INTRODUCTION

IF A MAN IN A GORILLA SUIT walked across your field of vision, would you notice him? Incredible though it may sound, there is roughly a fifty per cent chance that you would not notice the gorilla if you happened to be concentrating on something else. Known as the “invisible gorilla” phenomenon, or inattentional blindness, this is just one of the amazing and intriguing nuggets mined from the treasure trove of psychology, and which you will find explained on this page.

Did you know, for instance, that Freud was addicted to cocaine, confessed to never having understood women, and believed that when you dream you are flying, your airborne body is a phallic symbol: a giant, flying erection? Did you know that newborn babies may be able to “see” with their tongues; that German stomach ulcers are nearly ten times more responsive to the placebo effect than Brazilian ones; or that, while psychologically healthy people cannot tickle themselves, schizophrenics with delusions of being controlled can tickle themselves?

The narrative here will explain all these bizarre insights, exploring the most interesting and important concepts in psychology. It covers every aspect of this science, from psychoanalysis to behaviourism, counselling to neuroanatomy, personality to the paranormal. Difficult concepts are broken down and explained, illustrated with examples and analysed for their wider significance.

The page also explores the most important contributions of the most important contributors in the history of psychology, from Freud and Jung to Maslow and Reich, Laing and Pavlov to Adler and Zimbardo. Yet the discussion is alert to intriguing trivia. Did you know, for instance, that in the course of his research into conditioning in dogs, Pavlov succeeded in making a dog neurotic? You will learn about the Hawthorne effect, which is where people alter their behaviour when someone is watching, such as when male subjects tolerate higher levels of pain when being watched by an experimenter; and about the Baskerville effect, where superstitious beliefs can cause death. You will learn the truth about Project Pigeon, the outrageous but successful scheme to put pigeons inside missiles to guide them to their targets, and discover the farcical horrors of aversion therapy, including the true story of when psychiatrists in the 1960s claimed to have used 4,000 electrical shocks to turn a homosexual into a bisexual.

Every effort will be made to define and explain technical terms as they arise, but an important distinction that is often poorly understood is worth acknowledging: the difference between the multiple terms derived from the root “psych-”. What is the difference between psychiatry, psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and psychology? Psychology is the study of the psyche, the Greek word for “mind”; this term encompasses all the different strands of philosophical and scientific enquiry into matters concerning the mind. Psychotherapy is the treatment of psychological problems and illness through methods involving psychology, and includes psychoanalysis and aspects of psychiatry. Psychiatry is the branch of medicine devoted to mental illness; it is practised by medical doctors. Psychoanalysis is both a theory of mental structure and function, and a method of psychotherapy. Traditionally, most psychoanalysts were expected to have been trained as psychiatrists, and the terms were often conflated.

Adler and the inferiority complex

ALFRED ADLER (1870–1937) was a doctor with an interest in psychology and education, who was invited by Freud to join the Vienna circle of psychoanalysts and for a time was designated as the heir apparent for psychoanalysis. However, Adler’s theories rapidly evolved away from Freud’s insistence on sex as the psyche’s dominant drive, and the concomitant model of human psychology as primarily a product of past experiences, mainly those of early infancy. Adler believed that power was the true engine of the human psyche, particularly the power of relations between people. For instance, he argued that sibling birth order is an important factor governing personality, a theory rapidly appropriated by folk psychology. The same fate befell many of Adler’s concepts, none more so than the inferiority complex.

Everyone inevitably experiences some feelings of inferiority; Adler’s insight was that such feelings could be the primary driver behind much of human psychology and behaviour, especially in the formative childhood years, as the psyche attempts to compensate for, adapt to, or overcome the feelings. A child who feels physically inferior, for instance, might pursue sports to overcome his feelings, or might turn away from physical activities altogether and become bookish. Adler cited the classical tale of Demosthenes, the great Athenian orator who overcame a childhood speech impediment by training himself to speak with stones in his mouth.

If the emotions and thoughts arising from normal inferiority feelings are suppressed and driven into the unconscious mind, the result may be an inferiority complex. A complex, in psychoanalytic terms, is a system of unconscious desires, thoughts and feelings that acts on the conscious mind, often in an unhealthy or unhelpful fashion. Adler was careful to draw a distinction between normal inferiority feelings and the maladaptive inferiority complex, but this distinction has been lost in the popular appropriation.

Freud took a dim view of Adler’s focus on the psychology of power and inferiority, dismissing his developmental model as an “infantile scuffle”, amounting to little more than vulgar clichés such as “wanting to be on top” and “covering one’s rear”. The relationship between the two men played out Adler’s own theory, with Adler lamenting that he was always “forced to work in [Freud’s] shadow”. Their split turned into a vicious feud, and in 1911 Adler set up his own school of psychoanalysis, which came to be known as Individual Psychology. For a time, he became a world-famous intellectual figure and bestselling author, but his time as the “rock star” of psychoanalysis passed and he died a lonely death in Aberdeen while on a lecture tour. Although his name is little known today, his legacy is widespread in modern psychotherapy and his theories and terms have infiltrated many aspects of popular psychology.

Archetypes and the collective unconscious

In Jungian psychoanalysis, archetypes are embodiments of beliefs/concepts/experiences, which are common to all human psyches and may even be aspects of the underlying nature of reality. Although each individual experiences/encounters an archetype in different forms, the basic seed/scaffold of the archetype is located in the unconscious. Jung believed that since these archetypes are common to the unconscious of all humans they constitute a sort of collective inheritance, which he termed the collective unconscious.

THE CONCEPT OF THE ARCHETYPE grew out of the research and personal life experiences of Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961), a Swiss psychoanalyst who was the anointed heir to Freud’s kingdom before their relationship descended into feuding and bitterness, as with so many of Freud’s associates. An important bone of contention between the two was Jung’s interest in mystical aspects of the psyche, and it is easy to dismiss, as Freud did, archetypes and the collective unconscious as anti-scientific mumbo-jumbo and mere mysticism. But Jung’s conception and discussion of archetypes leaves much room for debate. Did he conceive of the collective unconscious as some sort of world mind or psychic astral plane, or is it simply shorthand for hard-wired, innate aspects of human neurology, which evolved early in our evolutionary history and are therefore encoded in our genes?

Jung certainly compared archetypes to instincts. Like instincts, he believed, archetypes are inherited and hard-wired, but where instincts govern behaviour, archetypes govern thoughts, feelings, and perceptions: specifically what Jungians describe as “psychic apprehensions”. Cognitive psychology, the school of psychology that deals with the mind in terms analogous to computer science, postulates mental modules and programmes that filter and process perceptions, experiences and thoughts, and archetypes can be seen in this light. To put it another way, archetypes are like centres of gravity in the psychic universe, attracting and animating related concepts and imagery.

Jung became “aware” of archetypes partly through his practice, partly through his reading in world literature and cultures, and partly through his own psychic journey. As an analyst he was forcibly struck by the way in which patients he considered relatively simple and uneducated related imagery replete with symbolism from arcane and cross-cultural sources. If they could not have encountered such symbols in their own lives, where could they be coming from? His own experience supplied a telling example: only after a series of dreams in which he saw a four-fold radiating pattern did he discover that this symbol had a name – the mandala – and was a common theme in Eastern cultures. If such concepts had not arisen from personal experience, Jung reasoned, they must be innate, reflecting “psychic apprehensions” that lay at the root of humanity itself, springing from a shared or collective unconscious.

Jung identified a handful of major archetypes (although he allowed that the total number might be unlimited), including the wise old man and his female counterpart, the magna mater, or great mother. Discussing the wise old man, for instance, Jung wrote: “The wise old man appears in dreams in the guise of a magician, priest, teacher, professor, grandfather, or any person possessing authority.” Also, there were the self and the shadow, and the anima and animus (the opposing gender aspects of each individual). These and other archetypes can be spotted everywhere from popular culture (for example, Bugs Bunny as the trickster or Gandalf as the wise old man) to the esoteric (Tarot’s Major Arcana cards influenced Jung’s thinking, as did the symbolism of alchemy and magic).

