– ‘Science Book: Earth Science’ seeks to address all of the fundamental concepts within the field of Earth Science. This is Book 4 in the science series on this site.

Earth history. The Earth formed around 4.56 billion years ago, when matter gradually clumped together in a swirling disc of gas and dust around the Sun. The young Earth was hot enough for heavy metals inside to melt and sink into the planet’s core, creating a separate core and mantle. About 4.53 billion years ago, a Mars-sized body is thought to have crashed and collided into the Earth, creating the Moon.

The history of the Earth is divided into four eons, starting with the Hadean, which lasted until 3.8 billion years ago. Towards the end of the Hadean, Earth was pummelled by meteorites during the “late heavy bombardment”. Water-bearing comets also pelted the Earth’s surface, delivering water to form oceans.

Life arose on Earth soon after the late heavy bombardment, and photosynthesis by primitive plants began enriching the atmosphere with oxygen around 3 billion years ago. During the current Phanerozoic eon, covering the last 542 million years, the continents gradually merged into a single landmass called Pangaea, then later split to form the familiar continents today.

Pangaea is Greek for “entire Earth”. Around 250 million years ago, all Earth’s continents were joined together as one giant landmass – including North America, South America, Eurasia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica and India – forming the Pangaea.

Earth’s structure. The outermost layer of the Earth is the crust, which consists of the continents and the ocean floors. Continental crust is typically about 35–70 km thick. The silicate rocks granite and basalt are the most common rocks in the Earth’s crust.

The next layer is the mantle, composed mainly of hot, mushy silicates. It is about 2,900 km thick. Large convective cells in the mantle circulate heat and drive plate tectonics. The Earth has a fluid, iron-rich outer core and a solid inner core, which is probably mostly made of iron with some nickel.

The temperature inside the Earth is thought to rise about 25–30°C for each kilometre of depth. Some of that heat is left over from the planet’s formation, but most comes from the radioactive decay of unstable elements. Scientists deduce the Earth’s deep internal structure by measuring how seismic waves from earthquakes propagate through it.

Geomagnetism. Geomagnetism refers to the Earth’s magnetic field, which is similar to that of a bar magnet. The magnetic north and south poles are close to the geographic poles, but the magnetic poles wander by up to about 40 km each year. The northern and southern lights [“aurorae”] are eerie glows that occur near the magnetic poles when energetic particles from the Sun excite atmospheric molecules.

The dynamo theory suggests that Earth’s magnetic field sustains itself via a feedback mechanism. The field induces electric currents in the metallic liquid outer core, while convection currents and the Earth’s rotation organise these currents into spirals aligned from north to south. These currents induce a magnetic field that reinforces the original field, creating a self-sustaining dynamo.

Magnetic fields preserved in ancient lava flows show that the Earth’s magnetic field flips over every few hundred thousand years or so, with the north pole moving to the south pole, and vice versa. There is no consensus on why this happens.

. More on the science and general principles of magnetism can be found in Science Book: Physics

Earth’s shape. The Earth’s shape is a flattened sphere because it bulges out at the equator slightly due to its rotation. Its average diameter is 12,742 km [7,918 miles], but the polar diameter is about 0.3 per cent less than the equatorial diameter.

The coordinate system for the Earth’s surface uses lines of latitude and longitude. Longitude lines run from north to south, while latitude lines form circles that get smaller towards the poles. By convention, the “prime meridian” that passes through Greenwich in London marks zero longitude, while zero latitude falls on the equator. The positions of any point on Earth’s surface can then be described in degrees north or south and east or west. New York, for instance, is at 41° North, 73° West.

Surveyors and engineers often use the concept of the geoid, a hypothetical Earth surface that represents the mean sea level. It is useful because it represents the horizontal everywhere, and gravity acts perpendicular to it. Water will not flow in an aqueduct, for instance, if its pipes are perfectly aligned along the geoid.

Seasons. Earth’s orbit is almost circular, with its distance from the Sun varying by only about 3 per cent over the course of a year. This means that the solar energy received on Earth changes by about 6 per cent. However, this is not the cause of the seasons – hot summers and cold winters are due to the 23.5° tilt of the Earth’s rotation axis.

The tilt makes more sunlight fall on the northern hemisphere than the southern hemisphere during the northern summer, the peak occurring on the summer solstice on 20/21 June. More solar energy falls on the southern hemisphere in December, peaking at the solstice on 21/22 December. Sunlight is equal in both hemispheres at the vernal or spring equinox [20/21 March] and the autumnal equinox [22/23 September].

Earth’s large axial tilt also means that any regions inside the Arctic and Antarctic circles, at latitudes of more than 66° North or South, will experience a period of permanent sunlight in summer and permanent darkness in winter.

