– ‘Science Book: Astronomy’ seeks to address all of the fundamental concepts within the field of Astronomy.

Introduction

Astronomy is the scientific study of everything in the universe beyond Earth’s atmosphere and examines their chemical and physical properties. It includes objects we can see with the human eye like the Sun, the Moon, the planets, and the stars. It also includes objects we can only see with telescopes or other instruments, such as faraway galaxies and tiny particles.

The study of astronomy uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry, to explain the origin and evolution of celestial objects and phenomena. It is a physical science concerned with the smallest particles and the largest natural objects. The name Astronomy comes to us from its Greek roots Astr– and –nomia to literally mean “name stars”.

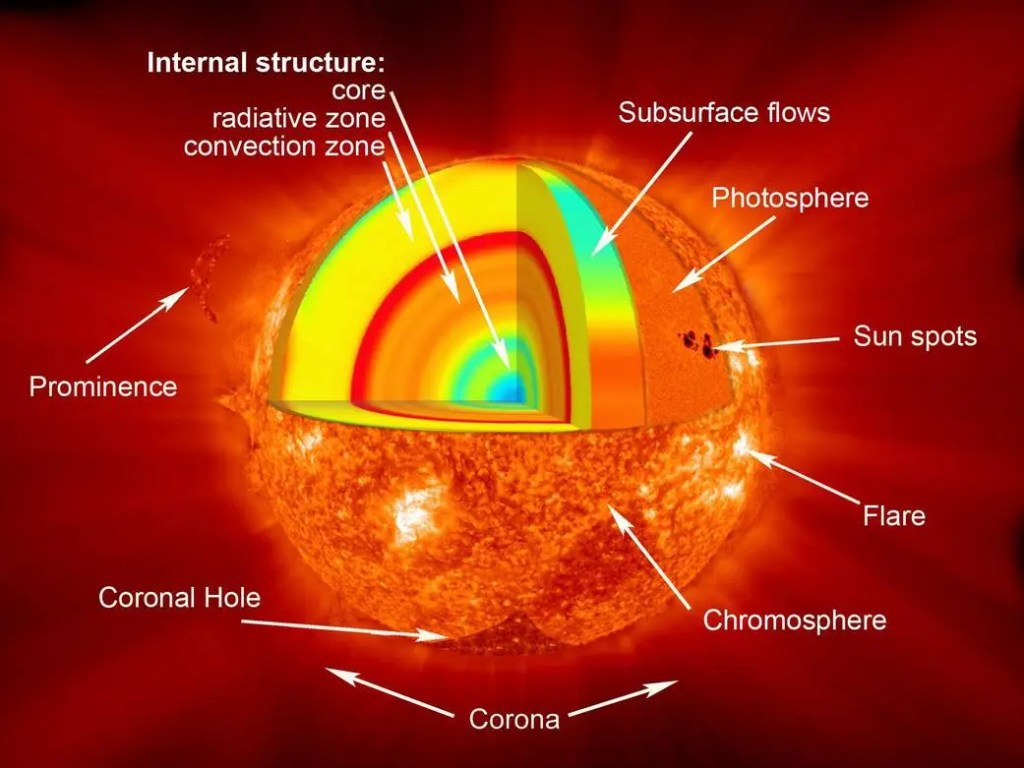

The Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of our solar system. It lies about 150 million km [93 million miles or 8.3 light minutes] away from Earth and has a diameter of 1,391,000 km [864,300 miles]. The Sun’s composition is almost three-quarters hydrogen, roughly one-quarter helium [by mass], while heavier elements make up less than 2 per cent.

The Sun generates energy by nuclear fusion of hydrogen in its core. Heat moves out to the ‘photosphere’, where the sunlight we see originates. Beyond that a thin ‘corona’ expands outwards to form the solar wind, a stream of particles that constantly blows out into space. Sunspots are temporary, relatively cool patches on the Sun where magnetic fields have suppressed heat transfer to the surface.

The Sun formed a collapsing gas cloud about 4.57 billion years ago. Around 5 billion years from now, it will expand into a red giant star, its outer layers engulfing the planets Mercury and Venus, and possibly the Earth. Eventually, it will shrink into a hot and dense white dwarf.

[1] Core generates energy through nuclear fusion

[2] Radiative zone transports energy by radiation

[3] Convective zone transports energy through convection

[4] Photosphere where gas becomes transparent

[5] Superhot outer atmosphere or corona

The Moon

The Moon is Earth’s only natural satellite. It lies 384,400 km [238,900 miles] away from the Earth on average, although the distance varies by about 5 per cent during the Moon’s 27.3-day orbit. The Moon has one-eightieth of the mass of the Earth. Viewed from Earth, it goes through phases as reflected sunlight makes different portions of it visible.