Aversion therapy

A form of psychotherapy where someone is conditioned to associate specific thoughts and/or behaviours with negative consequences, supposedly with the result that the subject becomes “averse” (i.e. avoids/dislikes) the target thoughts/behaviours. A typical example of aversion therapy is conditioning someone to avoid alcohol by giving them a drug that makes them sick whenever they drink alcohol.

AVERSION THERAPY is a form of behavioural modification or behaviour therapy, which works because animals (including humans) have evolved to learn quickly to avoid dangerous stimuli. Conditioned food aversion is where an association between ingesting something and being sick rapidly leads to a long-lasting and deep-seated aversion (as in the case of someone who gets sick from bad shellfish, and subsequently feels nauseous at the sight, smell, or even thought of shellfish).

As a therapy it developed from work on conditioning, such as Pavlov’s dogs and the Skinner box. For instance, dogs that were trained to associate certain stimuli with electric shocks quickly grew to dislike said stimuli. If such experiments sound cruel, imagine the ethical issues surrounding aversion therapy in humans. Yet such considerations have not stopped aversion therapy from being used from the 1920s to the present day.

SHOCKTAILS

Possibly the first application of aversion therapy was in the treatment of alcohol abuse in 1925, using electric shocks. Ten years later chemical aversion therapy for alcoholism was first tried, and today it is still in use with the drug Antabuse (the proprietary name for disulfuram) prescribed to cause nausea, vomiting, and palpitations when alcohol is consumed.

More controversially, aversion therapy was widely used to “treat” homosexuality, seen as pathological until the late 1960s and beyond. In 1935, for instance, a man was asked to engage in homoerotic fantasies and given electric shocks. A similar experiment from 1963 involved a barefoot man standing on an electrified metal floor and given shocks while being shown pictures of naked men. After 4,000 shocks the subject reportedly became bisexual.

Aversion therapy for homosexuality lurched further into farce in the late 1950s with the development by psychiatrist Kurt Freund of chemical methods. Freund administered apomorphine to cause dangerous and distressing symptoms including nausea and vomiting while showing his victims pictures of naked men. He also developed a device where a band clamped around the penis recorded any engorgement, which was supposed to function as a sort of sexual “lie detector” to ferret out irrepressible erotic responses. Perhaps inevitably, farce eventually led to tragedy in 1964 when a British man with a heart condition died as the result of chemical aversion therapy for homosexuality, after having been administered vomit-inducing drugs in conjunction with a discussion about homosexuality, followed by a dose of LSD while talking about heterosexual fantasies.

As linguist Hugh Rawson points out, “From the standpoint of a person who is forced to undergo it, ‘aversion therapy’ is difficult to distinguish from punishment or torture.” Yet despite this, it was still relatively common in parts of the US as late as the mid-1980s, and is probably still practised around the world.

Barnum effect

The tendency to accept generic statements as accurate personal descriptions, particularly when they are flattering.

ALSO KNOWN AS THE FALLACY of personal validation, the Barnum effect or phenomenon is named for the nineteenth-century US showman and charlatan P.T. Barnum (1810–91), for it incorporates two of his famous dictums: “My secret of success is always to have a little something for everyone” and “There’s a sucker born every minute”. A typical Barnum-effect statement may be detailed or appear specific, but in fact will be vague, ambitious, and/or self-contradictory and thus applicable to everyone. Whether they are aware of it or not, the phenomenon is a major tool of astrologers, psychics and fortune tellers, alongside cold reading and other tricks.

The effect was first demonstrated in 1949 in an experiment by US psychologist Bertram Forer (1914–2000), who gave college students personality profiles supposedly based on a test they had taken earlier. In fact the profiles were composed of statements taken from astrology books, and all the subjects got the same list (see below – number 11 is a particularly good example of a statement that covers all the bases). Asked to “rate on a scale of zero to five the degree to which the description reveals the basic characteristics of your personality”, the subjects gave an average rating of more than four out of five. Forer himself did not mention Barnum; the effect was christened by US psychologist Paul Everett Meehl (1920–2003) in 1956.

Knowing about the Barnum effect is one thing – resisting it is another. Personality psychologists worry about the phenomenon as it threatens to undermine the sometimes-shaky credibility of their discipline. Yet the best advice they can offer is to be aware of the effect and try not to give in to flattery.

Do any of these sound familiar?

[1] You have a great need for other people to like and admire you.

[2] You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.

[3] You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage.

[4] While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them.

[5] Your sexual adjustment has presented problems for you.

[6] Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.

[7] At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

[8] You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations.

[9] You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof.

[10] You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others.

[11] At times you are extroverted, affable and sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary and reserved.

[12] Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.

[13] Security is one of your major goals in life.

Bobo doll

A large inflatable toy, shaped like a ten pin and painted as a clown, with a weighted, round bottom so that it can be punched or kicked over and will bounce back up.

THE BOBO DOLL is famous in the annals of psychological research for featuring in a set of classic experiments by Albert Bandura (b. 1925), in which children apparently showed a tendency to imitate the aggressive behaviours of “models”, whether these were adults in the same room or seen on TV.

Bandura’s social-learning theory suggested that many behaviours are learned through imitation of models, especially parents and other significant adults, but also models in the mass media. In 1961, as a professor of Standford University, he tested this theory with an experiment in which boys and girls aged between three and six years old played with toys in a playroom when an adult came in and started beating up a five-foot Bobo doll. When later given the chance to play with a child-sized, three-foot high version, the children who had observed aggressive “models” were much more likely to beat up on the Bobo doll themselves. Boys were more likely to be physically aggressive than girls and in general the children imitated male “models” more. In a later version of the experiment, children who watched a video of a violent “model” tended to be more aggressive to the Bobo doll.

The Bobo doll experiments are often cited as evidence for the potential impact of violence in TV programmes, films, etc., and also seem to support the theory that children learn how to behave by watching others and imitating or “modelling” their behaviour accordingly. However, within psychology itself the status of these classic experiments is more contentious. Apart from the ethical issues involved, it is also argued that the Bobo doll experiment had poor construct validity, which is to say that the “aggressive” behaviour shown by the children was actually more like rough-and-tumble high-jinks, and that they were smiling and laughing – in other words, Bandura’s experiments didn’t necessarily say that much about aggressive behaviour in the real world. Another way of putting this is that the experiment lacked ecological validity.

Perhaps more serious is the criticism that the behaviour displayed by the children was more the result of the experiment’s “demand characteristics” – that the children were trying to do what they thought the experimenter wanted them to do. Having seen an adult bash the Bobo doll, the children assumed they were supposed to do likewise. Demand characteristics are a major problem area in the design of psychology experiments, and the Bobo doll experiment is a classic illustration. Bobo dolls are still widely available as toys, although today they are better known as “Bop Bags”, so you could repeat the experiment were it not for the ethical considerations and possibility that it is fundamentally flawed anyway.

Brainwashing

Trying radically to change someone’s beliefs or attitudes through coercive and insidious physical and psychological methods, such as sensory deprivation, indoctrination, hypnotism, sleep deprivation, abuse, and even drugs.

THE TERM MEANS DIFFERENT things in different contexts. Today it refers mainly to the process by which religious cults allegedly force new recruits to completely remove themselves from their old lives and utterly embrace a new philosophy or belief system. When the term first appeared in the 1950s and 1960s, however, it was linked to alleged activities of Communists accused of changing the ideology of citizens and particularly American prisoners of war through supposed mind-control techniques.