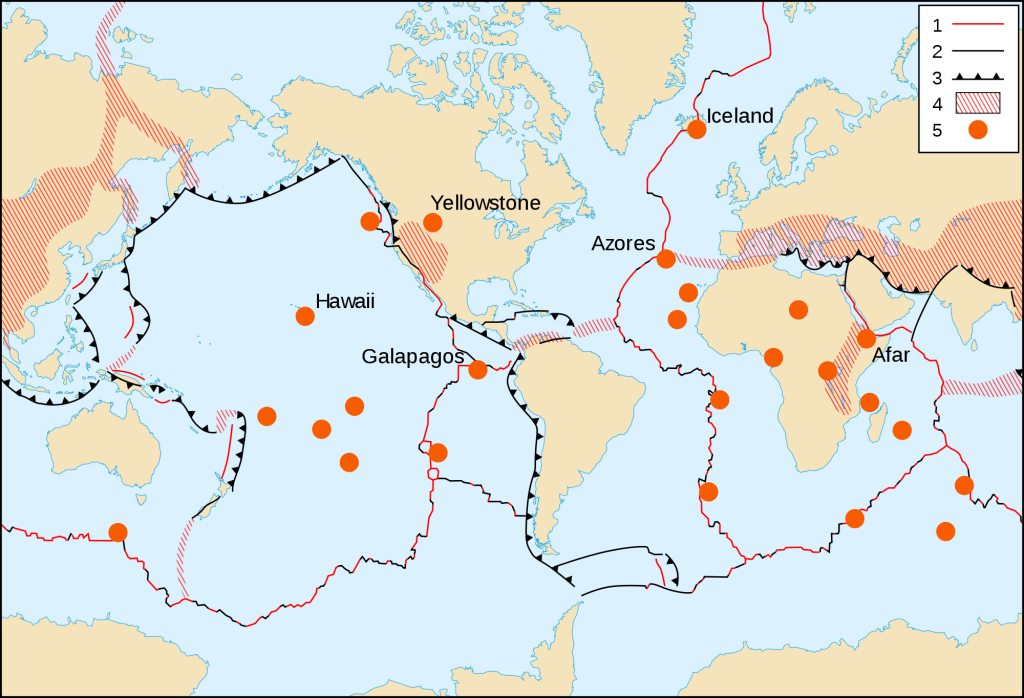

Plate tectonics. Plate tectonics describes the movement of the Earth’s lithosphere, consisting of its rigid crust and upper mantle. This is the driving force behind continental drift, which saw a single vast supercontinent called Pangaea [see above] break up roughly 250 million years ago. This fragmentation led to the forming of the now familiar continents such as Africa and Europe.

The lithosphere divides into several major tectonic plates that move on the mobile mantle underneath. Dense old lithosphere sinks into the deep mantle at “subduction zones”, while new crust is formed by volcanic eruptions at mid-ocean ridges. The speed of tectonic plates is typically very slow – roughly as fast as your fingernails grow.

Where tectonic plates collide, mountain ranges can form, while divergent faults occur when plates move apart. “Transform boundaries” form where plates are sliding past each other. Earthquakes and volcanoes usually coincide with plate boundaries, although volcanism can also occur at “hotspots” within plate interiors, which overlie hot mantle plumes.

Faults. A fault is a fracture or discontinuity in rocky terrain where two masses of rock have moved relative to each other. Some faults are tiny, but others are part of vast fault systems criss-crossing the Earth at the boundaries of major tectonic plates. The sudden movement of faults causes earthquakes. Faults that have horizontal movement are called strike-slip faults, while those with primarily vertical movement are called dip-slip faults.

A divergent fault is one where two plates gradually move apart, sometimes creating mid-ocean ridges as underlying magma wells up through cracks in the oceanic crust and cools. Tectonic plates collide at convergent faults. Sometimes, this makes oceanic crust slide beneath the other plate, forming a “subduction zone”. The collision of two continental plates can drive up huge mountain ranges like the Himalayas.

A transform fault is one where tectonic plates slide past each other horizontally. A classic example is the San Andreas Fault in California, which has triggered several major quakes.

Earthquakes. Earthquakes occur when a sudden release of energy in the Earth’s crust shakes the ground by generating seismic waves. They happen because tectonic plates don’t glide over each other smoothly without friction. Instead, their roughness makes them lock together, allowing stresses and strains to build up until they lurch sharply.

Divergent faults pulling apart trigger “normal” earthquakes, convergent plates cause “thrust” earthquakes and transform faults, where plates slide past each other, cause “strike-slip” quakes. Traditionally, the power of earthquakes has been measured on the Richter Scale, and quakes with “magnitudes” above nine devastate areas thousands of kilometres across.

When an earthquake occurs under the sea, the seabed sometimes moves enough to trigger tsunamis, giant waves that can devastate coastal regions. An earthquake in December 2004 off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, caused the worst tsunamis in recorded history, killing more than 230,000 people in 14 countries.

