– ‘Science Book: Biology’ seeks to address all of the fundamental concepts within biology. This is Book 3 in the science series. ‘Science Book: Physics’ and ‘Science Book: Chemistry’ can be found on separate pages on this site by clicking on the link in the main header section

Proteins. Proteins are large, complex molecules that play may critical roles in the cells of the body. They consist of long chains of hundreds or thousands of smaller simple molecules called amino acids. Some of these are “essential amino acids”, such as phenylalanine, which our bodies don’t synthesise, so it’s essential that we eat plenty of these in our diet.

Some proteins act as antibodies, which can prevent disease by targeting foreign particles such as viruses and blocking the sites they use to invade cells. Others include receptors and enzymes, which enable thousands of chemical reactions to take place in cells and assist the construction of new proteins by reading the genetic information in DNA.

In plants and animals, all proteins are made from different sequences of 20 main amino acids. The exact sequence for a given protein is called its primary structure. When a cell makes a new protein, it forms a linear chain of amino acids that coils into a secondary structure before morphing into a final three-dimensional shape through a process called protein folding.

Carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are organic compounds made of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen atoms. In food science and informal contexts, the term “carbohydrate” often just means any sugary food like chocolate or a starchy food such as bread or pasta.

The most basic carbohydrates are simple sugars or “monosaccharides” such as fructose [C6H12O6], which makes fruit sweet, or ribose [C5H10O5], which forms the backbone of the genetic molecule RNA. Monosaccharides, especially glucose, are also the major source of fuel for metabolism. Glucose has the same chemical formula as fructose but a different, typically ring-shaped molecular structure.

The larger “disaccharide” sucrose [C12H22O11] – common table sugar – is formed from fructose and glucose. The most complicated carbohydrates are “polysaccharides”, including starch, which is made up of thousands of glucose units. Plants store their glucose fuel as starch. Many animals, including humans, store glucose as glycogen, a molecule containing a core protein surrounded by many branching glucose units.

Lipids. Lipids are a broad family of molecules including fats, waxes and some vitamins [including vitamins A, D, E and K] that are “hydrophobic” – they repel water and are only soluble in organic solvents such as acetone. Lipids have a wide range of biological functions, including storing energy, maintaining cell membranes and acting as hormones that are able to coordinate complicated processes like fertility.

Common lipid types include fats, steroids and phospholipids. Fats store energy and cushion organs, protecting them from damage, and are composed of fatty acids and glycerol, a sweet-tasting alcohol. Steroids contain four ring-shaped hydrocarbon molecules and include the dietary fat cholesterol as well as the sex hormones estradiol and testosterone.

Phospholipids usually contain two fatty acids and a phosphate group. In water, they arrange themselves into a two-layered sheet with all their hydrophobic tails lined up in the middle. This layered structure forms cell membranes, which regulate the flow of ions and molecules in and out of a cell.

Metabolism. Metabolism describes the host of chemical reactions required to keep living organisms alive, generating energy for essential growth and reproduction – for instance, healing injuries and eliminating toxins.

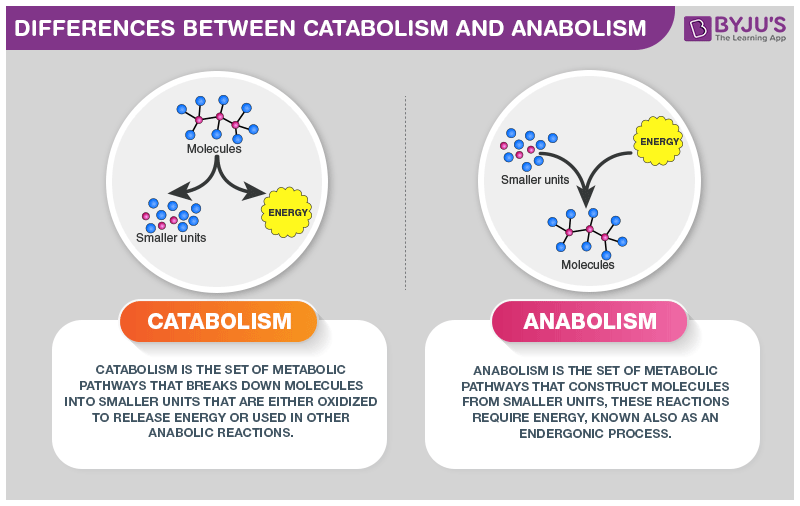

Apart from water, most molecules in living organisms are amino acids, the building blocks of protein, as well as carbohydrates and lipids. Metabolic reactions involving them divide into two categories. “Anabolism” builds molecules like proteins during construction of new cells and tissues, while “catabolism” breaks down molecules from food for use as a source of energy.