The term “brainwashing” was coined in 1950 by journalist Edward Hunter, who went on to write a book about indoctrination practices in communist China, Brainwashing in Red China: The Calculated Destruction of Men’s Minds. Hunter claimed that the Communist Party used what they called xi-nao (“wash-brain”) techniques to turn normal citizens into rabid zealots. It later turned out that Hunter was a CIA agent, but whatever his agenda his theories hit the mainstream during the Korean War when American soldiers taken prisoner by the North Korean and Chinese communists were paraded in front of cameras making pro-Communist statements. Even more astonishingly, when the war ended a number of American POWs refused repatriation, apparently preferring to stay in China.

To the American public this was shocking and scary: red-blooded Americans somehow transformed into Commie patsies! Only some form of psychological witchcraft could be responsible – a contemporary commentator noted sarcastically that surely “nothing less than a combination of the theories of Dr I.P. Pavlov and the wiles of Dr Fu Manchu would produce such results”. Brainwashing became cemented in the popular consciousness with the success of Richard Condon’s 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate and subsequent film adaptations, in which an American POW is brainwashed and sent back to America as a “sleeper” assassin, who can be turned into a presidential assassin by a simple code word. Another version of brainwashing in the popular consciousness is Stockholm Syndrome.

MIND CONTROL

Academic theories about the supposed mechanism of brainwashing focused on both sensory deprivation (SD) and over simulation, both of which can be used as psychological torture. The Americans took brainwashing claims seriously enough for the CIA to launch MK Ultra, a decades-long covert programme of research into supposed mind-control technology, which resulted in at least one death and the widespread unethical treatment and abuse of unwitting American subjects.

Psychologists have now concluded, however, that there is no such thing as brainwashing. People can be coerced into acting in a certain way, but they cannot be forced against their will to change their underlying belief structure. The American POWs who resisted repatriation, for instance, may have done so out of fear of being court-martialled for collaboration. Unfortunately, the brainwashing myth still bears fruit in the form of deprogramming, a system of abusive practices similar to those supposedly used in brainwashing, in which deprogrammers “rescue” people deemed to have joined a cult, and attempt effectively to “reverse brainwash” them. Deprogramming is pseudoscientific and unethical, yet even the Encyclopaedia Britannica claims that it “has proved somewhat successful”. Brainwashing is a powerful meme.

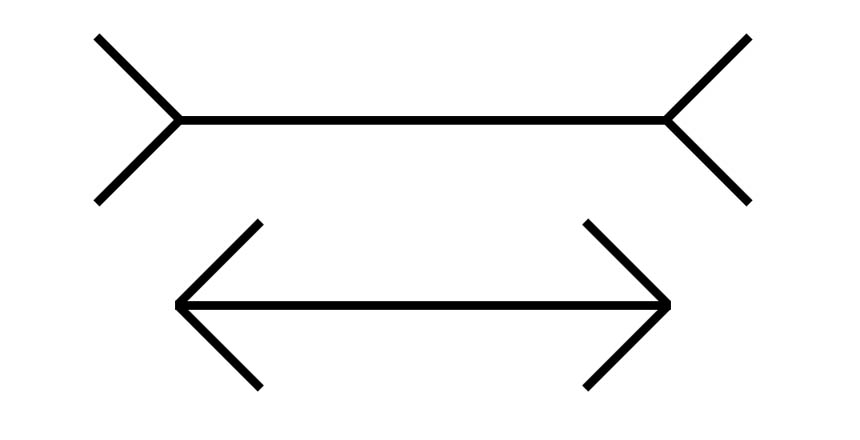

Carpentered environment and the Müller-Lyer illusion

The illusion consists of two parallel lines, one with outward-pointing arrowheads and the other with inward-pointing ones. One line looks longer than the other, but in fact both lines are identical in length. The illusion remains even when you know this.

THE MÜLLER-LYER OR ARROWHEAD illusion is one of the best known and most studied in psychology. First described in 1889 by obscure German psychologist Franz carl Müller-Lyer (1857–1916), multiple theories have since been advanced to explain the illusion. Perhaps the best known is that of Richard Gregory, who suggested that it was the result of top-down processing. This is where the “higher” orders of brain function (such as knowledge and beliefs) impose meaning and even form perceptions, effectively moulding and recombining the raw perceptual data. According to this theory, conscious perceptions are constructs that reflect our preconceptions, biases and expectations as much as reality. In the case of the Müller-Lyer perception, Gregory suggested, we unconsciously interpret the diagonals as perspective cues, as if we were looking at the distant corner of a wall (the outward-pointing arrowheads) or the near corner of the outside of a box or building (the inward-pointing arrowheads). The former therefore seems further away and logically must be longer if it covers the same span on the retina.

Gregory’s theory is somewhat undermined by a version of the illusion that replaces the arrowheads with circles, either right at the tip of the lines or sitting over the ends. The illusion persists, but the circles don’t appear to be giving the same perspective cues. On the other hand, Gregory’s theory appears to be supported by the intriguing finding that the power of the illusion – and therefore the process of perception itself – may be influenced by culture. According to the “carpentered world hypothesis”, first advanced by South African psychologist William Hudson (b. 1914), the illusion only works on people from cultures with built environments full of artefacts constructed from straight lines and right angles (so-called “carpentered worlds”). Tribal cultures in sub-Saharan Africa, such as the Zulu and San, lack such “carpentered” artefacts and so might be expected not to have absorbed the perspective cues apparently at work in the Müller-Lyer illusion. Sure enough, not only do people from such cultures lack two-dimensional representations of three-dimensional objects in their art, but they also appear unable to interpret linear perspective in pictures and are relatively resistant to the Müller-Lyer and related illusions. If it is genuine, the carpentered world phenomenon is a potent illustration of the constructive nature of perception.

Clever Hans

CLEVER HANS, ALSO KNOWN by the German version, der kluge Hans, was a horse that had apparently been trained to understand human speech, do sums, and possibly even read minds. Controlled experiments revealed that the horse was responding to non-verbal cues from questioners in such a way as to mimic comprehension, and this type of experimenter effect is now known as the Clever Hans effect or phenomenon.

Hans was trained by retired German mathematics teacher Wilhelm von Osten (1838–1909) in the city of Elberfeld around the turn of the last century. Hans was introduced to the world in 1901 and amazed all-comers by working out quite complex sums (such as square roots), answering by tapping his hooves the required number of times. The horse performed successfully even in von Osten’s absence, silencing sceptics. Theories advanced to explain Hans’ feats included high levels of animal intelligence and telepathy. Hans was just one of several “Elberfeld horses”, trained in accordance with the theories of Karl Krall, an eccentric but influential animal psychologist whose theories became popular in Germany. Another of the Elberfeld horses, known as Muhamed, could supposedly extract cube roots, critique music and spell words, while an “intelligent” dog trained in the Krall mode was later said to philosophise and appreciate literature.

In 1904, however, Hans was investigated by the psychologist Oskar Pfungst (1874–1932), who employed a variety of clever controls. For instance, Pfungst had one person whisper a number in Hans’ right ear and a second number was whispered into the left ear by someone else – hence the experimenters themselves had no way of knowing the correct sum of the two numbers. In such conditions Hans was unable to perform, for it turned out that all Hans did was tap his hoof until the questioner unconsciously cued how to stop by means of subtle, non-verbal signals such as changes of stance. Pfungst observed that the questioner could produce cues involuntarily and he even identified the precise mechanism involved: when the questioner had finished posing his question and was ready for Hans to start answering, he shifted forwards and looked down at Hans’ hoof. When Hans reached the correct number, the questioner typically straightened up and changed his breathing pattern. Von Osten wore wide-brimmed hats that tended to exaggerate even minor head movements, which probably helped his horses learn to pick up on non-verbal cues.