. Divergent fault: two sides of fault move vertically in relation to each other

. Convergent fault: two sides of fault move horizontally towards one another

. Transform fault: two sides of fault slide past one another

Volcanoes. Volcanoes form when hot molten rock, or magma, wells up through the Earth’s crust due to heating from the mantle beneath. They’re often found along boundaries where tectonic plates converge or diverge – for instance, along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where plates are pulling apart.

Volcanoes also occur at “hotspots” far from plate boundaries, where the crust overlies a hot mantle plume. Eruptions at an undersea hotspot formed all of the Hawaiian islands, for instance. Volcanoes often form conical mountains that spew lava, ash and gases from a collapsed crater, or caldera, at the top, but others have rugged peaks formed by lava domes.

“Pyroclastic flows” of searing hot gas, ash and rock often speed away from an erupting vent at up to 150 km/h [90 mph], hugging the ground. Volcanoes also eject volcanic “bombs”, blobs of molten rock up to several metres wide, which cool and crust over before hitting the ground. The most-deadly eruption in recorded history was that of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora in 1815, which killed more than 71,000 people.

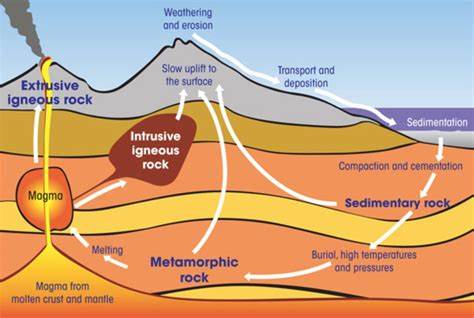

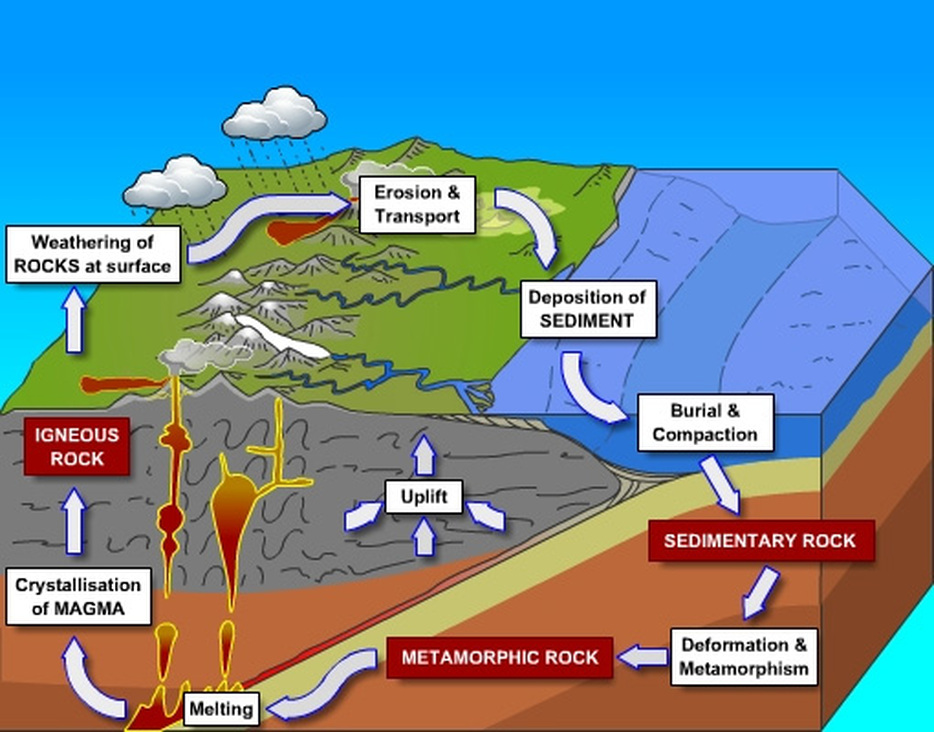

Rock types. Rocks are classified into three main groups: igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks form when hot molten rock, or magma, rises through the Earth’s crust, then cools and solidifies. When magma slowly cools deep underground, large crystals grow inside it, creating coarse-grained rock such as granite, while rapid cooling at the surface creates fine-grained rock such as basalt.

Sedimentary rocks form on the Earth’s surface. They are layered accumulations of sediments including rock fragments, minerals and animal and plant material. One example is sandstone, which forms when sand settles out of water, then becomes compacted by overlying deposits. Sedimentary rocks probably make up only about 5 per cent of the Earth’s crust, forming a thin veneer over igneous and metamorphic rocks.

Metamorphic rocks were once sedimentary or igneous rocks, but their densities increased, and their compositions changed when they were pulled deep down into the Earth’s crust and subjected to high pressures and temperatures.

The rock cycle. The rock cycle describes the endless natural recycling processes that rocks undergo on the restless Earth, continually changing over millions of years due to processes such as erosion and tectonic plate motions. The rock cycle is particularly active when tectonic plates meet.