Our satellite is thought to have formed about 4.53 billion years ago, when a Mars-sized body smashed into the newborn Earth, spewing hot debris out into Earth orbit. The debris subsequently clumped together into the Moon, which gradually cooled. Today, it has a layered interior structure, probably with a small, partially fluid core.

Over time, the Earth’s gravitational pull on the Moon has forced it into ‘synchronous rotation’, rotating once for every 27.3-day orbit so that one side faces permanently towards Earth. The surface is pockmarked with millions of craters, more than 5,000 of which are larger than 20 km [12 miles] across. Most formed from the impact of comets and asteroids.

Eclipses

Eclipses are astronomical events that occur when one body passes in front of another and blocks out its light. The most spectacular ones are total solar eclipses, which occur when the Moon lines up with the Sun, as viewed from Earth. The Moon blocks out the sunlight, briefly turning day into night.

Chance alignments between Earth, Moon, and Sun create up to two total solar eclipses each year, visible from limited region of Earth’s surface. Because the Sun and Moon appear the same size in Earth’s skies, the Moon can obscure the Sun for several minutes. Partial solar eclipses occur when the Moon blocks only part of the Sun.

Total lunar eclipses occur when the full Moon moves into the Earth’s shadow and is no longer illuminated by direct sunlight. The Moon appears dark red due to some sunlight reaching the lunar surface after refracting, or bending, through the Earth’s atmosphere. The word ‘eclipse’ can also refer to the apparent coincidence of more distant bodies – for instance, one start briefly blocking the light of a companion star orbiting around it.

[1] Sun lies 150 million km [93 million miles] from Earth

[2] Moon passes across face of Sun as seen from Earth

[3] Umbra: a region of total eclipse

[4] Penumbra: region of partial eclipse

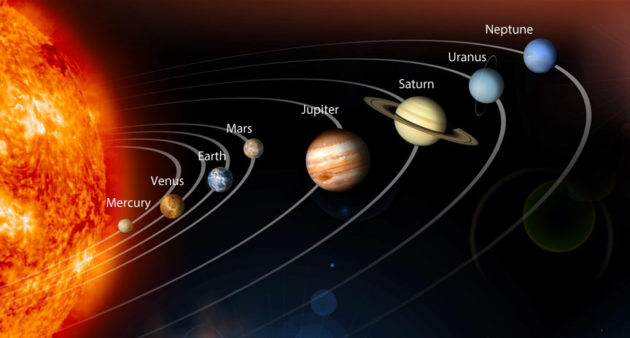

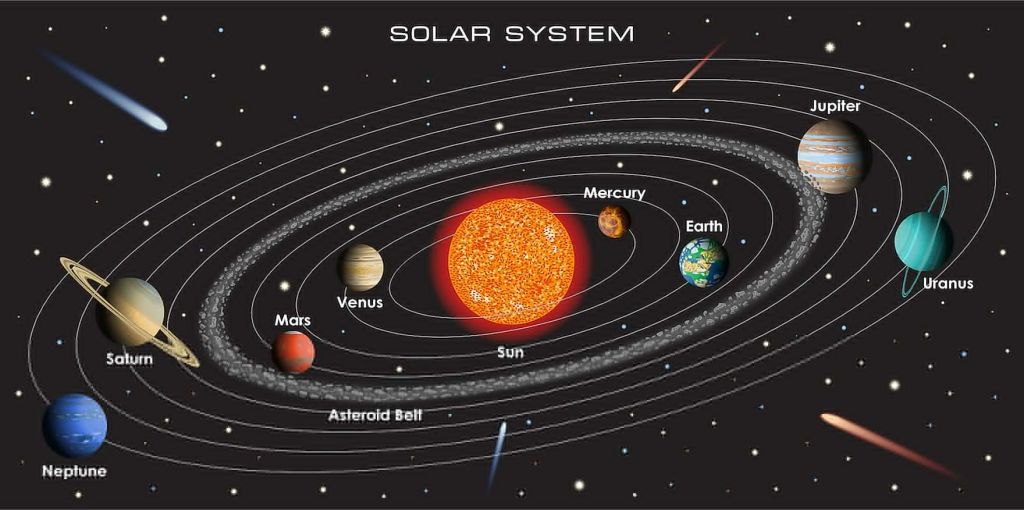

Planets

The solar system has eight planets: the four terrestrial planets Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, and the giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. They all formed about 4.54 billion years ago, when material clumped together in a disc of gas and dust around the Sun.

Rocky terrestrial planets formed in the warm inner solar system, which favoured compounds with high melting points such as metals and silicates. The giant planets lie beyond the ‘frost line’, where volatile compounds formed ices that clumped into larger balls capable of capturing heavy atmospheres.

