, and civil and human rights. Socially and politically, supporters of liberalism are committed to freedom of speech, democracy, tolerance, and equality before the law. As a movement, liberalism is reformist rather than revolutionary, and is often regarded as progressive, with a proven record of backing social causes such as the rights of women, disabled people, and LGBTQ+ individuals.

Liberalism emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries as a challenge to the long-held belief in hereditary privilege and the “divine right” of kings. English philosopher John Locke laid its foundations when he argued that humans have natural rights that are universal and inalienable. These principles were later incorporated into the constitutions of the US and France. A later English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), who was the founder of utilitarianism, contributed to liberalism by arguing that decisions should be made on the principle of achieving the greatest happiness for the greatest number. One of the most significant liberal thinkers of the time was John Stuart Mill (1806–73). An English philosopher and economist, he advocated democratically elected governments whose role should be to protect the rights of the individual. Mill believed that government had a social role in health, education, and mitigating poverty. This type of social liberalism was influential, particularly in Britain, where liberal politician William Beveridge (1879–1963) published his 1942 report, laying the basis for the welfare state, which was implemented in 1948.

Economic liberalism

Economically, liberalism favours a capitalist free market, free trade and competition, and the private ownership of industries and property. This approach was developed by Scottish economist Adam Smith (1723–90), whose influential 1776 work The Wealth of Nations argued for a free-market economy that would allow the laws of supply and demand to find their own level. Later liberal economists, notably John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), argued that governments should intervene in times of economic hardship.

Liberalism has influenced government policies in many Western democracies. Recently, some countries have witnessed the rise of neoliberalism, which supports extreme free-market economies, and libertarianism, which argues for unrestrained personal liberties.

Bentham and Mill’s Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is a theory of morality that promotes actions that cause happiness and opposes actions that cause harm. Jeremy Bentham believed that happiness could be measured with a “Hedonic Calculus” (an algorithm for calculating pleasure). He argued that the right course of action is one that leads to the happiness of the greatest number of people: the concept of the “greatest good”. John Stuart Mill supported this principle but was concerned about its political implications. He worried that it could allow a tyrannical majority rule that dismissed the happiness of minority groups. Instead, he advocated laws that gave all people the freedom to pursue happiness.

The harm principle

John Stuart Mill believed that each individual should be free to live life as they please, provided they do no harm to others. This is known as Mill’s “harm principle”. In his essay On Liberty (1859), Mill said that the only justification for an authority to limit an individual’s actions would be to prevent harm to others. On this basis, for instance, a government would be justified in imposing noise restrictions. Local authorities sometimes impose noise regulations and society has a duty to do this where the freedom of others is being harmed or interfered with.

b). Conservatism

Conservatives believe in the importance of traditional social and political structures and strive to preserve them. Their key values are law and order, gradual change, and belief in a governing class.

Gradual change

Modern conservatism emerged in the 18th century, partly as a reaction to the upheavals of the French Revolution, which began in 1789. The following year, Irish statesman Edmund Burke (1729–97) published a highly influential political pamphlet titled Reflections on the Revolution in France. In this, he deplored the rapid destruction of social structures in France and the revolutionaries’ attempts to replace the wisdom accumulated by previous generations with abstract ideas of “liberty, fraternity, and equality”. Burke recognised that social change might be needed, but he rejected revolution. Instead, he argued that change should evolve gradually. Burke’s theories remain central to the political ideology of modern conservatism.

Structured society

For conservatives, society is naturally hierarchical, and the rule of law is vital to ensure order and stability. Governments tend to be interventionist, looking after the good of the nation. Conservatives support the idea of a ruling elite, made up of the most experienced and best equipped to lead. Once this would have been a privileged hereditary class; today it is more likely to comprise well-educated professionals and financiers. Conservatism favours capitalism, and promotes private industry, enterprise, free trade, and the creation of wealth, which it believes will “trickle down” to the less well off. Conservative governments play a limited role in trade, industry, and, increasingly, in welfare provision. Socially and culturally, conservatism promotes the value of traditional institutions and processes.