The Clever Hans effect is of vital importance in studies of animal intelligence and human-animal communication. It continues to plague and confound research into, for instance, the ability of chimpanzees to communicate using sign language. It even plays a controversial role in debates over facilitated communication, a system/therapy for autistic and disabled people who struggle to communicate. In facilitated communication, providing tools such as keyboards, picture boards, and synthesisers seems to allow previously non-communicative people to display much higher intelligence and/or language skills than were previously apparent. But controlled studies of facilitated communication suggest that a form of the Clever Hans effect is at work, with facilitators unwittingly controlling/cueing responses. When facilitators are kept “blind” of the stimuli, the disabled people turn out to be unable to respond appropriately.

Clever Hans-style phenomena, also known as Rosenthal effects, are a major issue in experimental design in general across the sciences. Unless precautions such as double-blind controls (where neither experimenter nor subject are in the know) are taken, experimenters can unconsciously affect outcomes, contaminating results.

Cocktail party effect

At a crowded cocktail party, you are chatting with someone, seemingly oblivious to the hubbub of voices around you, when you notice your name mentioned by someone on the other side of the room.

HOW IS THIS POSSIBLE? You were focused on the conversation with the person next to you, and not listening to the other conversation, which is no louder than a dozen others going on all around you, yet you became aware of the distant conversation as soon as your name was mentioned. This is known as the cocktail party effect or phenomenon, a term coined in 1957 by the British telecommunications engineer Colin Cherry (1914–79).

The obvious implication is that you could hear the other conversation, and that at some level your brain was processing the auditory information involved – i.e. some part of your mind was listening to the other conversation, even though you may not have been consciously aware of it. Since you didn’t know which of the many conversations going on would mention your name, you must presumably have been “listening” to all the conversations at a pre-conscious level of awareness. Interestingly, the effect is much weaker when listening to recorded cocktail party-style conversations. It seems to rely strongly on the stereo nature of binaural (two-eared) hearing, but tone and quality of voice (e.g. whether the voice is male or female) are also important.

The cocktail party effect has important implications for psychological methods of perception, attention, and consciousness. It suggests, for instance, that there are different levels of consciousness, and that you can be more or less aware of sensory input even when not paying full attention to it. But how much processing is going on below the threshold of conscious awareness? To put it another way, to what extent are we not aware of how much we are aware of?

The cocktail party effect may not be all it’s cracked up to be, however. A 2001 study found evidence that the effect may be down too little more than wandering attention. People with high working-memory spans, who are good at maintaining their focus of attention, were much less likely to exhibit the effect than those with low working-memory spans. It seems that the latter group tended quickly to lose focus on the conversation at hand, so that their attention wandered and they had “half an ear” on other conversations. Accordingly they were much more likely to hear their name when it was mentioned in the background. So rather than the cocktail party effect being proof that we can hear (in the sense of automatically, pre-consciously processing) something without attention, it may simply be evidence that most people are not very good at keeping their attention on one thing.

SENSORY PERCEPTION

There are other phenomena that do seem to prove that high-level processing of sensory input is possible without explicit conscious awareness; most notably blindsight. This is where someone (usually after brain damage) claims not to be able to see something but is nonetheless able to point to it.

Cognitive dissonance

Psychological tension arising when someone holds two opposing or clashing cognitions (beliefs, thoughts, or knowledge).

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE THEORY was primarily articulated by US psychologist Leon Festinger (1919–89), growing out of his landmark study, When Prophecy Fails (1956), an account of what happened to a UFO cult when its doomsday prediction did not come true. The cult believed that a great flood was imminent but that the true believers would be rescued by an alien spaceship. When the Apocalypse failed to materialise, the group then claimed that it had been averted because of their faith, becoming stronger believers than ever. This outcome was predicted by Festinger’s theory, which says that when cognitive dissonance (in this case between the belief that the space people were coming and the fact that they didn’t) occurs, people change their cognitions to reduce it (in this case by coming up with a rationalisation for the intergalactic no-shows).

Cognitive dissonance is part of a wider theory, which sees the need to achieve cognitive consistency as one of the primary drivers of human psychology, alongside hunger, sex, etc. Dissonance acts as a sort of feedback mechanism to help maintain consistency. When cognitions cause dissonance, the dissonance in turn motivates us to act to reduce the dissonance. This can be done in one of three ways: changing one of the cognitions (possibly by changing “counter-attitudinal behaviour”), decreasing the perceived importance of dissonant cognitions (i.e. it doesn’t matter that I just betrayed my long-held views on X because actually X is a trivial matter), and/or adding further cognitions (such as rationalisations or justifications).

Another prediction that follows from dissonance theory is that people will act to filter and control their cognitions so as to prevent dissonance arising in the first place, for instance by not reading or watching material that might conflict with their established beliefs and prejudices. Thus, the theory explains, for instance, why liberals in the US tend to get their news from The Daily Show but conservatives only watch Fox.

Cognitive dissonance theory has had a major impact on social psychology, partly because it made predictions that could be tested by experiment and partly because those experiments produced some intriguing and counter-intuitive results. For instance, in a 1959 experiment Festinger and his colleagues showed that the strength of dissonance and resulting cognitive adaptation related to the strength of compliance (the factors forcing the subject into a dissonant state). They got students to do a painfully boring task and then paid them either $1 or $20 to convince another student that it would be fun to do. The subjects who got paid $1 changed their own beliefs about the task, convincing themselves it had been fun; in other words, the less they were rewarded, the more ready they were to lie to themselves. This is known as the less-leads-to-more effect, also called the negative incentive effect, and is contrary to traditional reinforcement theory, which posits people as rational actors. Where reinforcement theory says we dislike things that cause us pain, cognitive dissonance theory says we justify our suffering by convincing ourselves that painful things are better. In another form this is known as commodity theory: goods and products are perceived to have more value when there is a cost attached to them.

However, the concept of dissonance has also been criticised as vague and ambiguous. According to one school of thought, dissonance is nothing more than guilt.

Cold reading

Techniques for convincing a stranger that you can “read” them, using psychic powers, mediumistic communication with spirits, or any other form of anomalous information transfer.

THE TYPE OF READING is labelled as “cold” because the reader comes to the interaction “cold”, as in without any prior information or research. Hot reading, by contrast, involves research such as previous questioning, detective work, or simply googling someone. In both cases the important phenomenon at work is subjective validation, where information supplied by the reader is validated by the subject (aka the sitter) – in other words, the sitter is the one who does all the cognitive work, investing statements with meaning, and supplying answers to questions.

“You’re on the verge of making a big decision in your life…”

Basic cold reading need involve no more than producing a string of statements, and leaving the sitter to make connections and find meaning. More advanced cold-reading techniques make use of a range of verbal and non-verbal feedback from the sitter, such as pupil dilation, breathing rate and posture, as well as Sherlock Holmes-style deduction from their personal appearance, clothes, jewellery, accent, and mode of speech, etc. The feedback helps the reader to proceed from the general to the specific.

Cold reading is the primary device used by psychics, mediums, and mentalists. Not all of them use cold reading cynically or even consciously – there may be many psychics, for instance, who believe in their own gifts and are unaware that they are using cold reading (such cases are known as pious frauds).

Typically, cold reading starts with “fishing” statements: for example, “Is the name ‘Michael’ significant?” – allowing audience members to self-select or prompting sitters to start providing feedback. Cold readers also make use of the Barnum effect (see above), making general and widely applicable statements. Advanced cold readers may use surveys and research statistics to maximise the likely applicability of their statements.

Once a sitter or audience member subjectively validates a fishing statement or question, the reader feeds back the information as a statement, allowing them to claim credit for it. Cold readers make many guesses and ask many questions – only a few need to garner “hits” because of the selective-memory effect. Sitters will only remember the hits, forgetting all the misses. Cold reading is often assisted by the fact that sitters are highly motivated to find meaning and attribute significance, but just as Barnum-style statements work without any contact between author and audience, a cold reading requires no actual interaction between reader and sitter.