The cycle begins with magma, fluid or mushy hot rock beneath the Earth’s surface, which cools and crystallises to form igneous rocks. These rocks can return to their roots as magma by “subduction”, being dragged back down through the crust to melt again. Alternatively, burial of igneous rocks can compress and heat them to form metamorphic rock. At the Earth’s surface, rocks are weathered and eroded into fragments and grains. Rivers and streams sweep these particles away and deposit them in lakes and seas, beginning the process of sedimentation that creates sedimentary rock.

Continental crust recycles very slowly, and Earth’s current continental crust is typically about 2 billion years old, while the oldest oceanic crust is only about 200 million years old.

Fossils. Fossils are the remains of animals, plants and other living organisms that have been preserved for thousands of years inside sediments, which have gradually replaced their tissues with minerals.

Fossilisation can preserve the remains of animals or plants that are buried soon after they die. For instance, the soft parts of a dead fish might rot away while its skeleton becomes buried in muddy or sandy sediments, retaining its structure as the sediments are compacted into stone. Minerals gradually replace the skeleton by filling voids left as the skeleton slowly dissolves. Millions of years later, this skeleton “copy” can become exposed through mountain or cliff uplift and erosion.

Like living organisms, fossils can range from microscopic single cells to gigantic dinosaurs and trees. Fossils may also preserve the marks left by animals in sediments, such as footprints of our early human ancestors. The oldest known fossils are “stromatolites”, fossilised colonies of microbes that date back for 3.4 billion years or more.

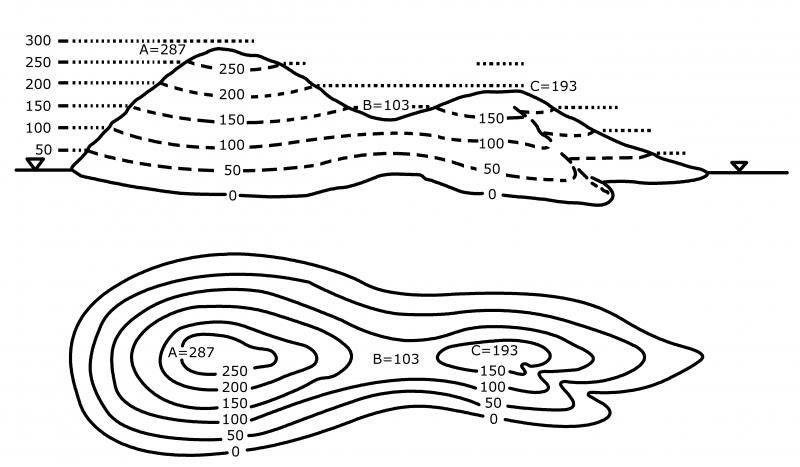

Topography. In geography, topography is the study and mapping of Earth’s surface shape and features in three dimensions. Topographic maps, or relief maps, record the height of terrain using contour lines, with each contour line tracking land of equal height. Mountains appear as concentric loops, the steepest slopes indicated by the most tightly packed contours.

Detailed information about terrain and surface features is essential for planning and executing any major projects in civil engineering or land reclamation, for instance. “Photogrammetry” is a traditional technique for locating 3D coordinates of points on the ground by comparing two or more aerial photos taken from different angles.

Digital data for precise relief maps of the Earth’s surface come from satellite radar mapping of the land, while sonar surveys from ships can measure the terrain on the ocean floors. Airborne “lidar [Light Detection and Ranging] systems can also map the detailed heights of forest canopies and glaciers, for instance, by measuring reflected visible laser light.

Continents. The continents are the seven biggest landmasses on Earth: Asia, Africa, North America, South America, Antarctica, Europe and Australia. They make up just over 29 per cent of the Earth’s surface. Oceans or seas separate most of the continents, except for Europe and Asia, which are often considered to be a single continent called “Eurasia”.

Close to 40 per cent of the Earth’s total land surface is used for crops and livestock pasture, while roughly a quarter is mountainous. Forests cover about a third of the land. In the tropics, most forests are lush tropical rainforest, with annual rainfall above about 1.8 m [6 ft]. Deserts are dry and arid areas with less than 25 cm [10 in] of rainfall each year, making vegetation sparse or almost non-existent. Hot and cold deserts take up about one-fifth of the Earth’s land surface.

“Temperate” regions with relatively mild climates lie between the permanently hot tropics and the polar regions, while vegetation-poor “tundra” with permanently frozen subsoil dominates the ice-free land at high northern latitudes.

Oceans. The oceans are vast bodies of salt water that cover almost 71 per cent of the Earth’s surface. They are usually divided into five major oceans: the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Southern Ocean and the Arctic Ocean.