Worldwide conservatism

In practice, conservatism can vary from liberal to more authoritarian forms. Most modern Western European conservative parties tend to be economically conservative but may be socially liberal, recognising, for example, same-sex civil partnerships. In the US, however, modern conservatism is closely linked to the right-wing Republican Party, which believes in small government and traditional values. In India, the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) represents conservative politics, promoting a cultural nationalism and a conservative social and economic policy. In the 21st century, Russia has also pursued conservative policies in social, cultural, and political matters.

Conservative values

Underpinning conservatism is a belief in a hierarchical social order rather than equality. In such a society, the rule of law is vital to preserve order and prevent anarchy. Conservatives belief in maintaining traditional values that have evolved over time. If change is necessary, it should be implemented gradually.

Religion – Organised religion is highly regarded by conservatives for its traditional values, which reinforces stability and order and provide a moral compass.

Traditional family structure – Conservatives value traditional family structures. They are seen as stable, and sharing common values that contribute to social order.

Private property – A core conservative belief is the right to own property. Conservatism supports laws that protect inherited wealth and properties.

Hierarchical society – Most conservatives would not support hereditary power, but do believe in an elite class that is best qualified to rule.

Paternalistic government – Paternalistic conservatism emphasises state intervention to cultivate a good life for all of its citizens.

Work ethic – Conservatives believe in success through hard work and personal responsibility, rather than reliance on the state.

Patriotism – Not all conservatives are nationalistic; however, conservatism encourages a love of country and the idea of shared national values.

“I am a Conservative to preserve all that is good in our constitution… I seek to preserve property and to respect order…” – Benjamin Disraeli, former British prime minister, taken from a speech at High Wycombe, UK (1832)

c). Neoliberalism

The ideology of neoliberalism stands for meritocracy, minimal government, low taxation, privatisation, deregulation, and free-market economics.

Free markets

The roots of neoliberalism lie in the ideas of the 18th-century philosopher Adam Smith, who argued that free markets are the best means of ensuring wealth is distributed fairly in society. However, neoliberalism is a 20th-century philosophy that was developed in opposition to the policies of state intervention pursued in Europe and the US during the Great Depression and the period that followed World War II. One of the first proponents of neoliberalism was Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992), who argued that free markets respond directly to individual needs, and so deliver benefits to society much more efficiently than the state. Another neoliberal thinker was US economist Milton Friedman (1912–2006), who argued that a key role of government is to control the money supply.

The neoliberal world

Neoliberals claim that individuals should be responsible for themselves, and that the role of government is to oversee economic growth, rather than spend money on public services. In the 1980s, British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and US president Ronald Reagan put this philosophy into practice, fomenting a period of social unrest. They privatised public services, deregulated businesses and banks, reduced taxes, and also cut government spending on essential social services. Neoliberalism has since been adopted by many countries around the world, and now influences the policies of global institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. However, its critics argue that although it has made bankers, financiers, and global corporations extremely rich, it has also resulted in widespread income inequality.

Rolling back the state

Neoliberals argue that the state should play only a minimal role in managing a nation’s affairs. This is in sharp contrast to the post-World War II view that the state should pay for a range of public services, including education, transport, and healthcare. They also claim that economies stagnate when governments spend too much money on public utilities and services, which instead should be run as businesses by private companies.

The privatisation of public services – According to neoliberalist theory, social services, such as healthcare and education, and public utilities, such as transport, prisons, and postal services, should be privatised in order to save public money and increase economic efficiency.

The minimal state – In neoliberalist systems, individuals should be free to pursue their own goals, and so should be free from state interference. The state’s role should therefore be limited to ensuring that the market is operating freely.

The deregulation of business – Neoliberals argue that all restrictions on trade and business should be removed. This will allow the economy to grow and create more jobs, which in turn will enable more people to spend money and further stimulate the economy.

The poverty gap – According to neoliberal theory, anyone can achieve their goals and be wealthy by working hard. In practice, however, neoliberalism has actually increased income inequality: that is, the rich have got richer, and the poor have got poorer.

Terms to understand

. Deregulation is the reduction of governmental control, such as removing laws, often in particular industries.

. Privatisation is the transfer of a business or service from public to private ownership and control.

. Meritocracies are political systems in which people are awarded success or power on the basis of ability.

. Free markets are economic systems based on supply and demand with little or no government intervention.

d). Libertarianism

Individualism and freedom of choice lie at the heart of libertarianism, a political philosophy that unites both the extreme left and the extreme right in opposing state interference.