Enzymes also play a vital role in metabolism by acting as catalysts that efficiently transform one chemical into another, helping amino acids join up to form proteins, for instance, or breaking down dietary starch into its component sugars. Healthy metabolism in humans depends on good nutrition, plentiful water and exercise. A lack of any one of these decreases your metabolic rate and can lead to weight gain.

Chemosynthesis. Chemosynthesis is the process by which some exotic microbes living in hot deep-sea vents derive their energy. It’s similar to photosynthesis, but doesn’t use sunlight. Instead, the energy comes from the oxidation of inorganic chemicals such as hydrogen sulphide bubbling up from the Earth’s crust.

In hydrothermal vents, geothermal heat coming up from fissures on the ocean floor can heat water to more than 100°C. Amazingly, some bacteria called extremophiles thrive in these vents at temperatures up to about 120°C. There’s no sunlight available, so the bacteria produce their energy by turning available chemicals into sugar. For instance, some bacteria oxidise hydrogen sulphide and use the energy stored in its chemical bonds to make glucose from water and caron dioxide dissolved in sea water.

Scientists speculate that these bacteria would have been well adapted to the hot conditions on the early Earth, making them a good candidate for one of the earliest types of life.

Receptors. In biochemistry, a receptor is a protein molecule in the membrane or cytoplasm of a cell, onto which signalling molecules such as hormones attach to deliver chemical instructions. For example, the hormone insulin regulates blood sugar by latching onto a receptor in muscle or liver cells, triggering reactions that speed up sugar absorption.

Signalling molecules effectively target specific receptors because they have the right size, shape and electric charge distribution to grab hold of them, a bit like a key fitting into a lock. The binding “unlocks” the cell to cause chemical changes. Many drugs mimic signalling molecules to promote their effect. For instance, morphine mimics endorphins, naturally occurring feel-good chemicals in the body that relieve pain.

Other drugs lock onto receptors purely in order to block up available binding sites, inhibiting the effects of natural signalling molecules. Examples include antihistamines, which alleviate allergies by inhibiting chemicals called histamines that causes rashes, sneezing and itching.

The surface of a body cell is covered in specific receptor sites, to which only certain natural body chemicals or drugs will fit. Once attached, these chemicals trigger specific actions within the cell.

DNA. Deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, is the molecule that encodes the genetic instructions for the development and function of all living, self-replicating organisms. Nearly every cell in a person’s body has the same DNA, which is mostly inside the cell nucleus, although some of it resides in mitochondria.

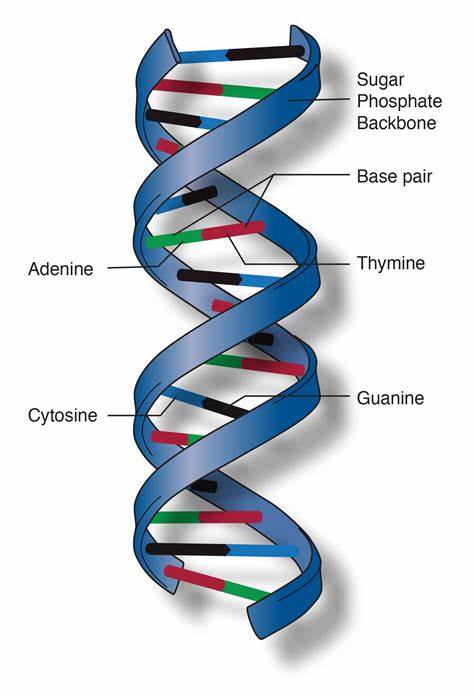

The information in DNA is stored as a sequence of four chemical “bases” called adenine [A], guanine [G], cytosine [C] and thymine [T]. The bases team up [A with T, C with G] to form units called base pairs. Human DNA consists of about 3.2 billion base pairs. Each base is attached to a sugar molecule called deoxyribose and a phosphate molecule to form a “nucleotide”.

The nucleotides are arranged in two long strands that form a double helix shaped like a spiralling ladder, with the base pairs forming the rungs and the sugar and phosphate molecules forming the vertical supports. DNA replicates itself by splitting into single strands that serve as templates for duplicating the sequence of bases.

