– ‘Science Book: Information Technology’ seeks to address all of the fundamental concepts within the field of Information Technology and Computer Science. This is Book 5 in the science series on this site.

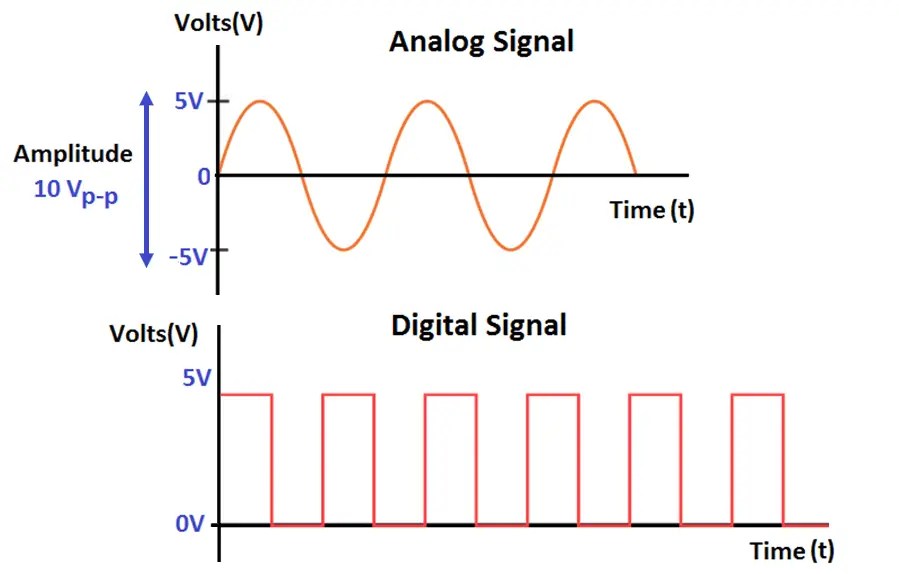

Analogue and digital computing. Analogue computers are old-fashioned ones that work with continuously variable quantities like the strength of an electric current or mechanical rotation of a dial. Modern computers are based on digital technology. Information is represented by bits and bytes, sequences of binary 1s and 0s. Fundamental to the technology is the idea of on/off, true/false.

Analogue computers date back to ancient times, the oldest known example being the Greek Antikythera mechanism, which dates to between 150 and 100 BC and was designed to calculate astronomical positions. In the mid-1900s, scientists developed analogue computers with electrical circuits that could perform calculations. These computers were still in use in the 1960s and performed many of the calculations needed to plan NASA’s Apollo spacecraft missions to the Moon.

Early digital computers used bulky “thermionic valves” and later transistors to switch currents to perform calculations. Microchips – tiny electrical circuits – revolutionised computer technology, paving the way for small, powerful desktop computers.

Microchips. A microchip or integrated circuit is a tiny electrical circuit on a semiconductor silicon wafer. Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments in the US invented the first microchip in 1958, and today they are used in all common electronic devices including computers, mobile phones and sat-nav systems.

Digital computers perform calculations using transistors that can switch between two states, on and off, representing the binary digits 0 and 1. Microchips miniaturise the electronic circuitry required. They are cheap to make because the circuitry is “printed” onto semiconductor wafers by photolithography, rather than being constructed one transistor at a time. A “photo-resist” coating is applied to the wafer and ultraviolet light etches out the circuit pattern. Then another etching process lays down conducting metal pathways.

Modern integrated circuits that are just 5 mm [0.2 in] square host millions of transistors, each much tinier than the width of a human hair. They can switch on and off billions of times a second.

A complete microchip “package” allows the complex electronics of the integrated circuit to interface with other elements of a device.

The pins of a microchip slot into a printed circuit board (PCB) and there is fine “bond wires” of aluminium, copper or gold that connect the top of the pins to the integrated circuit. The surface of the microchip is covered in an insulating substrate.

Computer algorithms. A computer algorithm is a sequence of instructions designed to solve a problem. It might specify the way a computer should calculate monthly payments for employees, for example, and how it should display the results. Real computer algorithms are normally very complicated, but this simple examples outlines the steps to turn a daylight-sensing streetlamp on at night:

[1] Is it dark? If yes, go to [2], if no, go to [3]

[2] Turn on the light. Go to [3]

[3] End

“Genetic algorithms” are ones that evolve in a process that mimics biological natural selection. An algorithm designed to perform a certain task is tested and rated for its success, then allowed to “breed” with other algorithms by mixing up their attributes. The most successful “offspring” algorithms then breed, and the process repeats until the computer “evolves” the best algorithm for the job or task at hand.

Neural networks. In computer science, a neural network is an information-processing concept inspired by the way biological nervous systems process information. Many processing elements are connected like a network of biological neurons, and they work in unison to solve specific problems.