Individual liberty

Libertarianism has its origins in the ideas of classical liberal thinkers such as John Locke and John Stuart Mill (see above). However, it also has left- and right-wing traditions, which have appeared more recently.

The left-wing tradition has its roots in the writings of the 19th-century anarchists and libertarian socialists. One of the earliest uses of the term “libertarian” was in 1895, when French anarchist Sébastien Faure (1858–1942) started publishing his journal Le Libertaire (The Libertarian). A more recent left-wing libertarian was the American environmentalist Murray Bookchin (1921–2006). His ideas shaped both the anti-globalisation movement and the Occupy movement, which began in the US in October 2011 before spreading worldwide. Coining the slogan “We are the 99%”, the Occupy movement attacked crony corporatism and corrupt financiers, and highlighted the glaring inequalities between the very rich (the 1 per cent) and the rest of society (the 99 per cent).

Right-wing libertarianism

In recent years, a right-wing version of libertarianism has also become influential, particularly in the US. Right-wing libertarians are anti-egalitarian and support capitalism, free-market enterprise, and the rights of private ownership. Influenced by the American philosopher Robert Nozick (1938–2002), many right-wing libertarians argue that taxation is theft, and that whatever a person produces, owns, or inherits should be theirs and theirs alone. An example of right-wing libertarianism was the Tea Party movement, which appeared in the US in 2009. Conservative voters congregated at mass gatherings known as “tea parties”, at which they demanded that President Obama’s healthcare law be scrapped, and the national debt reduced by cutting back on social spending.

“Libertarians are self-governors in both personal and economic matters.” – Advocates for Self-Government, libertarian organisation (1995)

Case study – The Free State Project

In 2001, Jason Sorens, then a student at Yale University, founded a libertarian movement known as the Free State Project. He encouraged American libertarians to move to the state of New Hampshire, believing that 20,000 “movers” would be sufficient to begin the process of changing the political culture of the state. The ultimate goal of the project is for libertarians to take over the New Hampshire government, and to start running it according to libertarian principles. To date, over 5,000 libertarians have migrated to the state.

Individualism and liberty

Libertarians share a mistrust of government, but many disagree on the question of how individual liberties should be protected. Left-wing libertarians claim that capitalism creates inherently unequal societies, whereas right-wing libertarians argue that only capitalism frees people to live in the way they wish.

Capitalism – Left-wing libertarians want to be free of capitalism, which they argue infringes personal liberty by generating inequality.

The state – Both left- and right-wing libertarians believe that the state should only serve to protect individuals from harm.

Taxation – Right-wing libertarians want to be free of taxation, which they argue is a form of theft practised by the state.

e). Anarchism

The origins of the word anarchism lie in the ancient Greek term anarkhia, meaning “without rulers”. In practice, it means the rejection of political authority. Anarchists believe the people themselves should make the rules.

Rule from the bottom up

Anarchists value personal liberty above all and stand against any form of authority that threatens an individual’s freedom. They view the state as oppressive and believe it rules by coercion. To them, even democratically elected rulers are illegitimate. Anarchists favour the abolition of the state, leaving people free to organise themselves in self-governing groups, free from any form of political, economic, or social hierarchies. Anarchism is often associated with the far left axis of the political spectrum, but it can also appeal to those on the right. Anarcho-capitalism combines libertarian (see above) elements of anarchism with support for free-market capitalism.

Theory and practice

Anarchism is built on the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau (see above), who believe that people are good and that the state deprives them of their natural freedoms. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–65), French philosopher and first self-declared anarchist, said that “property is theft”. Russian revolutionary Peter Kropotkin (1842–1921) fused communism and anarchism to form anarcho-communism. He argued for the abolition of private property in favour of common ownership, and for replacing the state with direct democracy. There are small-scale examples where anarchism has been put into practice. In Spain before the Civil War (1936–39), anarchists set up self-governing communities, but the experiment was cut short when the country fell to fascist rule. The communal-living kibbutz movement in Israel was inspired by anarchist ideas of self-management, and Christiana, a commune of close to 1,000 people in Copenhagen, has operated outside of Danish authority since 1971.

Anarchist principles can also be seen in modern anti-globalisation and environmental movements, such as the direct-action group Extinction Rebellion.