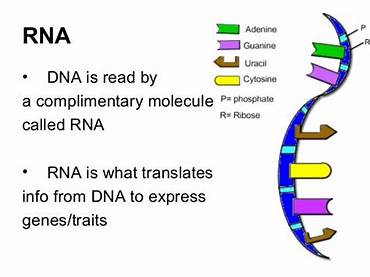

RNA. Ribonucleic acid or RNA is a molecule that has some similarities to DNA but does not store genetic information (except in RNA viruses). Instead, RNA performs many different functions in a cell, acting as a temporary copy of genetic information, for instance.

Like DNA, RNA molecules have a sequence of four chemical “bases”, in this case uracil [U], adenine [A], cytosine [C] and guanine [G]. Each base is also attached to a sugar molecule [ribose] and a phosphate molecule to form a “nucleotide”. The bases sometimes team up with each other [U with A, C with G] to form a double helix structure like DNA, but RNA usually occurs as a single strand.

“Messenger” RNA [mRNA] is a short-lived molecule that copies a cell’s DNA and carries it to the cell’s protein synthesis machinery, the ribosome, which reads off its information to make the right protein. “Transfer” RNA [tRNA] molecules latch onto individual amino acids and frogmarch them to the ribosome, where they are incorporated into proteins.

Genes. Genes are segments of DNA that act as a blueprint for the production of specific proteins. They exist in alternative forms called alleles, which determine the distinct traits that parents pass on to their offspring according to the laws of inheritance. The entirety of an organism’s genetic information is called the genome.

The 13-year Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, was a mammoth international effort to identify the sequences of the 3.2 billion base pairs in human DNA and to identify its approximate 25,000 genes. This showed that the average gene consists of about 3,000 base pairs, but sizes vary enormously, with the largest gene having 2.4 million base pairs.

The Human Genome Project has clarified the role that certain gene sequences play in certain diseases (such as muscular dystrophy and certain cancers). However, it also revealed that only about 2 per cent of the genome actually encodes instructions for protein synthesis, and that the role of some of the remaining DNA remains a mystery.

Chromosomes are threadlike structures of nucleic acids and protein which are found in the nucleus of most living cells. They carry genetic information in the form of genes.

Laws of inheritance. The laws of inheritance and heredity are basic rules about how animals and plants pass on traits to their offspring. Gregor Mendel, a 19th-century Austrian monk, discovered the laws in pea-breeding experiments, in which he cross-fertilised pea plants and studied traits like flower colour and the length of plant stems in subsequent generations.

Mendel’s experiments revealed that two factors (now known to be genes) determined the traits, one from each parent, and if the two inherited factors are different, the offspring expresses just one of them, the so-called “dominant” trait. He also noticed that different traits like flower colour and stem length are inherited independently.

Today, we know that all the human blood groups (A, AB, B or O) are determined by a single gene. A and B are dominant while O is “recessive”, so a child who inherits A + O or B + O from its parents will have blood types A and B respectively. A and B are said to be “co-dominant”, so that inheriting both A and B gives blood type AB.