Conventional computers use algorithms to solve a problem, but this restricts their capabilities to problems we already know how to solve. Neural networks are like “experts” in the information they analyse and are good at finding patterns in a large jumble of data. A neural network could compare the features of thousands of Hollywood movies in a database with their box-office takings, for instance, and pinpoint the factors that distinguish the hits from the flops.

Another application of neural networks is in face-recognition software. Computers can be trained to recognise a face by analysing images and comparing positions of features such as eye corners, but neural networks can learn which features are most useful for matching a face to images in a database.

A simple neural network consists of numerous interconnected processing units or “synapses”, each of which stores parameters known as weights. Data fed to input synapses is passed to one or more “hidden” layers, whose weights are calculated using (learning) algorithms. The results of calculations by the hidden layers are then synthesised by output synapses.

Quantum computing. A quantum computer is one that would use the physics of quantum mechanics [see: Science Book: Physics] to increase its computational power beyond that of a conventional computer. Such instruments are still in a very early research phase.

Conventional computers store data in a binary series of 0s and 1s. Instead, a quantum computer would store information as 0,1 or a quantum superposition of the two. These “quantum bits” or qubits, would allow much faster calculations. While three conventional bits could represent any number from 0 to 7 at one time, three qubits could represent all these numbers simultaneously. This means a quantum computer could tackle several calculations at the same time and solve problems that would keep today’s supercomputers busy for millions of years.

Experimental quantum computers have used a few qubits to perform simple calculations like multiplying 5 by 3. It’s not clear whether they will become a practical option because they rely on complicated and delicate procedures such as quantum entanglement [see also Science Book: Physics] to couple the qubits together.

One-way physicists model the exact mixing of 1 and 0 in a quantum “qubit” is to think of it as the latitude on a sphere, with a “north pole” equivalent to a value of 1 and a “south pole” equivalent to value 0. Superpositions – a mix of 1 and 0 values – can be considered as intermediate latitudes. The measurement process collapses the qubit into a classical value of 1 or 0, with the probability of each value given by the surface area on the opposite side of a qubit’s latitude.

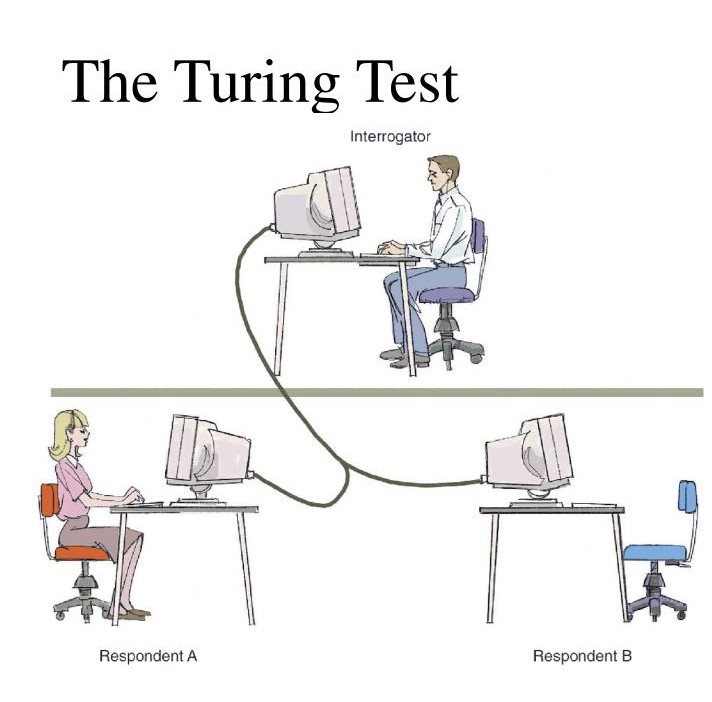

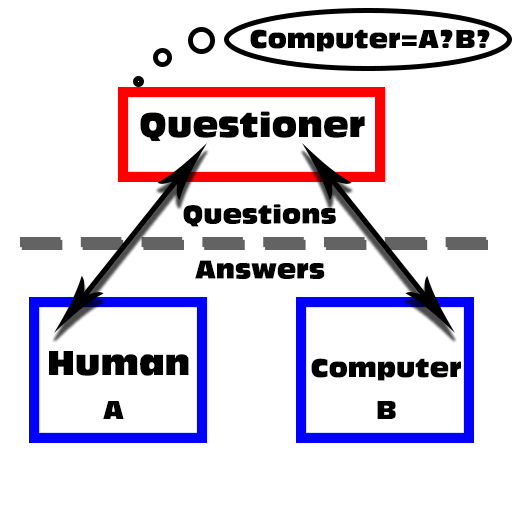

Turing test. The Turing test is a measure of a machine’s ability to demonstrate intelligence. English mathematician, computer pioneer and Second World War code breaker Alan Turing proposed the test in the 1950s. Basically, it suggests that a computer has achieved human intelligence if it convincingly responds like a person.