Cold reading is also a useful tool for salespeople, and an important factor for other professions to consider. For instance, it is likely that criminal profiles, Rorschach ink-blot readings, and personality inventory tests, all work on similar principles of subjective validation and selective memory.

Culture-bound syndromes

Psychiatric disorders specific to particular cultures, often with no direct equivalent in the West.

SOME MAY BE VARIANTS of what is known today as mass psychogenic disorder (and used to be labelled mass hysteria); some may be culture-specific forms taken by disorders such as schizophrenia; others may be culturally inflected mechanisms for coping with stress. Because culture-bound syndromes (CBSs) reflect indigenous beliefs and superstitions, they seem exotic, strange, and sometimes ridiculous to us, but this reflects an ethnocentric viewpoint.

So far, so exotic, but CBS as a category is not clear-cut. Should it include other forms of mass psychogenic illness, such as witch-hunting panics and other social phobias (for instance, fears in Central American countries that Americans are kidnapping people for their organs, or in South Africa that witch-like prostitutes are hypnotising men and stealing their semen)? If so, should it extend to social panics in the West, such as bogus social workers and satanic ritual abuse? Some psychiatric diseases, such as anorexia, seem to be confined to Western cultures: do they count as CBSs? Meanwhile in some cultural contexts, behaviour and beliefs that would be characterised as deviant or dysfunctional in the West may seem rational or normal, or make sense as a social coping mechanism. CBSs help to illustrate that in some senses psychiatric illness should be defined simply as deviation from a local norm.

EXOTIC SYNDROMES

There are dozens of CBSs, and the same syndrome may have different names in different languages. Among the best-known examples are koro, amok, and windigo. Koro is the Malay language name for penis-stealing panic, which is surprisingly widespread around the world. Koro is marked by fear that some form of witchcraft can lead to shrinking or disappearance of a man’s penis. A single case can lead to a country-wide panic, which in turn can spark off witch hunts that lead to fatal vigilante action. In 1997, for instance, penis-stealing panic spread across West Africa from Cameroon to the Ivory Coast, leading to the murder of at least sixty suspected “sorcerers” at the hands of lynch mobs. In the Far East koro is found from China to Indonesia and can lead to self-mutilation as sufferers attempt to clamp or pin their penises to prevent them shrinking into the body.

Amok is a Malaysian CBS, although it has been reported from Polynesia to Puerto Rico, characterised by a period of intense brooding followed by outbursts of uncontrolled aggression – hence running amok. Wendigo is a strange form of psychosis that traditionally affected Native American tribes around the Great Lakes, especially in winter, in which men would lose their appetite and suffer nausea, followed by delusions of possession by a cannibalistic spirit monster called the wendigo.

Other CBSs include taijin kyofusho, a Japanese disorder characterised by anxiety that one’s personal body and body functions are repugnant and embarrassing; ghost sickness, a Native American syndrome characterised by fear of death, anxiety and panic attacks, traditionally blamed on witchcraft; and pa-leng, a Chinese and south-east Asian fear that coldness and wind can cause impotence, sickness, and death.

Defence mechanism

An unconscious pattern of thought or behaviour that protects the conscious mind from thoughts and feelings that cause anxiety or discomfort.

ALTHOUGH INITIALLY A TERM in psychoanalysis, defence mechanisms are widely recognised by psychotherapy in general. The term originated with Freud, who described defence mechanisms as way in which the ego (the conscious self) protects itself against the id (the unconscious repository of base urges and illicit drives and desires). Defence mechanisms could be described as a form of repression, and as strategies to combat cognitive dissonance. Freud suggested that maladaptive defence mechanisms can turn into neuroses.

From denial to sublimation

Freud and particularly his daughter Anna (1895–1982), in her book The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence (1936), described and explored a great many types of defence mechanism, and several of them are common currency in psychotherapy and popular culture in general:

. Denial: the most straightforward strategy when faced with an uncomfortable feeling or truth is to deny it, such as when a jilted lover acts as if the relationship never ended.

. Rationalisation: coming up with after-the-fact justification for actions or cognitions, such as a drug cheat who claims he had to do it because everyone else did so.

. Projection: projecting negative or difficult feelings about oneself onto others, such as when a bully accuses her victim of being the bully.

. Repression: in psychoanalysis, when problematic feelings or thoughts are banished to the unconscious. In a sense, all defence mechanisms are forms of repression.

. Displacement: taking problematic feelings about one situation and transferring them into another, substitute situation, such as taking out work stress on your family. In psychoanalysis, someone might displace their Oedipal feelings by marrying a girl just like their mother.

. Regression: reverting to behaviour or thinking from an earlier stage in development, typically childhood, when life was simpler and less problematic. For instance, when you react to criticism by having a tantrum or cope with anxiety by cuddling up with an old toy.

. Sublimation: channelling psychic tension into more acceptable outlets. For instance, Freud theorised that the painter Cezanne owed his creative energy to his sublimated sexual desire. Similar theories have been advanced about Isaac Newton.

Déjà vu

The illusion of having previously experienced something that is actually being experienced for the first time, déjà vu is French for “already seen”.

IT IS EXTREMELY COMMON, experienced by up to 80 per cent of people between 20–25 years old, and less commonly with increasing age. Other variants include déjà entendu (already heard), déjà fait (already done), déjà éprouvé (already experienced or tested), déjà pensé (already thought), déjà raconté (already told or recounted), déjà voulu (already desired), and déjà vécu (already lived). This last variant is perhaps the more accurate description of the majority of déjà vu cases, where it is not just the visual aspect that seems familiar.

Déjà vu is generally distinguished by a sense of otherworldliness to the episode, although it is not clear whether this is an integral component of the illusion/delusion, or simply the consequence of knowing that what you are feeling must be illusory. The illusion may be so convincing that you feel you can predict what is about to happen or be said, although there is no record of anyone actually having done so.

From beyond the grave

Alternatively, déjà vu can be seen as evidence for the paranormal. The experiencer may be remembering something, but something from a past life; in other words, déjà vu is evidence of reincarnation. Or you could be picking up someone else’s memory, through telepathy, or have experienced a scene without ever having been there, through some sort of clairaudience. None of these, however, account for the feeling that the event is so familiar you know what is coming next, which suggests that a form of precognition (the ability to know the future) is involved.

Explanations for déjà vu depend on whether you believe the experiencer really has already seen/experienced the event/scene. If so, then what needs explaining is the “first” experience, while the déjà vu itself is simply a form of remembering. It could be that the person with déjà vu has indeed already visited a place/met someone, but cannot remember it, a phenomenon known as paramnesia. In psychoanalysis, paramnesia can be a defence mechanism, indicative that the original occurrence was the cause of distress and hence has been repressed.

Déjà vu is a symptom experienced by sufferers of temporal-lobe epilepsy, sometimes signalling the onset of a seizure. This suggests that the phenomenon has a neurological cause – in other words, it is indeed an illusion, and there is no prior memory causing the sensation. In epileptics, the explanation would seem to be that an anomalous discharge in the temporal lobe creates the illusion of prior memory and/or the overwhelming sensation of familiarity. Something similar may be at work in the general population, related to erroneous activation of the “familiarity” centres.

An alternative neurological explanation is that somehow different parts of the brain become desynchronised (e.g. there is a momentary disruption of communication between the two hemispheres of the brain), causing “splitting” of a perception. Thus, the brain processes the same experience twice, possibly with a microsecond time lag between the two, and this could account for the unsettling déjà vu. Finally, a purely psychological explanation, known as restricted paramnesia, is that the new experience is indeed similar to an actual memory, but one which has been so altered by recurrent reconstruction and elaboration that it triggers a false match.