The orbital distances of the planets are measure in astronomical units [AU], where 1 AU is the Earth-Sun distance. A simple numerical relationship called Titius-Bode law predicts the orbit distances. It starts with 0 followed by the doubling-number sequence 3, 6, 12 etc., then adds four to each and divides by ten. The resulting sequence closely matches the planetary orbit distances [with the exception of Neptune], but there’s no physical reason for this – it’s just a coincidence.

Terrestrial planets: Mercury to Mars

Mercury is the planet closest to the Sun. It orbits the Sun every 88 days and rotates very slowly so that a Mercury day – the time between one sunrise and the next – is 176 Earth days. Temperatures during the long days can climb to 450°C [849°F] on the planet, which has almost no atmosphere, while night chills the surface to –170°C [–274°F].

Venus is the second planet, orbiting the Sun in about 225 days. It’s similar in size to Earth but is often described as the Earth’s ‘evil twin’. It has a crushing, heavy atmosphere of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas, which bakes the surface to 465°C, as well as dense clouds of sulphuric acid.

The Earth is the Sun’s third planet, followed by Mars, which takes 687 days to orbit the Sun. Today, the average temperature on this chilly planet is about –60°C and the atmosphere is thin and dry, but there are large deposits of ice buried below the surface, and ancient surface features such as riverbeds suggest that Mars was once warm enough to have water, oceans, and flowing rivers.

Outer planets: Jupiter to Neptune

The four outer planets of the solar system are vast worlds that together contain almost 99 per cent of all the matter orbiting the Sun. The largest is Jupiter, which is more than 11 times wider than the Earth. Jupiter orbits the Sun every 11.9 years and is famous for colourful banded clouds and the Great Red Spot, a giant storm that has persisted for at least two centuries. Jupiter has dozens of moons including Ganymede, the largest moon in the solar system.

Saturn, like Jupiter, is a gas giant mostly composed of hydrogen and helium. It orbits the Sun every 29.5 years and sports the most magnificent example of an orbiting ring system, packed with ice chunks, some as large as a bus.

Beyond Saturn lies Uranus and Neptune, with orbital periods of 84.3 and 164.8 years respectively. They are often classed as ice giants because they are richer in ices such as water and ammonia than the gas giants. Uranus’s rotation axis has a curiously high tilt, so it effectively rotates ‘on its side’ compared to Earth.

Dwarf planets, asteroids, and comets

Broadly speaking, a dwarf planet is a medium-sized world roughly 2,000 km [1,200 miles] wide that orbits a star. The term’s precise definition is convoluted, but in our solar system, five known bodies qualify as dwarf planets. They include Pluto, which was classified as a planet until it became clear that there are many similar-sized bodies in the outer solar system; the category ‘dwarf planet’ was introduced in 2006 to unite them.

Asteroids are smaller than dwarf planets. These rocky chunks mainly circle in the ‘asteroid belt’ between Mars and Jupiter, although a few have elongated orbits, some crossing the orbit of Earth. Astronomers carefully monitor them to find out if they risk striking the Earth in future, perhaps even causing a mass extinction.

Comets are big, dusty snowballs that venture in towards the Sun from two chilly reservoirs of icy bodies – the ‘Kuiper belt’ beyond Neptune and the more distant ‘Oort cloud’. As they approach the Sun and heat up, comets sprout fuzzy atmospheres of gas and dust, and sometimes a long tail.

Heliosphere

The heliosphere is a vast bubble carved out in space by the solar wind. This bubble envelops all the solar system planets, with its outer boundary marking the region where the solar wind ‘loses its puff’ and interstellar space begins.

The solar wind blows past all the planets at supersonic speeds of more than 1 million km/h [621,000 mph] before slowing down as it encounters resistance from interstellar gas. The point where it slows below its speed of sound is called the termination shock. Two NASA spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, crossed this shock at distances of about 94 and 76 astronomical units [1 AU is the Earth-Sun distance]. The shock is probably irregularly shaped and constantly moving.

Beyond this lies the ‘heliopause’, the theoretical boundary where the interstellar medium brings the solar wind to a halt. Beyond this is the ‘bow shock’, where the interstellar medium hits the outer heliosphere at high speed due to the Sun’s orbital motion around the Milky Way.

Stellar evolution

Stellar evolution describes the way stars change as they age. Stars form when clouds of gas collapse under their own gravitational pull, and the biggest factor in a star’s destiny is its mass. The most massive stars live fast and perish young, blowing up in supernova explosions after only a few million years, while theoretically the smallest ones can shine for hundreds of billions of years.