Turing proposed an experiment in which a volunteer sits with an experiment manager behind a screen. On the other side, out of sight, a second volunteer asks questions. The first volunteer and a computer both answer with text messages, and the manager decides at random which of the two responses the questioner will receive. If the questioner can’t distinguish the human responses from the computer ones, the computer has achieved human intelligence.

Turing predicted that machines would eventually pass the test. Various commercial text and email programs regularly trick people into thinking they’ve communicated with a person, but no computer has yet passed a rigorous Turing test.

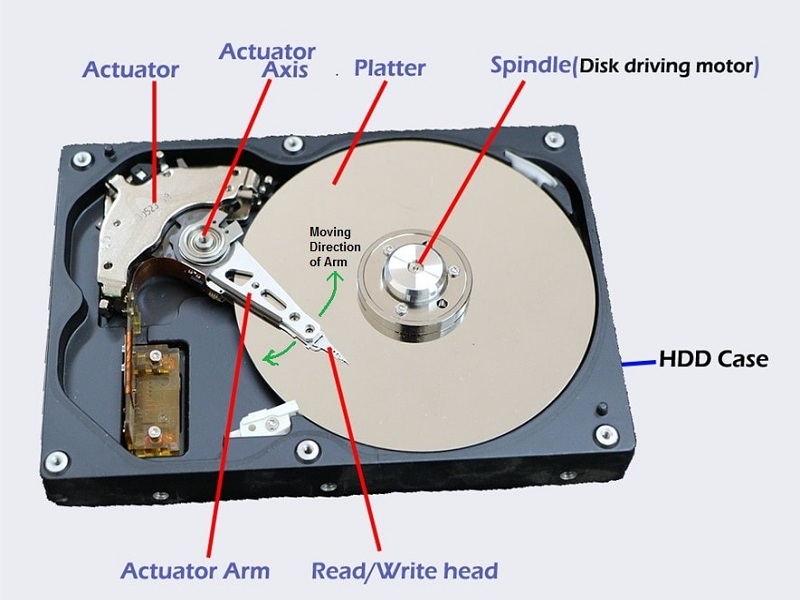

Hard drives. Hard disks in computers and servers store changing digital information in a fairly permanent form. This gives computers the ability to “remember” data even when they’re switched off. They consist of several solid disks or “platters” on which data are stored magnetically, and a read/write head to record and retrieve information.

The technology was invented in the 1950s and later took the name “hard disks” to distinguish them from floppy disks, which stored data on flexible plastic film. The platters in a hard disk are usually made of aluminium or glass with a coating of magnetic recording material, which can be easily erased and rewritten and preserves information for many years.

When the drive is operating, the platters typically spin 7,200 times a minute. The arm holding the read/write heads can often move between the central hub and the edge of the disk and back up to 50 times per second. Some desktop computers now have hard disks with more than 1.5 terabytes [1.5 million million bytes] of memory.

. Hard Disk Drive (HDD) is a magnetic storage which can store and retrieve digital information. It uses a magnetic rotating disk on which data gets stored.

. The magnetic disk is called a Platter. It rotates through a spindle (a driving motor). Just above the disk there is a metallic arm called the Actuator arm which moves side-ways (Left-right). The Actuator arm is connected to the Actuator which controls its movement.

Flash memory. Like hard disks, flash memory stores digital information and “remembers” it even when the power is switched off. Unlike hard disks, flash memory does not have any moving parts. It doesn’t mind a good hard knock and can withstand large temperature variations, and sometimes even immersion in water. That makes it the ideal memory for portable devices.