Less common but still widespread is the opposite of déjà vu: jamais vu. This is where someone is unable to recognise something that should be familiar, such as walking into your own house but not recognising it. Pathological forms of jamais vu characterise conditions such as prosopagnosia, the inability to recognise faces, usually associated with brain damage.

Delusions

A fixed belief that does not make sense given the available evidence, is at odds with the cultural norm, and is resistant to all reason.

DEPENDING ON YOUR POLITICS, everything from climate-change denial to communism could be characterised and/or derided as a delusion, but in a psychiatric sense delusions are peculiar and often disabling ideas at odds with external reality. Delusions are one of the characteristic symptoms of schizophrenia, and are also found in dementia, brain damage, and other conditions. They come in many strange and terrible varieties, but the most common in schizophrenia are delusions of persecution, delusions of reference, and delusions of control.

Forms of delusion

Delusions of persecution involve the conviction that people are “out to get you”, with the focus of the delusion ranging from a plotting neighbour to a global conspiracy. Such delusions are experienced by 65 per cent of schizophrenics, according to a large-scale survey taken in the mid-1970s. Delusions of reference involve the conviction that completely unrelated remarks and references, whether from the media or overheard conversations, relate to you, usually in some negative fashion. Delusions of control involve the conviction that your actions, emotions, and even thoughts are not under your control, but are being controlled by someone else or some external force, whether space aliens, powerful government agencies, evil forces, etc.

Other types of delusion include delusions of grandeur (believing they have special abilities, qualities, or status); hypochondriacal delusions, where you falsely believe you have some illness; nihilistic delusions, where you believe you don’t exist or are worth nothing (common in depression); and delusional jealousy, where you believe someone close to you is persistently unfaithful with everyone.

Cotard’s syndrome is marked by the delusion that parts of your body are rotting or that you have died, apparently combining hypochondriacal delusions with delusions of depersonalisation. Erotomania, also known as Clérambault’s syndrome, is where you develop the delusion that someone else – usually an authority figure/celebrity – is secretly in love with you and is constantly sending subtle signals to that effect, despite explicit denials. The Mignon delusion is a common childhood fantasy that your “real” parents are rich/famous/illustrious and will eventually reclaim you. Fregoli syndrome, named for a famous quick-change artist, is the delusion that multiple different people are actually the same person, who is constantly changing his disguise or appearance. Capgras syndrome is a frightening and tragic condition marked by the delusion that one or more loved ones have been replaced by imposters who look exactly the same.

Delusions can be categorised as monothematic or polythematic. Monothematic delusions have a single theme, such as the delusions of misidentification in Capgras syndrome. Polythematic delusions cover a range of subjects, as in schizophrenics who believe that a global conspiracy against them includes mind-control technology and subliminal messages in the media. Delusions can be bound up together as fully fledged delusional systems.

Disordered perceptions

One theory advanced to explain delusions is that they are an attempt to make sense of disordered perceptions. For example, in Capgras syndrome it may be that while the part of the brain responsible for identifying faces functions normally, the part that assigns feelings of familiarity is malfunctioning. Perhaps in order to explain how they can recognise someone but find them unfamiliar, the sufferer develops the delusion that the person has been replaced. Delusions of control may have a similar basis, in that they could be caused by disruption of the normal experience of conscious volition and initiation that accompanies normal actions and thoughts (which in turn explains the striking observation that sufferers can tickle themselves). If you say something but don’t experience the process of deciding to say it, perhaps the logical conclusion is that an external force is controlling you.

However, explaining delusions as arising from anomalous experience in this fashion fails to explain why delusions are so resistant to logic and cannot be altered or dispelled. Clearly people with delusions must be suffering from some impairment of the ability to evaluate beliefs, perhaps linked to problems with a specific brain region, such as the right frontal lobe.

Dissociation and fugue

Dissociation in a psychological sense is a disconnect between things that are usually associated, such as intentions and actions, events and emotional responses, thoughts and speech, and even between mind and body.

FUNCTIONS AND ASPECTS OF MIND that are normally integrated, such as memory, consciousness and sense of identity, can become dissociated. Ranging from the mild to the severe, examples include driving automatically while thinking about something completely different; feeling nothing in response to an event or memory that ought to provoke sadness or shock; feeling that you are not in control of your actions and you are watching life and yourself from a distance, as if watching a movie; and even forgetting who you are and where you come from. Dissociative disorders can be strange and intriguing, with unsettling implications for consciousness and identity.

Dissociation is a common response to physical and mental trauma or stress, presumably acting as a defence mechanism to protect the self/psyche from unbearable feelings. Approximately seventy-three per cent of people who have a traumatic incident will experience dissociative states during the incident or in the days and weeks that follow. For instance, someone with post-traumatic stress disorder who attends the funeral of a loved one might find that they do not feel grief: they are dissociated from their normal emotional response. Studies estimate that two to ten per cent of the population experience dissociative disorders.

The strangest and most severe dissociative disorders are psychogenic amnesia, fugue, and dissociative identity disorder (DID). Psychogenic amnesia is amnesia with no organic (i.e. physical/physiological) cause, brought on by psychological factors such as stress and emotional trauma. This is the sort of amnesia you see in films such as Hitchcock’s Spellbound. Its most extreme form is the state known as fugue, from the Latin for “flight”, in which the sufferer not only loses memory for his past life and identity, but will travel some distance and set up a new life under a new identity. There is still considerable doubt as to whether psychogenic amnesia, and fugue states in particular, is “genuine” or a form of malingering. For instance, take the case of a man facing bankruptcy whose marriage is also in trouble, who goes into a fugue state, moves to another town and starts a new life under an assumed identity. Is the memory loss genuine, or just an elaborate way of ducking responsibilities?

Even more contentious and controversial is DID, which used to be known as multiple personality disorder (MPD). There was a great vogue for MPD in the early years of psychiatry in late Victorian times, with celebrated cases such as Morton Prince’s treatment of Sally Beauchamp, the subject of a bestselling 1908 book, The Dissociation of a Personality. MPD seemed to prove that there was no unity of consciousness (i.e. no single self), but a number of different streams of consciousness that could dissociate into distinct personalities under pressure. MPD went out of fashion with the supremacy of Freudian psychoanalysis, which suggested that traumatic psychic pressure resulted in repression into the unconscious, rather than separate consciousness, but interest resumed in the 1970s. DID is most commonly found in people who have suffered chronic sexual and physical abuse, especially as children. To cope with the pain and fear, new personalities are created or split off.

Proponents of DID point to amazing evidence, such as different personalities needing different spectacle prescriptions and having different allergies, but critics say that DID may be iatrogenic (created by doctors). “Mythomanic” patients may be confabulating new personalities to meet what they perceive as the demands/wishes of the therapist, especially under the highly suggestible conditions of hypnosis, which is often used as a tool to investigate DID.

But what if DID and fugue are genuine? The legal and philosophical ramifications of extreme dissociative disorders are huge. For instance, who is responsible for a crime committed by one of multiple personalities? Is it fair to punish all the personalities through incarceration of the body they share? Does someone with DID have more than one soul?

Dreams

Images and thoughts experienced during sleep, often occurring in an apparently meaningful sequence, and usually involving emotions.

DREAMS WERE A GREAT MYSTERY to the ancients, who believed they were messages from the gods or the wanderings of the spirit. Today, although we know a little more about dreams they remain a great mystery.

Contrary to popular belief, children under the age of ten do not have a rich dream life, but adults can expect to have four to six dreams a night, lasting from five to thirty minutes each. The vast majority are not remembered. Most dreams happen during a phase of sleep known as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, during which the body is mostly paralysed but the mind is almost as active as when you are awake.