The Sun is a medium-mass star, which will live for about 10 billion years. It is about halfway through its lifespan, spent mostly in a phase called the ‘main sequence’, during which it generates energy through hydrogen fusion in its core.

Astronomers chart the main stages of stellar evolution on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, which plots the colour of a star against its magnitude or luminosity [a measure of its brightness] to reveal patterns. Stars can end their lives in different ways. The Sun will end up as an extremely dense white dwarf, a hot ball of matter roughly the size of the Earth that will gradually cool and fade.

Main sequence of stars burning hydrogen in their cores – positions along line depends on mass of star.

Red and orange giants are expanding bright stars near the end of their lives.

Most massive stars swell into supergiants as they age.

White dwarfs are hot but faint cores left behind when Sun-like stars burn out.

Supernovae

The most powerful explosions in the Universe

A supernova is a brilliant explosion in which a star blows itself to smithereens. ‘Core-collapse supernovae’ signal the death of stars more than eight times as massive as the Sun. Fusion reactions gradually build up heavy elements in their cores, but when the fuel runs out, there isn’t enough outward pressure to prevent the core suddenly collapsing, sometimes into a black hole. This triggers an outward shock wave that catastrophically blows the star’s atmosphere apart.

A related phenomenon is the gamma-ray burst, a powerful blast of gamma rays that satellites have detected since the 1960s. Most of these bursts are thought to signal extremely massive, rapidly rotating stars collapsing into black holes.

‘Type la’ supernovae are another main supernova class. They occur when a small, dense white dwarf star grows more massive, either because a companion star ‘feeds it’ with matter, or because two white dwarfs merge. When the total mass reaches about 1.38 times the mass of the Sun, the star becomes unstable and collapses with a huge release of energy.

The five stages of a supernova:

[1] The star runs out of fuel and its core becomes unstable.

[2] The core collapses under its own weight in less than a quarter of a second, releasing a huge amount of energy.

[3] The energy creates a shockwave that travels to the surface of the star, blowing off its outer layers.

[4] The supernova becomes very bright and emits a flash of light that can outshine a galaxy.

[5] The supernova fades away over months or years, leaving behind a remnant such as a neutron star or a black hole.

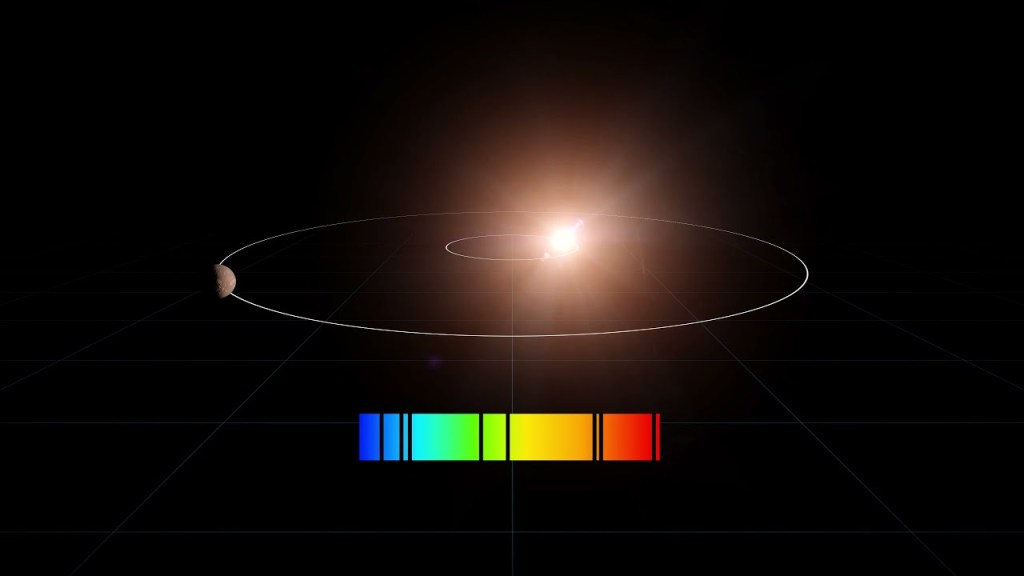

Extrasolar planets

An extrasolar planet, or exoplanet, is a world that circles a star beyond our Sun. More than 500 exoplanets have been discovered in our galaxy since the mind-1990s, suggesting that other planets are common throughout the universe.

Most of these worlds have been detected by the ‘radial velocity’ technique. Astronomers use the Doppler effect (see Science Book: Physics) to test whether a star is wobbling back and forth due to the gravity of an invisible orbiting planet. Other planet-hunting techniques include the ‘transit’ method – looking for a slight dimming of a star when a dark planet passes in front of it. A handful of exoplanets have been imaged directly.