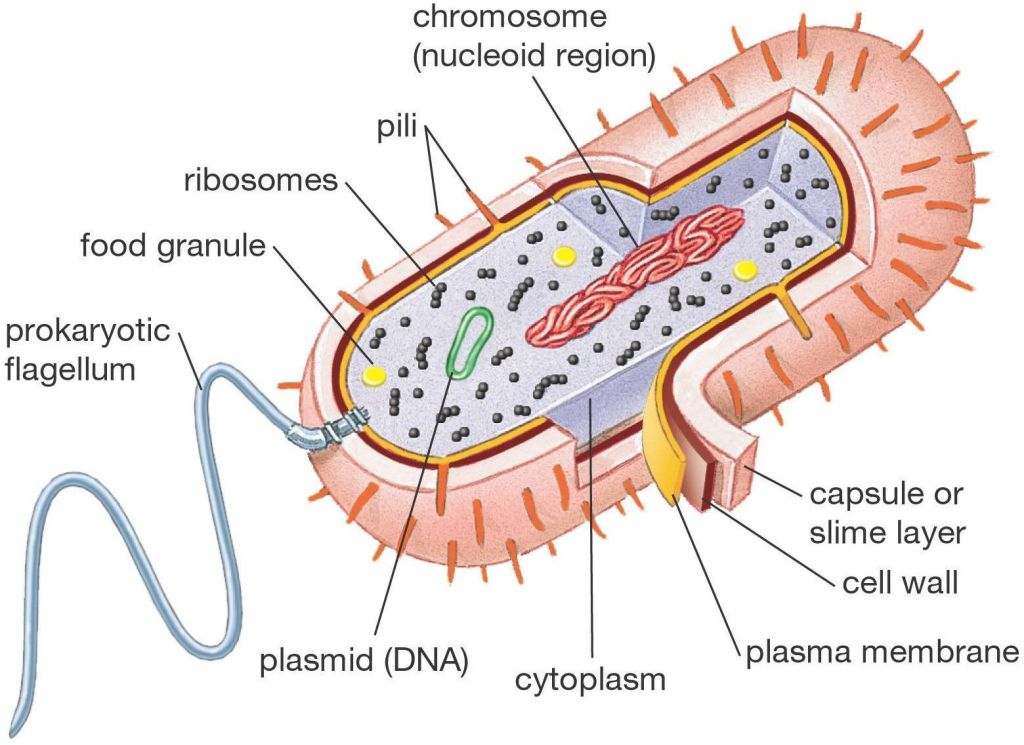

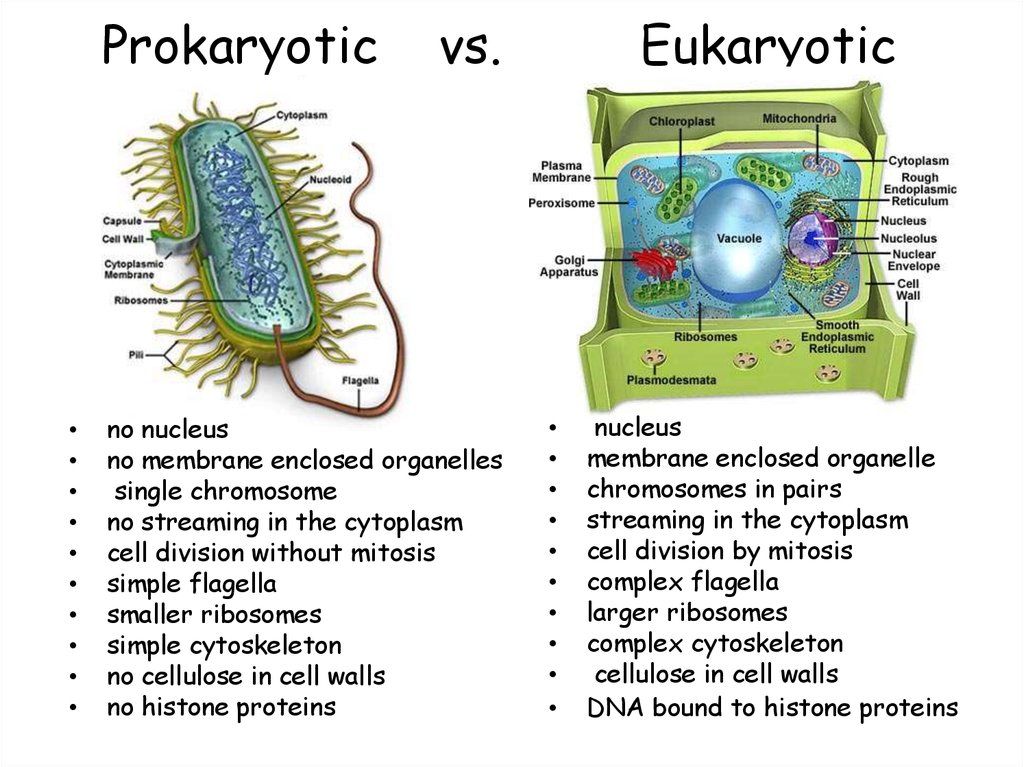

Prokaryotes. Prokaryotes are simple single-celled organisms that don’t have a cell nucleus that houses DNA. Instead, their DNA forms a free-floating bundle in the middle of the cell. Like eukaryotic cells, prokaryotes have ribosomes where amino acids are assembled into proteins and sometimes a “flagellum” – a rudder-like tail that propels them.

The fossil record reveals that prokaryotes evolved on Earth very early, at least 3.5 billion years ago. They reproduce asexually and are typically about 1-10 micrometres [millionths of a metre] wide. They fall into two subcategories: bacteria and archaea.

Bacteria were discovered in the late 1600s and are ubiquitous in every habitat on Earth. They have a wide range of shapes, including spheres, spirals and rods. Archaea were first classified as a separate group in the late 1970s. Most look similar to bacteria but they have a completely different genetic and biochemical make-up, and often inhabit extreme habitats such as scorching hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor.