Forms of anarchism

Anarchist ideas vary broadly between being focused on individuals or co-operative groups, and between left versus right. On the left, mutualism and anarcho-syndicalism would replace the state with increasingly left-wing policies. On the right, anarcho-capitalists oppose the state but not free markets, property, or the rule of law.

Ending the state

At the heart of anarchism is the abolition of the state. Anarchists believe the state is inherently corrupt because it will always act in the interest of a ruling elite.

“Anarchism means voluntary co-operation instead of forced participation.” – Alexander Berkman, American anarchist, ABC of Anarchism (1929)

Individual anarchism – A person believes in retreating from civil society and living according to their own conscience, unconstrained by the authority of others.

Social anarchism – People voluntarily join together to self-govern on a voluntary, co-operative basis with no hierarchies and no government dictating the rules.

Mutualism – Providing a link between individual and social anarchism, mutualism emphasises social equality, trade unions, and mutual (members-owned) banks with zero-interest loans.

Anarcho-syndicalism – This early 20th-century movement aimed to overthrow capitalism and organise the co-operative management of production based on workers’ rights and power.

Anarchism vs. Anarchy

Anarchism is often confused with anarchy. Anarchy is the complete absence of rule, which has become synonymous with chaos, violent disorder, and lawlessness. The utopian ideal of anarchism would be an ordered society based on self-discipline, self-reflection, and self-imposed rules. However, in practice, the implementation of anarchism could risk a power vacuum and lead to anarchy.

f). Fascism

Sitting on the far right of the political spectrum, fascism is an extreme nationalist authoritarian ideology that prioritises the power and unity of the state over the freedoms of individuals.

Restoring glory

Fascism dates back to the rise of nationalism in the late 19th century. The ideology gained momentum after World War I (1914–18), fuelled by the political chaos that followed the conflict. Italy was the first country to become a fascist state. In 1919, Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) formed the Italian Fascist Party. Declaring that he would receive the glory of the Roman Empire, he seized power in 1922, later ruling as a dictator. Working closely with Italian businesses, Mussolini set out to restructure Italy’s economy and expand its influence.

Fascism spread throughout Europe in the years that followed. In 1939, after a civil war, nationalist General Francisco Franco (1892–1975) seized power in Spain and ruled it as a fascist state, quashing all opposition. In neighbouring Portugal, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970) ruled as a dictator from 1932 to 1968, his policies incorporating many fascist principles.

Fascism took a different form in Germany. Known as National Socialism or Nazism, it was advocated by Adolf Hitler, who gained support by exploiting the humiliation Germany felt after World War I. Nazism was deeply racist and antisemitic. Promoting the concept of a “pure” Aryan race, the Nazis committed genocide against the Jews and slaughtered many minor groups.

State control

“All within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state.” – Benito Mussolini, Italian dictator (c.1920s)

Fascism is nationalistic: the strength of the nation state takes precedence over the rights and freedoms of the individual. In Italy, the state restricted the press, only allowing media that expressed a “faithfulness to the Fatherland”.

Regimented society

Strength in unity is a core fascist principle. A fascist state is rigidly structured and hierarchical. The state controls all activity, including the economy.

Supremacy of the nation state

Within a fascist society the state or nation is supreme. Nationalism and state control are fundamental.

Strong leader – A feature of fascism has been leadership by a strong, charismatic man who is presented as the only person capable of restoring the nation.

Rhetoric – Pageantry, spectacular rallies, and stirring speeches are used to impress citizens.

Symbolism – Some fascist symbols are ancient, such as the fasces, or bundle of rods, adopted by the Italian Fascist Party.

Militia – Masculinity and militarism are common themes within fascism. Fascist leaders utilise uniformed militia to create fear and impose military rule.

Suppression – Fascism is anti-liberal and anti-egalitarian. It makes considerable use of force to quash opposition; censorship is common, and free speech is forbidden.

Neo-Fascism

Today, no regime refers to itself as fascist. However, the term neo-fascist is often used to describe political parties or movements – such as the National Rally in France or Golden Dawn in Greece – whose ideologies resemble those of 20th-century fascist movements. In the US, white supremacist groups are countered by the “antifa”, or anti-fascist, movement.

g). Nationalism

The goal of nationalism is to unite the people of a country under a single national identity in order to encourage support for the country and to promote its interests.