Many exoplanets found so far are very unlike the planets of the solar system. Some are ‘hot’ Jupiters, giant planets that zoom round their stars in just a few days, others are ‘super-Earths’, rocky worlds several times as massive as Earth. Surprisingly, some exoplanets orbit neutron stars. The holy grail is to find potentially habitable planets similar to Earth orbiting ‘normal’ stars like the Sun.

[1] An inner shining star.

[2] Orbiting external planet.

[3] Star and planet both orbit their shared centre of gravity so the star ‘wobbles’.

[4] Change in apparent position of the star is too small to detect from Earth, but back-and-forth wobble can be measured from the Doppler shift of its light.

The Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy of stars that hosts our own solar system. It’s a magnificent example of a large spiral galaxy, containing roughly 400 billion stars.

Most of the Milky Way’s stars lie within a structure shaped like two fried eggs back-to-back. A vast disc of stars [the egg whites], roughly 100,000 light years wide, has a central starry bulge [the yolks] with a supermassive black hole at its centre. The disc has several bright spiral arms where dense gas fuels vigorous star formation. Our own solar system lies in the disc, about 26,000 light years away from the galactic centre, which it orbits every 230 million years.

The Milky Way’s disc is surrounded by a large spherical halo containing old stars and tight-knit balls of stars called globular clusters, while the whole galaxy is embedded in a vast cloud of invisible dark matter. Sometimes, the term ‘Milky Way’ is used to mean the dense band of stars that crosses the sky where we look across the plane of the galactic disc.

Features of the Milky Way galaxy

Galaxy types

Galaxies are groups of millions or billions of stars bound together by their mutual gravitational pull. They also contain interstellar gas and dust, as well as vast quantities of dark matter.

Galaxies come in three main types. Spiral galaxies, including our home galaxy the Milky Way, have a disc of stars threaded by spiral arms where vigorous star formation takes place.

Elliptical galaxies, which include the most massive known galaxies, are spherical or oval in shape. Galaxies that don’t have a spiral or elliptical shape are classified as ‘irregular’.

Galaxies frequently collide, their gas and dust sometimes combining to trigger vigorous star formation in a new ‘starburst galaxy’. Active galaxies emit enormous amounts of radiation, but most galaxies are dim dwarfs containing less than a few billion stars. Galaxies mill around each other in clusters bound by their mutual gravitational attraction, while clusters congregate in ‘superclusters’ spanning several hundred million light-years.

The Hubble ‘tuning fork’ model of galaxy classification

[1] Elliptical galaxies are classified from E0 to E7 depending on how spherical or flattened they are.

[2] Lenticular galaxies have a spiral-like hub and disc, but no spiral arms.

[3] Normal spiral galaxies are classified from Sa to Sc according to the tightness of their spiral arms.

[4] Barred spiral galaxies, classified from SBa to SBc have a bright straight bar of dense stars in the centre.

Active galaxies

Active galaxies have bright cores that emit amazingly large amounts of radiation, outshining all their stars. They are so bright that we see them at enormous distances, sometimes so far away that their light has taken more than 13 billion years to travel to Earth.

They are thought to contain supermassive black holes in their cores, which feed on stars and interstellar gas spiralling towards them in a swirling disc. This matter becomes searingly hot as it swirls inwards, so that it emits extremely intense radiation. At the same time, two energetic jets of particles emerge perpendicular to the disc, blasting out across thousands of light-years of space.

Active galaxies fall into different categories, including quasars, Seyfert galaxies and blazers, which have different patterns of light emission. However, astronomers suspect that they’re all similar objects viewed from different angles. For instance, blazers are probably the subset of active galaxies that have one of their jets pointed directly towards Earth.

[1] Surrounding ‘host’ galaxy.

[2] Central black hole draws in material.

[3] Accretion disc of superhot material around black hole forms quasar.

[4] Jets of material escape above and below quasar.

[5] High-energy particles in jets emit bright radiation.

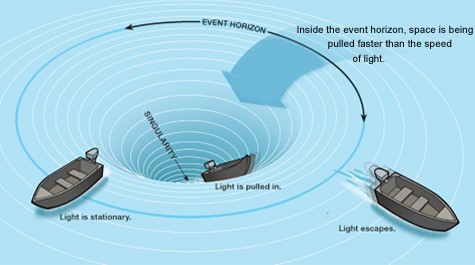

Black holes

Black holes are dark voids in space from which nothing – not even light – can escape. A black hole can form when a very massive star dies in a supernova explosion [see above], leaving behind a dense core so heavy that it can’t support its own weight. It collapses to a tiny point of enormous density with an immense gravitational pull.