Nearly half of all oceans, by area, are more than 3km [9,800 ft] deep. The deepest point overall is in the Mariana Trench in the Pacific south of Japan, which reaches down about 11km [36,000 ft]. Two oceanographers, Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard, reached the bottom of the Mariana Trench in a small submersible in 1960 – a feat no one else has achieved since.

Ocean currents act like giant conveyor belts to transfer heat from the tropics to the poles. Cold deep water rises and warms in the central Pacific and the Indian Ocean before heading to high latitudes where it sinks and cools. An important ocean current system stretching from the southeast US to northwest Europe incorporates the Gulf Stream and the North Atlantic Drift. This helps to keep northwest Europe’s climate relatively warm.

Surface water. About 97 per cent of all water on Earth is in the salty oceans, while only about 2.5 per cent is fresh water. Most of that is tied up in the ice caps or lies underground. In fact, only about 0.3 per cent of Earth’s fresh water is in rivers and lakes, the sources of most water we use in everyday life.

When the Sun heats water in the oceans, it evaporates as water vapour that rises and condenses into clouds, before falling as precipitation including rain and snow. Ice can be stored for thousands of years in the ice caps and glaciers, which contain about 70 per cent of Earth’s fresh water.

Rainwater runs off land into rivers that flow to the oceans or into largely freshwater lakes. There are many types of lakes, including “oxbow lakes” that form when the force of flowing water gradually exaggerates a meandering curve until it cuts off from the main river channel. Lake Superior on the US-Canada border is often regarded as the largest freshwater lake by area, covering 82,400 square km [31,820 miles].

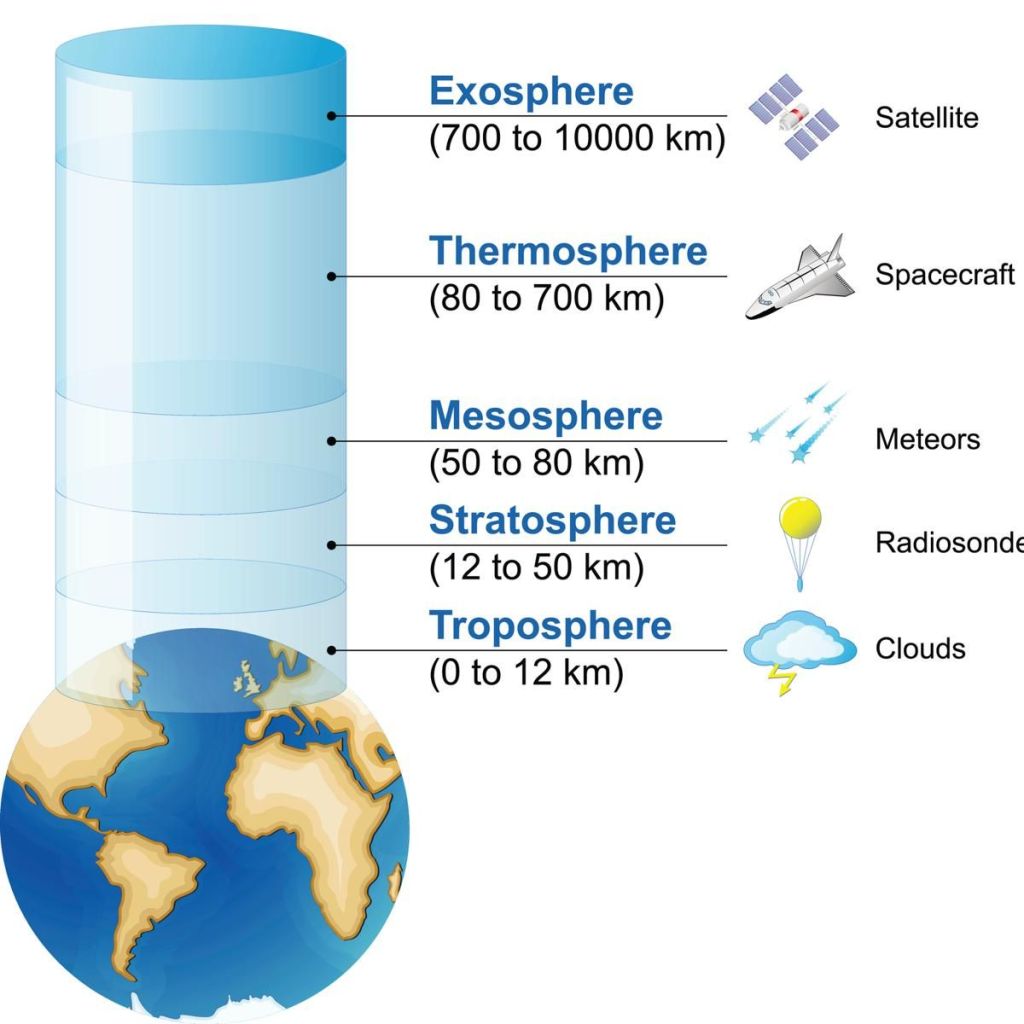

Atmospheric structure. The atmosphere is the shroud of gases around the Earth, held in place by gravity. It plays a vital role in making our planet hospitable to life, providing air to breathe and preventing large temperature swings between night and day.