Shared identity

Nationalism is an ideology based on the idea that the nation and the state are one, and that a nation should not only be self-governing but also free from the influence of other nations. It differs from patriotism, which is a love of one’s country, regardless of the language, culture, or ethnic identity of its people.

Nationalists argue that the people of a country should celebrate their common identity as members of that country, and so stand united against their enemies. However, in doing so, they may also encourage citizens to feel a sense of superiority over other nations and peoples. Since the late 18th century, nationalism has been a powerful driving force for change. It swept away France’s monarchy during the French Revolution, which began in 1789, and became the rallying cry of the Risorgimento, the movement that unified the Italian states into a single state in 1861. Likewise, it underpinned the unification of Germany in 1871, when several German princedoms formed a nation state.

Nationalism has also inspired numerous liberation movements that have fought to free countries from imperial control. In India, for example, it drove an independence movement that ended British colonial rule over the country in 1947. In Africa, similar movements inspired many states to claim independence from other colonial powers, such as France and Germany.

However, there is a darker form of nationalism, which encourages racism against minority ethnic groups within a nation, and xenophobia against people from other countries, such as refugees and asylum seekers.

“Nationalism is power hunger tempered by self-deception.” – George Orwell, British writer, Notes on Nationalism (1945)

Rise of extremism

Extreme nationalism appears to be on the rise in the 21st century, with the emergence of far-right white supremacy movements in the US, and Hindu nationalism in India. Such movements threaten to undermine the liberal ideals of nationalism.

What is a nation?

A nation is a community of people who live within a defined geographical area. Typically, the community shares a common language, culture, and ethnic heritage, but it may also be home to people from other cultures who share the nation’s values. In liberal countries, the national identity transcends the ethnic differences of citizens. In less liberal countries, ethnicity may be a defining feature of the nation.

Liberal nationalism vs. Ethno-nationalism

. Liberal nationalists celebrate the sense of shared identity that people feel on belonging to the same nation, regardless of their ethnicity.

Soft borders – Interaction between nations is encouraged, and borders between them are either open or regulated.

Deportation – Depending on government attitudes, people perceived as not sharing a nation’s values may be deported or refused entry.

. Ethno-nationalists define nationalism in terms of the “dominant” ethnicity. They often see other ethnicities as inferior.

Hard borders – Interaction between nations is minimised, and borders between them are often militarised.

Reinforcement – The identity of citizens is constantly reinforced by the nation’s culture.

Marginalisation – People who do not embrace the nation’s culture can be seen as sympathisers for other cultures, and so are often marginalised or treated as enemies.

Case study – Kurdish nationalism

Many states contain regions that are populated by peoples who have their own ethnic and cultural identities, and so wish to build their own states. One such people are the Kurds, between 25 and 35 million of whom live in the mountains bordering Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Armenia. The Kurds have been fighting to gain independence from these countries since 1920 but remain the largest stateless ethnic group in the world.

h). Populism

Populism effectively pits ordinary people against existing politicians, governments, or institutions, which are portrayed as elitist and corrupt. A charismatic leader typically presents themselves as the people’s champion.

A divisive ideology

Some political scientists describe populism as a “thin ideology”, because it rarely has or advocates an economic or social programme. Instead, it depends on being provocative and divisive. Populism is underpinned by the idea that society is split into two, often antagonistic, camps: “the people” and “the elite”.

Populism has manifested in both left- and right-wing politics. Examples of left-wing populism include the Occupy movement, which highlighted economic and social hardship, coining the slogan “We are the 99%”, the Podemos party in Spain, which challenged the country’s austerity measures, and former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. On the right, examples include former US president Donald Trump, Hungary’s prime minister Victor Orbán, and Nigel Farage, former leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), who claimed that the European Union (EU) was undemocratic and a threat to British sovereignty. Farage now leads the far-right Reform UK political party in the UK following Brexit.

Populist themes

Lack of democracy is a common theme in populist discourse, and is frequently used to attack perceived elites. Populist politicians are elected through the democratic process but may subsequently show little respect for democracy, as demonstrated when Trump refused to accept the result of the 2020 US presidential election.