Black holes have a theoretical boundary around them called the event horizon, which marks the point of no return. The size of a static black hole’s event horizon is proportional to its mass. The dark, inescapable region of a 10-solar-mass black hole would be roughly 60 km [37 miles] wide.

Much heavier black holes lurk at the centres of large galaxies. They have masses thousands to billions of times higher than the Sun, but it is unclear how they formed. Possibly, many smaller black holes merged. No one can see black holes because they don’t emit light, but astronomers can sense their presence by watching their gravitational influence on nearby stars and detecting the radiation from infalling gas and dust.

[1] Light is moving fast enough to overcome gravity and escape.

[2] Event horizon.

[3] Inside event horizon gravity is so strong that light cannot escape.

[4] On the edge of the event horizon, light is ‘stationary’.

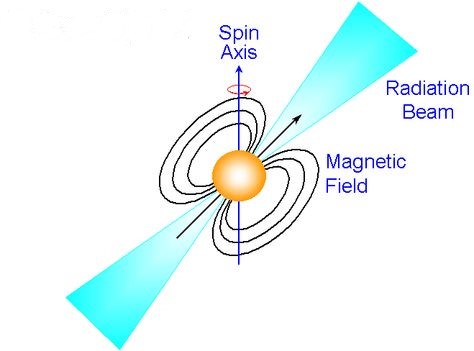

Neutron stars and pulsars

Neutron stars are extremely dense collapsed stars sometimes left behind after a core-collapse supernova explosion. If the collapsing core is 1.4 to 3 times as massive as the Sun, it will form a neutron star, while a heavier core will collapse into a black hole.

Neutron stars form because they are massive enough for their own gravity to compress normal matter into a superdense soup of neutrons surrounded by a solid crust of iron nuclei. Typically, they are about 15 km [9 miles] wide and spin very rapidly, sometimes once every few milliseconds. A teaspoon of material from the core of a neutron star would have a mass of roughly a billion tonnes. Neutron stars also have very intense magnetic fields, which accelerate particles into narrow polar beams emitting bright radiation.

Neutron stars called pulsars are easiest to detect because of their orientation. They happen to be aligned so that they sweep their bright radiation beams across Earth as they spin, so telescopes pick up regular pulses emerging from them.

Structure of a pulsar

[1] Powerful magnetic field around neutron star.

[2] Field channels radiation from star into narrow beams.

[3] Axis of rotation.

[4] Rapid spin of pulsar causes radiation beam to sweep across sky.

Wormholes

A wormhole is a strange, hypothetical tunnel through space–time that could allow someone to take a shortcut from one place to another, apparently faster than the speed of light. No one has found any observational evidence that wormholes really exist, but Einstein’s general relativity theory [see Science Book: Physics] leaves open the possibility that they might.

A wormhole would involve a black hole [see above] connected to a hypothetical ‘white hole’ – an object that would act like the reverse of a black hole, allowing matter to come out, but nothing to get in. Jump into the black hole and you’d pop out again somewhere else in the universe, or even in another universe altogether.

To picture a traversable wormhole, think of a piece of paper bent in half without the two halves touching. A wormhole would be like a tunnel that connected the two sides with a shorter path than that following the curve of the paper, representing ‘normal space’. Whether wormholes could really exist in nature is extremely doubtful, however.

[1] Notice the path of travel through normal space.

[2] The position of the blackhole, the vertical tunnel extending to the base is the wormhole, and the hypothetical ‘white hole’ is at the base of the tunnel.

[3] Above the black hole is the nearby region of space-time.

[4] Below the base of the tunnel or beneath the white hole is the distant region of space-time.

The Big Bang

The Big Bang was a cataclysmic explosion that created our universe around 13.7 billion years ago. The theory’s credibility grew from the 1920s, when astronomers discovered that galaxies are receding from each other on large scales because the cosmos is expanding. That suggests all matter was much closer together in the distant past and points to the origin of the universe in a state of unimaginably high density.

Modern theories suggest that a split second after the Big Bang, a fleeting phase called cosmic inflation made the universe expand exponentially fast. After that, the dense fireball gradually cooled as it expanded more slowly, forming familiar particles such as protons and neutrons, then building atomic nuclei and finally neutral atoms within about 400,000 years. Regions with the highest density eventually collapsed under gravity to form galaxies of stars.

Much of our information about the early universe comes from the microwave background. But it’s still not clear what triggered the Big Bang in the first place.

The expanding universe

[1] Immediately following the Big Bang, cosmic inflation follows.

[2] Before stars begin to form the universe entered a cosmic ‘dark age’.

[3] Temperature falls over time.

[4] Size of observable universe as it is now.

Cosmic microwave background

The cosmic background radiation is the afterglow of the Big Bang. It pervades all space today and has been a vital tool in determining conditions in the early cosmos.