Eukaryotes. Along with prokaryotes, eukaryotes are one of the two major cell types – they make up everything from single-celled amoebas to complex animals and plants. A typical size for a eukaryotic cell is roughly 0.01 mm across – about 10 or 15 times wider than a typical prokaryote.

The ”plasma membrane” forms the outer barrier of a eukaryotic cell, while the cell nucleus houses DNA packaged into chromosomes that vary widely between organisms. Humans have 23 pairs of large, linear chromosomes.

The nucleus is surrounded by a water-rich fluid called cytosol and various organelles that perform different tasks. Mitochondria, for instance, generate energy, while the endoplasmic reticulum is a network of interconnected membranes dotted with ribosomes, which assemble proteins.

Fossil evidence suggests eukaryotes evolved at least 1.7 billion years ago. One possibility is that they arose because some prokaryotic cells engulfed others, which were not digested but lived on as organelles and reproduced.

Mitochondria. Mitochondria acts as the power sources of eukaryotic cells, converting the energy from food into a form that cells can use. A cell may have hundreds or even thousands of mitochondria depending on its energy demands.

Mitochondria are like little factories that specialise in using energy from reactions between oxygen and simple sugars to produce molecules of adenosine triphosphate [ATP], the cell’s main energy source. ATP is a bit like a charged battery – removal of a phosphate group releases energy to drive complex reactions, leaving “uncharged” adenosine diphosphate [ADP], which returns to mitochondria to be recharged into ATP.

Surrounded by two membranes, mitochondria have their own genetic material and reproduce independently of their host cell. Scientists suspect that the ancient ancestors of mitochondria were probably free-living bacteria that somehow became engulfed in other cells. The bacteria thrived in the protective environment of their new host cells, while the hosts came to rely on the bacteria for energy production.

Ribosomes. In all cells, including those of plants, animals and bacteria, ribosomes are the mini factories that assemble proteins. Each ribosome is built from RNA molecules and proteins. Some of them are free to roam in the watery cytoplasm of a cell, while others are bound to the endoplasmic reticulum, a complicated network of interconnected membranes inside eukaryotic cells.

A strand of messenger RNA [mRNA] brings a copy of genetic information from a cell’s DNA to a ribosome. Meanwhile, transfer RNA [tRNA] molecules latch onto single amino acids and deliver them to the ribosome, to be incorporated into proteins according to the mRNA’s instructions.

Cells typically have several thousand ribosomes, but the number can reach several million. The chemical structure of ribosomes is different in bacteria and animal cells, and the differences allow many antibiotic drugs to selectively disrupt the ribosomes of disease-causing bacteria, sabotaging their protein production without making people or animals sick.

Cell division. Cell division is the process by which biological cells multiply. Eukaryotic cells, including human cells, create identical copies of themselves for growth or repair of tissues through a process called mitosis. The double-stranded DNA in the cell nucleus unzips into two strands that each join with nucleotides to form two copies of the original DNA. In the next step, “cytokinesis”, the cell splits into two identical copies of the original cell.

“Meiosis” is a type of cell division that creates eggs and sperm for sexual reproduction. The eggs and sperm cells have half the normal number of chromosomes. When sperm fertilisers an egg, they fuse to regain the normal chromosome quota, half from the male and half from the female.

Prokaryotic cells such as bacteria usually divide in a process called binary fission. The single DNA bundle in a prokaryotic cell replicate, then the two copies stick to different parts of the cell membrane, going their separate ways when the cell splits into two.

Gametes. Gametes are the germ cells of animals and plants that reproduce sexually. In most animals, including humans, the male gametes are called sperm cells and the female ones are called eggs (ovum).

Gametes form in a cell division process called meiosis, in which a cell splits into four copies instead of the usual two, so that the gametes contain half the normal number of chromosomes – just one of each of the 23 pairs normally found in human cells. “Chromosomal crossover” occurs during meiosis, each chromosome pair exchanging genetic material so that the gametes end up with new combinations of genes.

During fertilisation, an egg and sperm fuse to create a “zygote” with two copies of each chromosome, one from the male and one from the female. This single cell develops into an embryo by cell division. In most mammals, the X and Y sex chromosomes determine gender. Inheriting an X chromosome from both parents gives female offspring [XX], while inheriting X from the mother and Y from the father gives males [XY].