Populist politicians gain support by tapping into people’s feelings of exclusion. A populist leader, who may not be a conventional politician, rallies support by stirring up prejudice and blaming others for social injustice. This may be directed at the sitting government, intellectuals, or the media, any of whom are presented as overriding people’s rights and freedoms. Populism, particularly on the right, can be aligned with nationalism, enabling blame to be directed towards immigrants or minority ethnic groups within a country.

Populism in the 21st century

In recent years, populist politicians have gained support in many countries. They have done so in response to various crises that have shaken the world, such as the financial crisis of 2007–08 and the displacement of millions of people due to wars in the Middle East. At such times, people are prone to seek easy answers to complicated problems, and so are more easily swayed by politicians who prey on their anxieties about immigration and unemployment. Such crises also increase people’s disillusionment with traditional politicians and political processes.

The people vs. the elite

According to populism, society is divided into two opposing groups: the “people” and the “elite”. The people are considered to be pure, exemplary citizens, while the elites are portrayed as undemocratic, corrupt, and uninterested in the needs of the people.

The people – The people are presented as morally superior. However, rather than reflecting the whole of society, they are often from a particular social class or religious group.

The charismatic leader – Claiming to represent the will of the people, populist leaders are skilled at whipping up a crowd. They are not necessarily aligned with a political party and are sometimes described as “demagogues”.

The elite – Members of the elite are presented as corrupt and self-interested. They may be bankers, scientists, the media, intellectuals, or a sitting government.

i). Socialism

Socialism is range of political and economic theories that aim to end the exploitation of workers, ensuring that each person can enjoy the wealth created by their labour but only receive a share equal to their contribution.

Social justice

Socialism developed in the early 19th century in response to the growth of capitalism during the Industrial Revolution. German philosopher Karl Marx (1818–83) defined its principles, claiming that socialism was the first step towards communism. Socialists argue that the means of production must be regulated to protect workers from exploitation. Some socialists believe this is only possible if the means of production is transferred from private hands to public or state ownership. In a socialist country, each individual receives profits that reflect the size of their contribution. The state, as opposed to private enterprise, is often responsible for funding social necessities, such as the provision of healthcare, education, housing, and energy, through a tax system.

Socialism has been profoundly influential, but its tenets have been open to interpretation. Revolutionary socialists argue for a seizure of power by the working class. Others believe that socialist policies can be achieved via elected governments that best reflect workers’ interests.

“Socialism is their name for almost anything that helps all the people.” – Harry S. Truman, former US president, New York speech (1952)

Terms to understand

. Means of production are the raw materials, tools, factories, and infrastructure needed to produce goods.

. Capitalism is a political system in which a country’s trade and industry are controlled by private owners, rather than the state.

Challenging capitalism

Socialism sits on the left of the political spectrum. Fundamentally, it challenges the capitalist system, advocating public ownership and co-operation over competition, private ownership, and private profits. Socialists strive for collective responsibility rather than the liberal emphasis on individual rights and freedoms.

Common ownership – The means of production – including tools, machinery, and factories – are collectively owned in many socialist societies, either by the state or by the workers in the form of co-operatives.

Society is co-operative – Individuals work together and make decisions democratically. In the early and mid-1800s, “utopian” socialists experimented with self-sufficient communities.

Their abilities – Each worker contributes to production and to the wealth of the state, according to their abilities and skills.

Distribution – The state compensates individuals according to their contribution. Socialists have historically supported communal ownership of resources and central planning to achieve an equitable distribution.

j). Communism

Communism is a political, social, and economic ideology that promotes the idea of a classless society, one in which private ownership does not exist and the state has withered away.

The Communist Manifesto

First described by the German philosopher Karl Marx (1818–83) and Friedrich Engels (1820–95) in The Communist Manifesto (1848), communism shares its anti-capitalist roots with socialism. However, Marx considered socialism to be only an intermediate stage on the path to communism.

Unlike socialists, communists envisage a society without social class, in which each person works for the good of everyone else, and all private property has been abolished. In a perfect communist system, the state’s political and social institutions are rendered obsolete as society becomes capable of governing itself, without the coercive enforcement of the law. Engels described this process as the state “withering away”. Marx believed that the only way to bring about communism was through revolution, and that the workers of all countries had to unite and free themselves from capitalist oppression to create a world run by and for the working class.