The atmosphere is mainly composed of nitrogen [78 per cent] and oxygen [21 per cent], but its composition changes with height. The lowest layer, the troposphere, is the densest and contains roughly 80 per cent of the atmosphere’s mass. The next layer is the stratosphere, and this contains the ozone layer, which absorbs most of the ultraviolet light from the Sun that would otherwise be harmful to life. The outermost atmospheric layer is the thin exosphere, composed mainly of hydrogen and helium.

The Earth’s atmosphere looks blue because it scatters blue sunlight better than red sunlight, sending blue light photons in every direction. Sunrises and sunsets appear red because the Sun is on the horizon, so its light passes on a long path through the atmosphere where more blue light is removed.

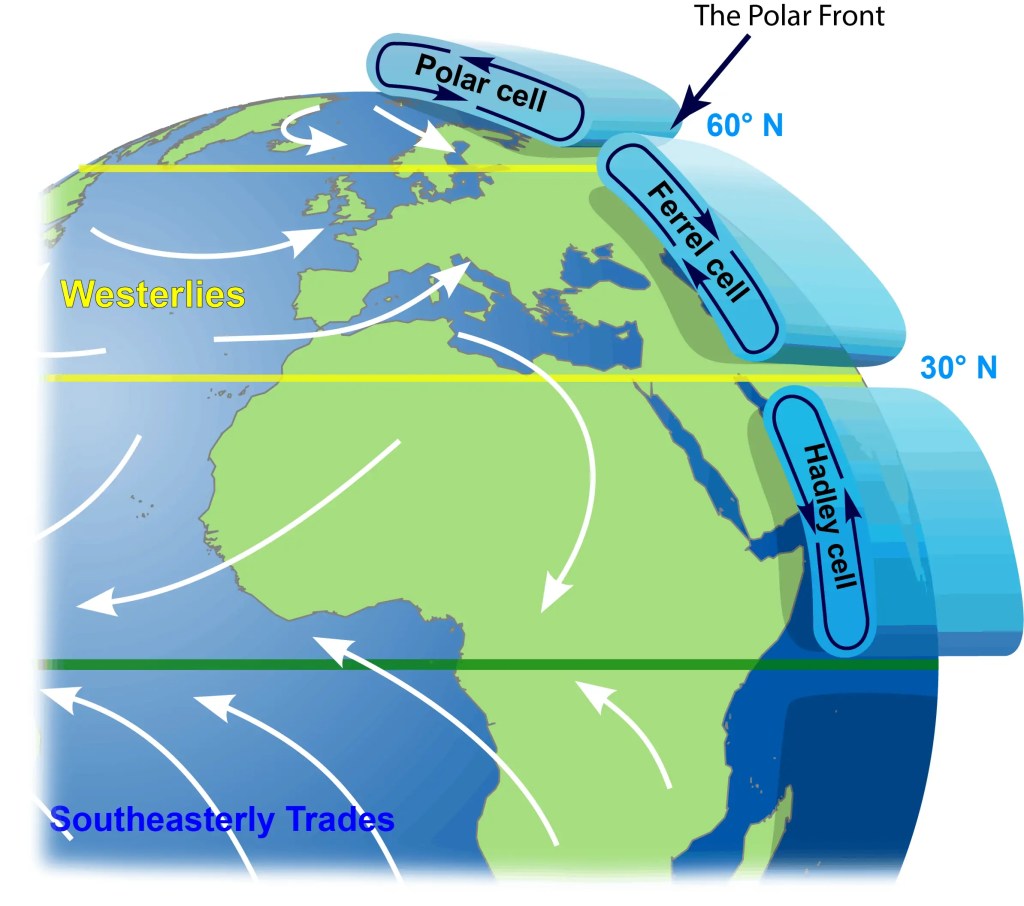

Atmospheric circulation. The atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air that distributes heat across Earth’s surface. It is dominated by “Hadley cells”, huge convection loops described by English lawyer and scientist George Hadley in the early 1700s.

Hadley cell circulation begins with moist, hot air at the equator rising and moving polewards, then descending at latitudes of about 30° North and South. Some of the descending air travels across the surface back towards the equator, creating the “trade winds” that also veer towards the west due to the Earth’s rotation. The polar cells are high-latitude convection loops at more than 60° North and South.

Ferrel cells, first proposed by 19th-century American meteorologist William Ferrel, are convection cells that operate at mid-latitudes but rotate in the opposite direction to polar cells and form westerlies due to the Earth’s rotation. The jet streams – mainly the “polar jets” and “subtropical jets” – are high-altitude flows of fast-moving air that form at the boundaries between the cells and rotate towards the east.