In essence, one chromosome from each parent. Chromosomes exchange genetic material during meiosis and the inherited chromosomes have a new combination of genes which determines gender and offspring characteristics.

Biological classification. The basic classification system for animals, plants and microbes was first introduced in the early 1700s by the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus, who grouped species according to shared physical characteristics. The groupings have been revised since then to take account of new information about evolutionary trees.

Today many scientists divide all life into three domains: Archaea and Bacteria and Eukaryota, which includes complex animals and plants. The domains are subdivided into kingdoms, usually six: Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista, Archaea, Bacteria. Subcategories of the kingdoms multiply into phyla, classes, orders, families and genera with the final, most specific category being species.

Typically, a species is a group of organisms that are biologically similar enough to each other that they can interbreed to create fertile offspring. The number of species of life on Earth is impossible to measure – scientists guess that it lies anywhere between about 5 million and 100 million.

Animals. Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms from the kingdom Animalia, and they form a vast group of more than 1.5 million known species including worms, insects, sponges and people. All animals are “heterotrophs” – unable to generate some vital organic chemicals internally, and so must eat other organisms to stay alive. As they develop, their body plans become fixed, although some animals undergo metamorphosis – for instance, when a caterpillar pupates and transforms into a butterfly.

Some animals reproduce asexually, including aphids, which sometimes reproduce independently by effectively cloning themselves. But the vast majority of animals reproduce by sexual reproduction, in which a male and female combine their genetic material to create their offspring.

Animals usually sexually reproduce when an egg and sperm fuse during fertilisation to create a “zygote” with two copies of each chromosome, one from the female and one from the male. This zygote develops into an embryo by cell division.

Plants. Plants are multicellular eukaryotic organisms that use sunlight to generate energy and organic chemicals through photosynthesis. They include familiar organisms like grasses, bushes and trees as well as green algae, which are largely aquatic and exist as single cells, colonies and seaweeds. There are approximately 350,000 known species of plants.

Plants typically have a main stem growing up from a root system in soil, with branches emerging from “nodes” on the stem. Sexual reproduction in plants often involves male pollen grains fertilising the ovules in a flower. Protective seed coats form around the fertilised ovules before they disperse, allowing a new generation of plants to germinate. Asexual reproduction doesn’t involve flowers – plants can create genetically identical copies of themselves when bulbs divide, for instance.

The first land plants evolved more than 450 million years ago, while forests spread on land around 385 million years ago. Flowering plants evolved roughly 140 million years ago, and since then have become the dominant land plants.

. Roots draw water and nutrients from soil in a process called osmosis

. The stem transports material around the plant in a chemical process known as active transport

. Leaves are the main centres of photosynthesis, a chemical process which uses energy from the sun

. The flower carries organs for sexual reproduction – stamens and/or ovaries

Photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is the process in which plants, as well as some bacteria and eukaryotic microorganisms, use the energy from sunlight to produce sugars like glucose. Plant leaves are like solar energy collectors crammed full of photosynthetic cells. These cells combine water and carbon dioxide molecules to create sugars and oxygen.

Water enters a land plant through its roots and is then transported up to the leaves. Atmospheric carbon dioxide enters the leaves through tiny pores called stomata, which open and close depending on environmental conditions. Likewise, oxygen produced during photosynthesis passes back out into the atmosphere through the stomata.

During respiration – the reverse of photosynthesis – plants combine sugar with oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and water, and in the process creates adenosine triphosphate, or ATP [see above], the molecule that supplies energy for essential work like protein building. Plant respiration dominates at night, when the photosynthetic uptake of carbon dioxide and release of oxygen stops.

Prokaryotic microbes. Microbes made of prokaryotic cells [see above] fall into two classes: bacteria and archaea, which are both single-celled. These microbes are the most diverse and abundant group of organisms on Earth, accounting for at least half of all biomass, despite their tiny size [they are typically about one-thousandth of a millimetre wide].

Bacterial cells come in a wide variety of shapes. Spherical ones are called cocci, while elongated rod-shaped ones are called bacilli. Sometimes, bacteria come in pairs, where their name is prefixed with ‘diplo-’. Those that form long chains are prefixed ‘strepto-’, while some bacteria form triangular groups prefixed ‘staphylo-’. Rod-shaped bacteria can divide to form a picket-fence structure called a palisade arrangement.