The Big Bang created an expanding fireball of enormous density that effectively trapped photons of light inside it. When the universe was 400,000 years old, however, the fireball had cooled enough for neutral atoms to form. Suddenly, the orange-red glow of heat from the fireball, now at about 3,000 degrees C, could stream freely through the universe in every direction. We still see this radiation today, stretched into invisible microwaves by the universe’s expansion.

The microwave background comes from every direction in the sky, a bit like cosmic wallpaper pasted behind all the galaxies. Satellite measurements reveal that it has subtle ‘ripples’ – tiny variations in wavelength – that arose due to the lumpiness of matter in the early universe. They encode amazingly rich information about the universe’s history, including its age, expansion rate and composition.

Universe

The universe is the totality of all space, matter and energy that exists. It formed in the Big Bang and since then galaxies have evolved within it, forming vast filaments that connect up in a giant cosmic web.

Most of the universe’s mass/energy [73 per cent] is inexplicable dark energy, while 23 per cent is unidentified dark matter. Only about 4 per cent is normal matter, like that found in stars, planets, and people.

Observations suggest the universe is at least 150 billion light-years wide. If the universe is finite, scientists favour the idea that it doesn’t have edges. Instead, space would loop back on itself so that a rocket travelling in a straight line might eventually end up back where it started. Some models suggest the universe might take on one of many endlessly repeating shapes, including one based on a 12-sided dodecahedron.

Alternatively, the universe may be infinite, in which case it has always been infinite, and the Big Bang took place throughout an infinite space.

A finite universe might seem like a hall of mirrors – a rocket travelling in a straight line might encounter the same space over and over again. For instance, a rocket exiting a dodecahedron universe on one face might re-enter on its opposite face.

Gravitational lensing

Gravitational lensing occurs when the gravity of a foreground object bends and magnifies light from an object behind it, an effect predicted by Einstein in his theory of general relativity [see Science Book: Physics].

Dramatic gravitational lensing occurs when the huge gravity of a galaxy cluster magnifies the light of a galaxy behind it. Astronomers can use the effect as a ‘zoom lens’ to detect galaxies so distant that their light has taken more than thirteen billion years to reach the Earth. Occasionally, a galaxy is so well lined-up behind a cluster that the lensing effect distorts it into a neat circle called an Einstein ring.

On a smaller scale, a similar effect called microlensing can reveal new extrasolar planets [see above]. When one star passes in front of another, the front star’s precise distortion of the background one can carry subtle clues that a planet is orbiting the front star. Bizarrely, this allows astronomers to detect invisible planets circling invisible stars – the technique can work even if the front ‘lensing’ star is too faint to see.

Lensing from galaxy clusters

Observe the following:

[1] A distant galaxy

[2] An intervening galaxy cluster

[3] An observer on Earth

[4] How the cluster’s gravity bends the path of light from the distant galaxy

[5] How the distorted light creates rings and arcs

Dark matter

Dark matter is a mysterious invisible substance that makes up around 85 per cent of all the matter in the universe. Scientists know it is there only because it exerts a powerful gravitational force on visible stars and galaxies, influencing the way they move.

Since the 1930s, evidence has grown that stars in many galaxies move so fast that the galaxies should fly apart, unless they are held together by the gravity of dark, invisible matter. No telescope can see this dark matter. Unlike the normal atoms in stars, planets, or people, it must be profoundly invisible and incapable of emitting or reflecting light. Dark matter may consist of ‘weakly interacting massive particles’, or WIMPS, that congregate into vast balls in and around galaxies.

An alternative explanation for this puzzle is ‘modified Newtonian dynamics’ [MOND], which assumes gravity’s strength changes on large scales so dark matter is not needed to explain star and galaxy motions. But no one-size-fits-all MOND theory so far explains all astronomical observations simultaneously.

Galaxies of bright stars sit inside vast balls of invisible dark matter that scientists have not yet identified.

Dark energy

Dark energy is a strange, unexplained effect that is causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate. Measurements suggest it’s the dominant ingredient of the universe, accounting for 73 per cent of its total energy density.

The universe has expanded since the Big Bang, and until the mid-1990s, astronomers assumed this expansion was gradually slowing down due to the attractive gravitational pull of all the matter inside, which resists expansion. But since then, studies of distant Type la supernovae [see above] have shown that they are dimmer than expected because the expansion of the universe has accelerated over time.

In other words, the universe contains ‘dark energy’ that is pushing galaxies apart. It might arise from a ‘cosmological constant,’ a vacuum property that makes space ‘springy’. Alternatively, space might be filled with an exotic ‘quintessence’, which acts as if it has a negative gravitational mass and hence causes repulsion. NASA and the European Space Agency continue to plan spacecraft missions to study dark energy further.