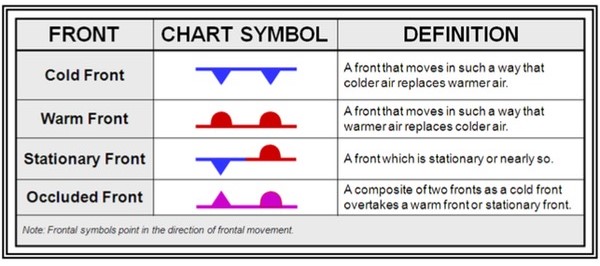

Weather fronts. In meteorology, weather fronts are boundaries separating masses of air with different density, temperature and humidity. Their approach signals the onset of a change in weather. For instance, when a cold front moves under a mass of warm moist air, the warm air rises, and the moisture can condense into heavy rainclouds.

Cold fronts move faster than warm fronts and produce more sudden changes in weather because cold air is denser than warm air and replaces it rapidly. On weather maps, cold fronts are shown as lines of blue triangles pointing in the direction of travel. Light rainfall often signals the approach of a warm front, depicted as a line with red semicircles.

An “occluded front” forms when a cold front overtakes a warm front. A “stationary front” is effectively a stalemate between two fronts, neither strong enough to replace the other. It tends to hang around in the same place for a long time, often delivering rainy weather for several days.

Clouds. A cloud is an opaque mass of water drops or ice crystals suspended in the atmosphere. Clouds form because sunlight warms the Earth’s surface and evaporates water. Moist, warm surface air rises to higher altitudes where the water vapour condenses onto tiny particles like dust or salt, forming liquid droplets or ice crystals if it is cold enough. Eventually, these become too large to be supported by upward air currents and fall as precipitation.

Cumulus clouds are puffy, dense clouds that sometimes look like cotton wool. They grow upwards and can develop into giant cumulonimbus clouds that trigger thunderstorms. Cirrus clouds are thin, wispy clouds blown by high winds into long streamers. They form at high altitudes about 6 km [20,000 ft], and usually accompany pleasant weather.

Clouds with the prefix “alto” are middle-level clouds, while stratus clouds are uniform greyish ones that often cover the entire sky. All weather-related cloud-types form in the troposphere, the lowest major layer of Earth’s atmosphere.

Precipitation and fog. Precipitation is any kind of water falling out of clouds, including rain, snow, sleet and hail. It happens when air turbulence inside clouds makes small water droplets or ice particles collide, producing larger ones. When they become too large to be supported by upward air currents, they fall to the ground. [An exception is “virga”, light precipitation that evaporates before it hits the ground.]

Raindrops grow up to about 10 mm [0.4 in] across, the largest ones flattened into pancake shapes by oncoming airflow. Snowflakes can reach several centimetres wide. Hailstones grow as they repeatedly rise and fall inside a cloud by moving in and out of an updraught, and can reach more than 20 cm [8 in] wide, big and heavy enough to cause fatal injuries.

Unlike precipitation, fog is a mass of water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth’s surface – basically a low-lying cloud. The moisture often has a local source, such as a lake or marsh. Mist is thin fog that allows visibility greater than 1 km [3,280 ft].

Storms and tornadoes. A storm is any disturbance in the atmosphere that causes severe weather. Storms arise when rising hot air creates a centre of low pressure surrounded by high-pressure regions, leading to strong winds and the formation of storm clouds such as cumulonimbus clouds.

Thunderstorms occur in warm regions when humidity is high. Moist, warm air becomes unstable and rapidly rises, while cold air forms strong downdraughts beneath. The shear negative electric charge off falling water drops and ice particles causes “charge separation” with rising ones from warm air in the clouds. This is discharged in the form of lightning strikes, and heard as thunder-claps.

Tropical cyclones occur at low latitudes when air rotates around a centre of low pressure, fuelled by heat released when moist air rises and condenses. Major tropical cyclones are often called hurricanes or typhoons depending on location. Tornadoes are violent, funnel-shaped wind-storms that suck up debris and can persist for more than an hour. They are most common in the central US, in an area dubbed Tornado Alley.

Lightning. Lightning occurs during thunderstorms when an electric charge separates inside clouds. As a thunderstorm brews, water droplets in rapidly rising warm air transfer this electric charge to falling droplets and ice particles. This makes the base of a cloud negatively charged relative to the top of the clouds. Lightning happens when the resulting electric field becomes powerful enough to discharge through the cloud or to the ground.

Cloud-to-ground lightning starts when a channel of charge, usually negative, zigzags downwards in a forked pattern to the ground and connects with a “streamer” of positive charge reaching up. This creates a path for a lightning bolt that heats the air, triggering pressure waves that we hear as thunder.

The atmosphere also hosts high-altitude electrical discharges called sprites – usually red luminous glows that sometimes have bluish downward tendrils – and elves – red glows each lasting less than 0.001 seconds. Many people have observed and reported seeing hovering, glowing spheres of “ball lightning” at ground level, but the origin of this effect is a mystery.