Communism and revolution

Marx was writing during revolutionary times – there was a wave of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848 – but his political ideas only started to impact society in the 20th century.

In 1917, Russian Marxist Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov (1870–1924), better known as Lenin, led Russian industrial workers into a revolution to overthrow the tsar (supreme ruler), establishing the world’s first socialist state. Unlike Marx, Lenin believed in the importance of a “vanguard of revolutionaries” – a party of working-class socialists known as the Bolsheviks (from the Russian bolshinstvo, meaning “majority”) who would mobilise the proletariat into bringing down the ruling classes.

However, after the revolution, rather than introducing common ownership and creating a truly communist nation, the Bolsheviks took ownership of the machinery of state. From 1924, under Lenin’s successor, Joseph Stalin (1878–1953), the Soviet Union became a one-party dictatorship until its collapse in 1991.

In 1949, Mao Zedong (1893– 1976) led a communist revolution in China. Other countries also adopted communist systems, and by 1980 around 1.5 billion people out of a global population of 4.4 billion were living in a country ruled by a communist political party.

Class struggle

For Marx, all history was the history of struggle and conflict between social classes. He adapted the ideas of German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770–1831), who stated that the only way to understand things is to see them as part of a march of historical progress that will ultimately lead to human freedom. For Marx, this state of “human freedom” was communism.

[1] Nobles and Slaves – In the ancient and classical worlds, members of the ruling class were of noble birth. They owned the land and its workers, and controlled laws.

Workers in the ancient and classical worlds were often enslaved people. Their lives, bodies, labour, and the goods they produced were owned by the nobility.

[2] Lords and Serfs – Under the feudal system of medieval Europe, agricultural land was the main source of wealth. It was owned by lords, who inherited or were given the land by the monarch.

A class of workers, or serfs, farmed the land. They were not slaves but had to work for the lords in exchange for a small amount of the produce they created.

[3] Bourgeoisie and Proletariat – Capitalism created a new owing class that Marx called the bourgeoisie. They owned the means of production and took all the profits.

The new working class, or proletariat, laboured in the mills and factories owned by the bourgeoisie in poor conditions for minimal wages.

[4] Socialism – Marx believed that tensions between the bourgeoisie and proletariat would cause the proletariat to rise up, seize the means of production, and create a socialist society.

[5] Communism – Eventually, socialism would be so successful that classes would disappear altogether, the state would wither away, and communism would be achieved.

“What the bourgeoisie… produces . . . are its own grave-diggers.” – Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto (1848)

k). Social democracy

Social democracy is a socialist ideology that is based on the belief that capitalism can be reformed, or humanised, to ensure comprehensive welfare provision for everybody.

Socialism and capitalism meet

The roots of social democracy lie in the ideas of German political theorist Eduard Bernstein (1850–1932), an associate of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He suggested a new political system based on his interpretation of Marxism. His idea for social democracy incorporates similar values to socialism in that it aims to provide welfare for the disadvantaged, end inequality, and ultimately eradicate poverty. However, unlike socialism, social democracy does not seek to overthrow capitalism but rather to reform it and eliminate its worst injustices.

Social democracy favours a mixed economy that includes state-owned enterprises, particularly those providing public goods and services, such as health, education, and housing, alongside privately or part state-owned businesses. Shareholders and workers manage these private businesses, which are closely regulated by the government. Social democracy sees taxation as a means of wealth distribution, the money raised being used to fund welfare and public services. Social democratic parties of various kinds have been formed in most European countries. In the 1990s, social democratic ideas underpinned a political movement known as the “Third Way”, which aimed to fuse liberal economics with social democratic welfare policies. It was a strand of politics favoured by US president Bill Clinton, in office from 1993 to 2001.

Today social democracy is most often associated with the Nordic countries, where implementation of the “Nordic model” has resulted in high standards of living for the majority of citizens.

The Nordic model

The Nordic model describes the particular social democratic approach of the Nordic countries Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden to economic, social, and cultural policies. The model combines free-market capitalism with extensive social welfare provision, funded by high taxation rates.

Innovation – The Nordic model encourages innovation as a driver for economic growth. There is extensive investment into research and development, particularly in green technologies.