Dream content can vary enormously, but the most common dreams involve strong emotions – mostly negative ones, such as fear and anxiety. The most common dream theme is being chased or followed, and dreams usually feature the dreamer as him/herself, along with other known/familiar people.

These facts suggest some explanations for dreaming while appearing to rule out others. For instance, REM sleep is “expensive” in terms of energy use, so there must be a good reason for dreaming to occur, or evolution would have weeded it out. But what function could dreams serve?

Dreams are of central importance to the theories and practice of psychoanalysis. Freud wrote that “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind”, while Jung believed that dreams gave access to the archetypes of the collective unconscious (see above, Archetypes and the collective unconscious). According to psychoanalysts, dreams rehearse repressed desires and unfulfilled wishes, helping the conscious self or ego deal with the problematic content of the unconscious. If this is true, however, why do we forget around ninety-nine per cent of our dreams? Wouldn’t it be more helpful to remember them?

Another explanation is that dreams evolved as a form of simulator, allowing us to rehearse survival strategies in a sort of virtual-reality environment. This might help explain why negative emotions and pursuits are so common in dreams: they help us rehearse coping with dangerous and stressful situations.

Ego, superego, and id

From the Latin for “the I, the super-I, and the it”, the ego, superego, and id make up Freud’s tripartite (three-part) structure of personality, also known as the structural hypothesis/model/theory.

AT FIRST FREUD HAD DIVIDED the mind up according to its topography (which is to say, the layout of mental space), with the unconscious, preconscious, and conscious. But in 1920, with his structure of personality, Freud articulated not only a model of personality but also an account of its development.

The id is the part of the mind that contains the inherited, biological, “animal” instincts (which Freud said included Eros, the sex/life instinct, including the libido, and Thanatos, the death instinct, responsible for aggression). It is motivated by the pleasure principle, which demands instant gratification, from which it derives pleasure, and when it is thwarted it experiences un-pleasure, or pain. The id is not affected by logic or reality, taking no account of the external world. A newborn child is all id.

As the child matures the demands of the id come into constant conflict with the realities of the external world, and the part that has to deal with reality becomes the ego. The ego works on the reality principle, which involves working out how realistically to meet the demands of the id, delaying or compromising gratification in order to achieve pleasure and avoid pain. The ego is rational but without morality or ethics it is purely practical.

Morality comes into the picture via the superego, which absorbs the values and morals of the family and wider society and works to control the impulses of the id, especially those which are taboo, such as lust and aggression. The superego includes the conscience, which punishes the ego with guilt when it transgresses the moral rules or gives in to the id, and the ideal self, which combines the aspirations and ambitions set out for the individual by family and society. Failure of the ego to live up to the ideal self also leads to guilt, but “proper” behaviour can be rewarded with pride. An overbearing superego and especially an unrealistic ideal self can cause neurosis, anxiety, and depression. In the adult, the id is entirely unconscious, while the superego and the ego extend from the conscious down into the unconscious.

The whole system is supposed to be self-correcting, working via feedback loops based on the principle of tension reduction – seeking the path of thought and behaviour that gives rise to the least psychic tension. Freud himself used the analogy of a horse and a rider for the id and the ego, and given the rather gloomy narrative of tensions, drives and motivations offered by Freud, it is tempting to extend the analogy and imagine a hapless rider clinging onto a careering horse, maddened by lust and greed and kept in check only by the sting of the spur and the whip. “The poor ego,” wrote Freud in 1932, “has to serve three harsh masters, and it has to do its best to reconcile demands of all three . . . The three tyrants are the external world, the superego, and the id”.

LOST IN TRANSLATION

The Latin-based/common-usage terms “ego” and “id” point to a recurring issue with the translation of Freud’s work. Freud himself, for all that he was concerned for psychanalysis to be taken seriously as a science, for the most part avoided technical jargon and obscurantism. His English translator, James Strachey, however, often chose terms that sounded more technical, perhaps partly to increase their “scientific” authoritativeness. Ego and id are classic examples; in the original German, Freud calls them simply das Ich Es, the “I” and the “it”.

Perhaps in reaction to this jaded view of human nature, Freud’s daughter and other successors developed a more humane spin on his model of the self, in the form of ego psychology. Ego psychology argued that the ego was not defined by its constant internal battle with the id and superego, was not governed solely by the need to reduce tension, and could be motivated by positive feedback loops such as seeking novelty and mastering new skills.

Electroconvulsive therapy

Also known as shock therapy or electric shock therapy, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) involves stimulation of seizures or convulsions similar to those experienced by grand mal epileptics, by means of applying an electric current across the head.

IN MODERN ECT, A pair of electrodes, which look a bit like headphones, is fitted over the temples and a weak electric current (20–30 mA) is applied, triggering a seizure. Light general anaesthetic and muscle relaxants have already been administered, so the seizure does not actually involve convulsions. In the early days of ECT before anaesthesia and relaxants were used, convulsions could lead to broken bones and other injuries. A course of treatment typically involves six to twelve shocks over a number of weeks, with side effects including disruption of heart rate, headaches, and memory loss.

One of many points of uncertainty and contention about ECT regards the inspiration for its first use by Italian neurologist Ugo Cerletti (1877–1963) in 1938. According to one account, Cerletti got the idea from watching pigs being anaesthetised by electric shock before being butchered, while according to another account he believed (erroneously) that epilepsy and schizophrenia did not occur together, and hence inferred some anti-psychotic effect of seizures. A third version is that Cerletti was aware of an observation that people with epilepsy and depression displayed improvements in mood after a seizure, and again inferred that seizures themselves could have some therapeutic effect. Whatever the initial inspiration, it became apparent that ECT did indeed produce rapid improvements in mood, even in suicidally depressed patients.

ECT is not the only form of shock therapy – the drugs insulin and Metrazol have also been used to trigger seizures, but these methods had lower success rates and are more dangerous than ECT and are no longer used.

SHOCK HORROR

ECT is a controversial treatment, which has had a bad press since the days when it was applied without anaesthetic, and as a result of its alleged use in some institutions as a threat and punishment to keep difficult patients in line. Controversy extends to the clinical evaluation of ECT – doctors and psychiatrists disagree fiercely over how safe it is, when it should be used, and even whether it works at all. Some studies show that, in the treatment of very severe depression and schizophrenic catatonia, ECT is more effective with fewer harmful side effects compared to drugs. Other studies, however, seem to show little benefit over placebo treatments, and potentially very severe, long-term damage to memory and brain function.

Perhaps the biggest problem with ECT is that even if you accept that it does work, no one knows how or why. It seems that it is not the shocks themselves that are therapeutic, but the seizures induced. Seizures appear to affect levels of neurotransmitters (chemicals that pass signals between nerve cells) in the brain, boosting some and increasing the effect of others. It may also be that seizures cause the brain to release opium-like painkillers called enkephalins, which may account for the mood-boosting effects of ECT.

Emotional intelligence and EQ

Emotional intelligence (EI) is seen either as a subset of intelligence in general, or as a parallel system of mental abilities alongside rational intelligence.

SINCE THE SUCCESS of Daniel Goleman’s 1995 book Emotional Intelligence, EI has been a hot topic both in psychology and in the wider world, especially because of its applied nature. EI seems to play at least as big a part as general intelligence in terms of managing and being successful at your career, relationships, and life.

The concept of EI predates Goleman. An appreciation of emotion as a core cognitive competence – which is to say, a mental skill/ability that helps us to function better or, in the case of animals, survive, goes back to Darwin.

In 1920 American psychologist E.L. Thorndike wrote about social intelligence, while in the 1970s Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences included inter- and intrapersonal intelligence. Peter Salovey and John D. Myer introduced the term EI in the modern sense in 1990.