Ingredients of the universe

Ordinary atoms in galaxies = 0.4 per cent

Ordinary atoms in intergalactic gas = 3.6 per cent

Dark matter = 23 per cent

Dark energy = 73 per cent

SPACEFLIGHT

This is a brief section that will focus on rocketry, satellites, and planetary probes. These issues are important aspects to understand within astronomy.

Rocketry

Rocketry is the technology that enabled all the feats of the space age, including satellite launches, planetary probes, and astronauts landing on the Moon. All rockets work by the principle of action and reaction in Newton’s third law of motion [see Science Book: Physics] – they push forwards by ejecting propellant backwards extremely fast. Most liquids burn liquid or solid fuel to achieve this.

The Second World War and the Cold War were driving forces for military rocket development and the subsequent space race that followed. The German V-2 rocket, developed as a ballistic missile, is often considered the first object to have reached space on a suborbital flight, while a Soviet rocket launched the first satellite, Sputnik 1, in 1957. Human spaceflight began in 1961.

A rocket has to attain a specific speed, the so-called escape velocity, to overcome Earth’s gravity and travel beyond our planet. From Earth’s surface, the necessary escape velocity is about 11.2 km/s [25,000 mph] – roughly ten times faster than the record speed for a jet aircraft.

Escape velocity allows a projectile to overcome Earth’s gravity

Note that a projectile would not only need enough power to enter orbit but also to escape gravity altogether on existing.

In the formula given to calculate escape velocity, R = radius of the Earth.

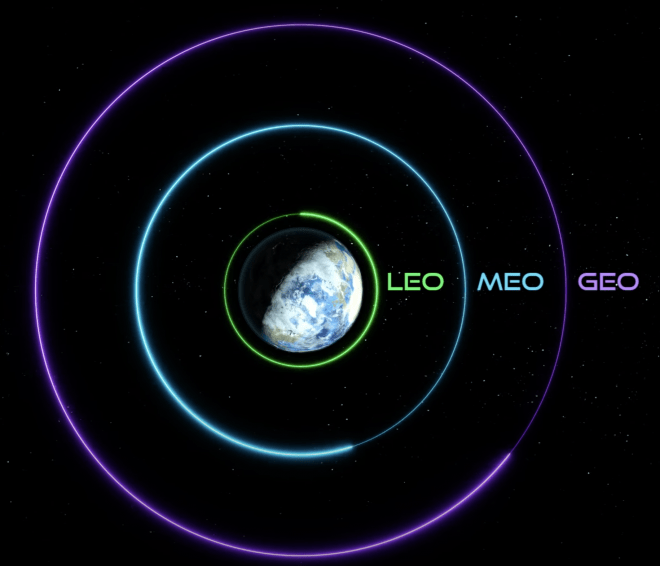

Satellites

Artificial satellites are spacecraft in Earth orbit [or probes orbiting another planet or the Moon]. Today, there are at least 900 operational Earth satellites for purposes such as communications, navigation, or weather forecasting.

Satellites are placed into orbit with a fixed speed – not so fast that they escape the Earth’s gravitational pull, and not so slow that they fall back down to Earth. Many satellites, such as military reconnaissance satellites, are placed in low Earth orbits to get a close-up view of the Earth’s surface.

Most communications satellites orbit in the ‘geostationary ring’ about 35,786 km [22,236 miles] above the Earth’s equator. At this altitude, an orbit takes 24 hours, so a satellite hovers over a fixed point on the ground as the Earth rotates, maintaining a fixed communications link.

More than 5,000 tonnes of technology circles above our heads today. But most of it is useless ‘space junk’, such as discarded rocket stages, which threatens to damage operational satellites through collisions.

Planetary probes

Interplanetary spacecraft missions began in earnest in 1959, when the Soviet Union successfully crashed a probe, Luna 2, into the Moon. The Soviet Venera 7 probe was the first to beam back data from another planet after landing on Venus in 1970, while NASA’s Mariner 9 spacecraft became the first to orbit another planet, arriving at Mars in 1971.

Several missions have robotically gathered extraterrestrial samples and returned them to Earth for analysis. Between 1970 and 1976, three Soviet missions returned samples of lunar soil. Other sample-return missions include NASA’s Stardust project, which returned dust samples from a comet in 2006, and the Japanese Hayabusa mission, which returned asteroid samples in 2010.

Most of the attempted missions to Mars in the late 20th century flopped, but success rates over the last decade and a half have dramatically improved. NASA’s robotic rovers Spirit and Opportunity, for instance, operated on Mars for more than six years – more than 20 times longer than expected.

This completes Science Book (Astronomy). Amendments to the above entries may be made in future.