Many bacteria cause diseases. Streptococcus species can cause pneumonia and meningitis, for instance. Archaea look similar to bacteria but have a completely different biochemical make-up and do not have a known role in disease. Archaea were possibly the earliest life forms on Earth.

Eukaryotic microbes. Eukaryotic microbes are a diverse range of organisms so small that they are invisible to the naked eye. They divide into four groups: animals, plants, fungi and “protists”. Unlike the simpler prokaryotic microbes, the bacteria and archaea, eukaryotic microbes house their DNA inside a cell nucleus.

Micro-animals include dust mites and many nematodes [roundworms] as well as rotifers, tiny filter feeders usually found in fresh water. Some microscopic, photosynthetic green algae are classed as plants. Fungi have several single-cell species, including baker’s yeast. Protists are a diverse group of organisms that have little in common except simplicity – they are single-celled or multicellular without specialised tissues.

Like bacteria, eukaryotic microbes can cause serious diseases, including malaria, while some fungi present a major health hazard to crops. Finding treatment for these diseases is challenging because any chemical that kills eukaryotic organisms or inhibits their growth is also likely to be toxic to the eukaryotic cells of plants or animals.

Important eukaryotic microbes include those that cause sleeping sickness [Trypanosoma gambiense] and amoebic dysentery [Entamoeba histolytica].

Viruses. Viruses are tiny packets of genetic material capable of infecting the cells of living organisms, including animals, plants and bacteria. Viruses can’t reproduce on their own. Instead, they breed by invading the cells of a host and hijacking their replication machinery.

Viruses consist of RNA or DNA protected by a protein coating and are typically only 10-300 nanometres [billionths of a metre] in size. They infect organisms by penetrating cell membranes, releasing their genetic cargo and forcing the doomed cells to replicate them. New viruses assemble inside each host cell before bursting out, killing the cell. However, some viruses can remain dormant inside cells for years.

Plant viruses are often transmitted between plants by insects that feed on them. Human colds and flu spread through coughing and sneezing, while several viruses are transmitted by sexual contact, including the human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]. Fortunately, our immune systems successfully combat most viral infections, while vaccinations can prevent others.

Origins of biochemicals. Scientists can only speculate on how the organic compounds necessary for life emerged on Earth. They could have arisen spontaneously from chemical reactions of simpler compounds, or they could have arrived from space.

A famous experiment at the University of Chicago in 1953 tested whether stormy conditions on the young planet could have triggered reactions between simple chemicals to create the ingredients of life. Stanley Miller and Harold Urey zapped a mixture of water, methane, hydrogen and ammonia with electrical discharges to simulate lighting. This cooked up many organic compounds including amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

Since then, evidence has emerged that vigorous volcanism on the early Earth enriched the chemical soup with carbon dioxide, nitrogen and sulphur compounds. These could have spurred the production of biochemicals. And astronomers have identified organic molecules including amino acids in comets. Comet impacts could have delivered off-the-shelf biochemicals.

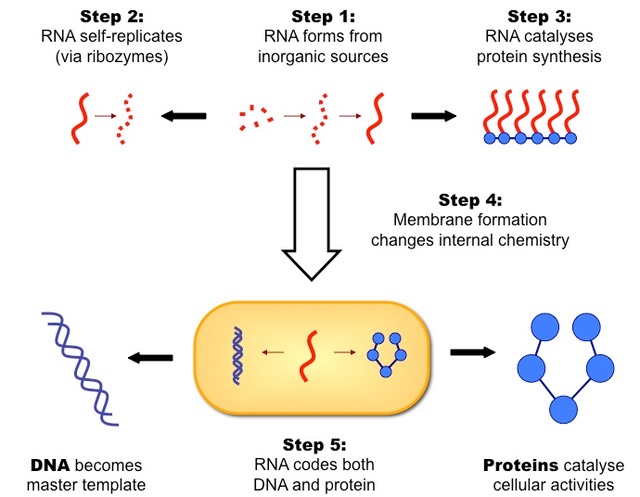

Replicating life. The early Earth somehow acquired the complex organic chemicals necessary for life. But how did the jump from inanimate chemicals to living, self-replicating organisms occur?

One puzzle about life’s origins is that all self-replicating organisms today use DNA to store the genetic information needed to build proteins, while protein enzymes are necessary to copy the DNA and spawn new generations. In other words, DNA and proteins are both vital to life, but the chances that the Earth cooked them up simultaneously seem remote and slim.