There are several different models or theories of EI, but all stress a kind of hierarchy, with basic skills or “competencies” such as being able to recognise emotion in yourself and others; being able to regulate and manage emotions in yourself and in your relationships with others; and being able to put your emotional skills to work in a variety of ways, such as problem solving or adapting to change. The definition of EI has been extended to include aspects as varied as morality, persistence, and enthusiasm.

But amidst these competing models with their multitude of competencies and attributes there is considerable confusion. Partly this could be down to confusion between two types of EI and the two ways used to measure them. Measurements of EI are sometimes labelled as Emotional Quotient or EQ, to stand alongside IQ. But because emotions are mostly subjective, most measurements of EQ have been done using self-report questionnaires, which don’t meet the same objective criteria as IQ tests (composed of questions with right or wrong answers). Accordingly, EI researchers K.V. Petrides and Adrian Furnham suggest that most EQ tests are actually measuring what they call “trait EI”, which describes the role of EI in personality. Also available are IQ-style tests that are supposed to measure “ability EI”, which describes the role of EI in cognition (thinking and reasoning).

A key question in the EI field is the extent to which people can boost their EQ. There are lots of programmes – particularly in the business world – that claim to teach EI skills and boost EQ. Whether this is really possible is an open question; perhaps it is necessary to focus more on “emotional education” from an early age to improve “emotional knowledge”, to complement the more traditional version of knowledge.

Erikson and the eight ages of man

ERIK ERIKSON (1902–1994) is one of the most significant figures in post-Freudian psychoanalysis. His “psychological theory”, known as the eight ages of man, has had a profound and enduring influence on both psychology and wider popular culture.

Erikson went to art school and worked as a teacher before falling into the orbit of the Freud family and the Vienna Psychoanalytic Institute. He was particularly interested in child development, but what marks out his best-known contribution to psychology, his psychosocial theory, is its emphasis on the whole life cycle.

With others, Erikson developed ego psychology, a more positive view of the structure and function of the psyche than Freud’s version. Ego psychology stressed the capacity of the ego for autonomous action, and the role of interaction between the individual and the environment/society in shaping human psychology. His psychosocial theory was more humanistic still, viewing the conflicts facing the ego as opportunities for change and growth, as well as potentially dangerous crises.

The Eight Stages of Man

The theory sets out what Erikson called the development crises facing an individual at certain stages in life from childhood to old age. At each stage a person must resolve a conflict between opposing forces or drives, and either acquire specific “ego virtues” or suffer psychic damage as a result. The stages are:

[1] basic trust versus basic mistrust, in early infancy; successful resolution leads to hope

[2] autonomy versus shame and doubt, in later infancy; leading to will

[3] initiative versus guilt, in early childhood (preschool); leading to purpose

[4] industry versus inferiority, in middle childhood; leading to competence

[5] identity versus role confusion, in puberty and adolescence; leading to fidelity

[6] intimacy versus isolation, in young adulthood; leading to love

[7] generativity versus stagnation, in mature adulthood; leading to care

[8] ego integrity versus despair, in late adulthood; leading to wisdom.

Some of the concepts Erikson introduced around this scheme have become common currency in popular culture, particularly the identity crisis experienced by adolescents figuring out their role in life. Others deserve to be better known, for instance, the “psychosocial moratorium”, a sort of time out from progress through the stages during which a person keeps a fluid identity, such as when a young person takes a year out after university to travel before slotting into the more constrained route of career and family.

Erikson anticipated a number of modern concerns that keep his theories contemporary and valid. He described his model as epigenetic, meaning that while the sequence of development was preprogrammed by our biology (i.e. our genes), progress through the sequence depended on the interaction between our biology and our environment. In stressing the continuous nature of development throughout life he offered a more forward-looking model of human psychology, and thus a more hopeful approach than Freud’s gloomy mire of unconscious complexes fixed in the inaccessible and immutable past. In fact Erikson has been criticised for his perceived overoptimism, as well as for the subjective anecdotal nature of his evidence.

False memory

A false memory is either a distorted recollection or an entirely imaginary one.

FALSE MEMORY IS SURPRISINGLY COMMON. The typical analogy between encoding of memory and filing away a document, and particularly between recall and retrieval of a document from a filing cabinet, a book from a library or webpage from the internet, is misleading. Memory is a reconstructive and sometimes purely constructive process. In a sense, all memories are false in that they are not objective duplicates of events and experiences.

False memories can be created in a number of ways. When a memory is constructed from incomplete memory fragments, vital elements of the memory can be transposed or introduced. For instance, you might remember a conversation but get the speakers the wrong way round. In one notorious incident a woman who was raped accused a memory expert of being responsible because she had seen him interviewed live on television just before the rape. Memories can also be entirely confabulated, and they can be introduced through suggestion, particularly in impressionable states like hypnosis, or in highly suggestible individuals such as young children and fantasy-prone personalities. All of these processes can be triggered and guided through questioning, hypnosis, and the like.

False memory can be experimentally induced; in fact, it is extremely easy. One classic experiment revealed the misinformation effect, which is where misinformation supplied to someone becomes incorporated into their recall. Two groups were shown a video of a traffic incident, and one of the groups was given misinformation in the form of a leading question: “Did you see the red car pass the white one when it was waiting at the stop sign?” There had been no stop sign, but many subjects falsely remembered one. Providing misinformation has been shown to make people half as accurate as they would have been without it, and post-event misinformation has introduced false memories varying from a clean-shaven man having a moustache, to the presence of a large barn in a photo of an empty country landscape.

Other experiments have proved that false memories for entire scenes and traumatic events can be implanted in people’s minds. One study convinced people they could recall being lost in a shopping mall as children, while another implanted memories of being attacked by an animal. The classic example from psychology is the false-kidnapping memory of child development pioneer Jean Piaget. As a very young child his nurse claimed to have beaten off an attempt to kidnap him, and he could recall the incident in some detail. She later admitted it had never happened.

Extreme cases such as this are known as false memory syndrome (FMS), a phenomenon which has had serious and sometimes tragic clinical, legal, and social consequences. Leading interview techniques and the use of hypnotic memory recovery has led to wholescale confabulation of memories for childhood sex abuse, satanic ritual abuse, and alien abduction. FMS is primarily to blame for the entire alien abductee phenomenon, and for sex-abuse panics that have destroyed families and homes.

PAST LIFE REGRESSION

FMS is also probably the explanation for past life regression, which is where someone under hypnosis claims to remember detailed scenes and events from a past life. Past life regression became famous thanks to the success of the 1956 book The Search for Bridey Murphy by Morey Bernstein, which detailed how the hypnosis of Virginia Tighe “recovered” memories of a past life as a poor Irish woman in the nineteenth century, complete with apparently authentic stories, songs, and biographical details. Newspapers later discovered that there was no record of any such woman in Ireland, but that Tighe had lived opposite a Bridey Murphy as a child. Her past life “memories” were the result of paramnesia and hypnotic suggestion colliding to produce FMS.

Freud

REGARDED BY MANY AS the greatest thinker in psychology and perhaps the pre-eminent genius of the twentieth century, Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) is also damned as a pseudoscientist and false prophet. Paradoxically his status and that of his theories is higher outside of psychology than within.

Freud was an Austrian Jew who trained as a doctor, specialised in neurology, and published research in neurobiology. He also narrowly missed out on discovering the anaesthetic properties of cocaine (although he did succeed himself in becoming addicted for a period). Anti-Semitism limited his job opportunities and directed him into psychiatry, and he trained with leading figures such as Jean-Martin Charcot in Paris and Josef Breuer in Vienna. Their reliance on hypnosis, and Breuer’s emphasis on hypnotic revelation of suppressed thoughts and emotions, helped lead Freud to formulate a psychological theory of personality disorders, and of personality itself.