. Just before a lightning strike, leaders of negatively charged air start to snake down from the bottom of the cloud, while positively charged leaders snake up from the ground (from roof or tree tops, for example).

. When a leader from the cloud meets a leader from the ground, current can flow along the unbroken pathway and lightning strikes. `

Climate. The Earth’s climate describes regional average weather patterns, including factors such as typical temperature, humidity, wind and rainfall at different times of the year. A host of factors influence these patterns, including latitude, altitude and the location of a landmass relative to an ocean.

The most commonly used climate classification system is the Köppen system, published by German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1884. This assigns all regions to five main climate categories. Tropical regions have sea-level temperatures averaging 18°C [64°F] or more all 12 months of the year, while dry climates receive less water from precipitation than they can potentially lose through processes like evaporation.

Temperate regions have seasonal temperatures averaging above 10°C in summer and above -3°C in winter, while continental climates differ by having a coldest monthly average below -3°C. Polar regions (or Alpine) have average monthly temperatures below 10°C all year round. These broad categories have 28 subcategories in total.

Climate change. Many factors have altered the Earth’s climate over time, including tiny periodic variations in its orbit and the orientation of its spin axis. Throughout much of Earth’s history, global average temperatures were more than 5°C warmer than today and the poles were ice free. At other times, the world has been plunged into ice ages.

Climate change has also occurred in recent times. Between the mid-1500s and the mid-1800s, a period dubbed the “Little Ice Age”, average temperatures were roughly 1°C cooler than today. One possible reason is that atmospheric ash from volcanic eruptions cooled the planet by blocking sunlight.

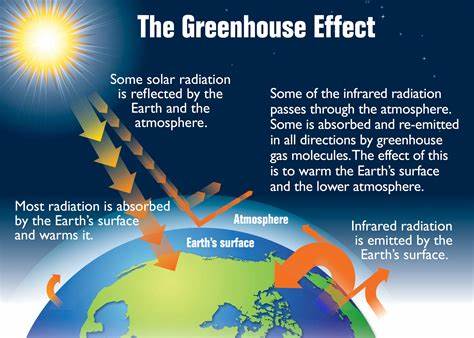

Average temperatures increased by 0.6–0.9°C during the 20th century. Most scientists believe this is due to human activity, especially through the burning of fossil fuels. This releases greenhouse gases, which trap some solar energy that would otherwise escape into space. Temperatures could climb by several degrees during the 21st century, causing catastrophic sea-level rise and triggering frequent droughts and storms.

Ice ages. In ancient history, the Earth’s poles were sometimes ice free, but during ice ages, cool climates allowed vast ice sheets to grow over the continents. There are many natural causes for this continuous climate change, including tiny changes in the tilt of Earth’s spin axis and movements of the continents.

Evidence for ice ages comes from geological features such as valleys carved by creeping glaciers as well as deep-drilled polar ice cores, which contain bubbles of ancient air that preserve temperature information. The fossil record shows many organisms spread to warmer regions during cold periods.

There have been at least five major ice ages so far. The earliest well-established one occurred 2.5 to 2.1 billion years ago, while a cold period 850 to 630 million years ago may have seen “Snowball Earth” conditions with ice reaching the equator. The current “Quaternary glaciation” began 2.58 million years ago. The Earth is now in an “interglacial period”, a relatively warm period within an ice age, while the last especially cold glacial period ended roughly 10,000 years ago.

. During the last glacial of Earth’s most recent ice age, glaciers extended across much of northern North America, Europe and Asia, as well as spreading out from the Andes of South America and becoming thicker across Antarctica.

Climate engineering. Climate engineering describes proposed attempts to mitigate global warming on Earth caused by our use of fossil fuels. Each year, fossil fuel consumption releases billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas.

Some climate engineering proposals would reduce the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere directly – for instance, by using industrial plants to mop up the gas, liquefy it and then pump it underground or into the ocean floor. Another idea is to add iron to the oceans, stimulating the growth of ocean phytoplankton that use iron as a nutrient and absorb carbon dioxide as they grow.

Another possible approach is to cool the Earth by cutting down the amount of solar energy reaching the atmosphere. Mirrors on spacecraft could reflect sunlight away, or aircraft could seed the atmosphere with aerosol particles that block out light. These ideas are all in an early research phase – they remain largely unproven as solutions to global warming and could, arguably, do more harm than good.

Climate engineering techniques:

. Cloud seeding

. Giant reflectors in orbit

. Aerosols in stratosphere

. Tree planting

. Greening deserts

. Iron fertilisation of sea

. Liquid carbon dioxide pumped into rocks

. Liquid carbon dioxide pumped into deep ocean

This completes Science Book (Earth Science). Amendments to the above entries may be made in future.