An alternative idea is the “RNA world” hypothesis, which proposes that the earliest replicating organisms depended solely on RNA [see above], which is better at multitasking than DNA – it can act as an enzyme as well as a carrier of genetic codes. However, many scientists are unconvinced that complex RNA molecules could have spontaneously assembled in early-Earth conditions. Ultimately, it may be impossible to find a convincing theory for how life arose unless a simple “one-pot” experiment repeats it in a very compelling way.

Extra-terrestrial origins of life. There’s one intriguing alternative solution to the mystery of how life arose on Earth – it didn’t. A theory called panspermia suggests that comets and meteors from space not only delivered complex organic chemicals to the young Earth, they also delivered bona fide living organisms from which all life evolved. In that case, we are all descended from aliens.

Proponents of panspermia suggest that simple life is widespread on bodies like comets throughout the solar system, and possibly beyond. Comets that hit Earth, delivering much of the water in its oceans, could also have brought fully functional living microbes that had gradually evolved in space over billions of years. That would explain why life “emerged” on Earth so astonishingly quickly after our planet became inhabitable.

What’s more, there is intriguing evidence that some hardy bacteria can survive the harsh conditions of space, and even a violent impact on a planetary surface. But panspermia remains highly speculative – although there are hints that bugs could exist in space, there is no direct evidence that they actually do.

Evolution. Evolution describes the way populations of living organisms change over time due to changes in heritable genetic traits, such as eye colour in humans. Sometimes the changes are due to environmental pressures – for instance, giraffes may have evolved long necks because those eating plentiful foliage high in the trees survived to produce most offspring.

This “natural selection” is one key driver of evolution, but other genetic factors come into play. Spontaneous, random mutations of genes can sometimes create a beneficial trait that helps an organism produce more offspring, so the mutation persists in the population. “Genetic drift” also plays a role – certain gene variants might flourish simply by chance.

Sometimes two or more species can evolve through co-evolution, when they have close ecological interactions with each other. For instance, a plant might evolve thorns to deter herbivores, while the herbivores in turn evolve defences against thorns that thwart the plant’s strategy.

Natural selection. Natural selection is one of the basic mechanisms of evolution. The British scientists Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed the theory in 1858.

Organisms have different traits, such as size, and these influence whether or not an organism survives long enough to pass on their traits to their offspring. Advantageous traits become more common in successive generations. Over time, populations split into different species [“speciation”], and looking back in time, any pair of organisms shares a common ancestor. For instance, humans shared a common ancestor with chimpanzees about 6 million years ago.

Peppered moths offer an example of rapid natural selection during the industrialisation of the United Kingdom. Common pale-coloured peppered moths became conspicuous on tree trunks that had darkened with soot, making them easy prey for birds, while darker ones preferentially survived long enough to breed. Eventually, the population became primarily dark, but the process reversed when the clean air standards were enforced.

Genetic drift. Genetic drift is one of the driving forces behind evolution. It describes the way that certain traits in a population might flourish or vanish by chance, because individuals with these traits happen to breed most offspring or no breed at all.

Genetic drift tends to rapidly reduce genetic diversity in very small populations. For instance, if only two individuals in a population of ten animals carry a certain gene variant, and do not breed fertile offspring, that variant will be gone from the population for good.

A special case of genetic drift is the “founder effect”, which occurs when a small number of individuals become isolated from the main population. For example, in the late 1700s, a typhoon on the island of Pingelap in Micronesia left only 20 human survivors to create future generations. Today, 5–10 per cent of the island’s population suffer from a total colour blindness disorder that is extremely rare elsewhere, because one of the typhoon survivors must have carried a recessive gene linked to the disorder.

Human origins. All living people today are descended from a single female dubbed “mitochondrial Eve” who lived in Africa about 110,000 –130,000 years ago. Scientists deduced this from modern genetic analysis of the DNA in human mitochondria, which is inherited via the maternal line.

The widely accepted “Out of Africa” theory suggests that modern humans [Homo sapiens] first evolved in Africa roughly 200,000 years ago, then migrated out all over the world during the last 100,000 years. They reached the Middle East by about 70,000 years ago, south Asia by 60,000 years ago and western Europe around 40,000 years ago. The dates for North American colonisation are unclear – this may have started around 30,000 years ago or much later.

These human settlers largely replaced indigenous pre-human species, such as the heavy-browed Homo erectus in Asia. However, genetic evidence hints that some interbreeding took place between anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals, members of the genus Homo that died out 30,000 years ago.

This completes Science Book (Biology). Amendments to the above entries may be made in future.