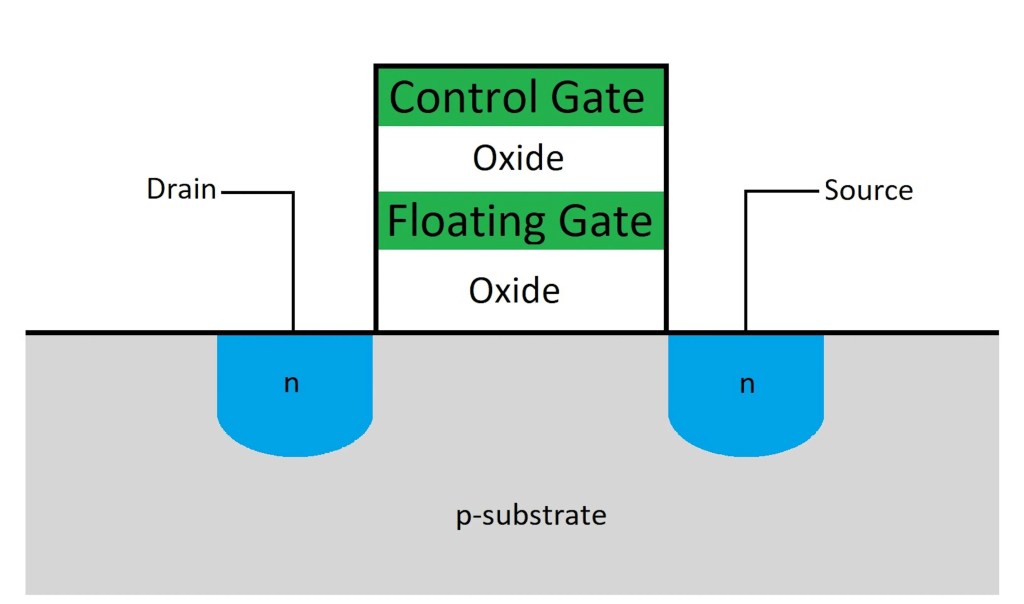

Flash memory works by switching transistors on and off to represent sequences of 0s and 1s. Unlike conventional transistors, which “forget” information when the power is off, the transistors in flash memory have an extra “gate” that can trap electric charge, registering a 1, until another electric field is applied to drain the charge and return the bit to 0.

Flash memory is used in mobile phones, MP3 players, digital cameras, and portable memory sticks, which are often used to back up files or transfer files between computers. Some memory sticks have storage capacities of 32 gigabytes, enough to store around 20 hours of video.

Optical storage. Optical storage refers to types of memory, such as CDS and DVDs, that are read by a laser. Today, desktop computers have drives that both read and write these media.

Both CDs and DVDs have a long, spiralled track up to around 12 km [7.5 miles] long. Mass produced CDs and DVDs have little bumps around the track that encode digital data as a series of 0s and 1s. To read the data, a red laser bounces light off the bumps and a sensor detects height changes by measuring the reflected light.

CD burners have been reasonably standard in personal computers. Write-once CDs are coated with a layer of see-through dye, and a laser burns data onto the disc by turning this dye opaque. Rewritable CDs use a more complicated chemical trick that allows data to be erased again by laser heating. Blu-ray discs can store even more information than DVDs because they are read with a blue-violet laser that has a shorter wavelength than a red laser, making it possible to focus the laser spot with much greater precision.

Holographic memory. Holographic memory might one day revolutionise high-capacity data storage. Today, magnetic storage and optical storage are the usual ways of storing large amounts of data, recording individual ‘bits’ on a surface and reading them one bit at a time. The holographic technique would record information in a 3D volume and read out millions of bits simultaneously. This would speed up data transfer enormously.

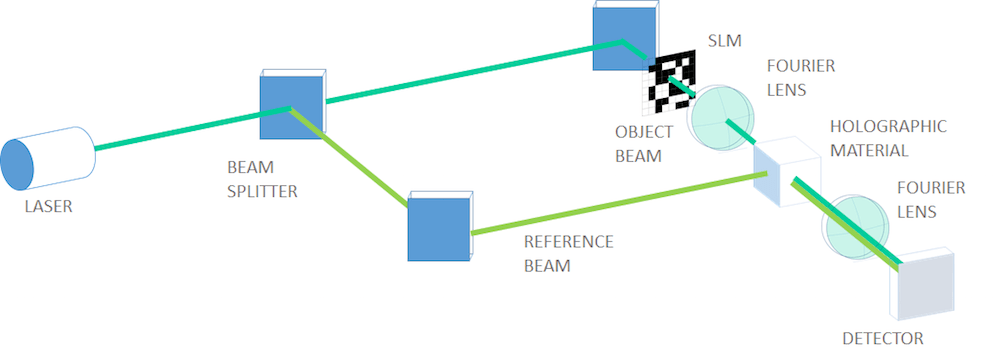

To record holographic data, a laser beam is split into two, with one ray passing through a filter carrying raw binary data as transparent and dark boxes. The other “reference” beam takes a separate path, recombining with the data beam to create an interference pattern [see: Interference described in Science Book: Physics], recorded as a hologram inside a light-sensitive crystal. To retrieve the data, the reference beam shines into the crystal at the same angle that it stored the data, to hit the correct data location inside.

Several companies hope to develop commercial holographic memory, which could one day store many terabytes [millions of millions of bytes] of data in a crystal the size of a sugar cube.

Radar. Radar is a technique for detecting objects and measuring their distances and speeds by bouncing radio waves off them. It developed rapidly during the Second World War and is still used in a wide range of applications, including air traffic control and weather forecasting as well as satellite mapping of the Earth’s terrain and that of other planets.

Radar stands for “radio detection and ranging”. A radar dish, or antenna, transmits pulses of radio waves or microwaves that reflect off any object in their path. The reflected part of the wave’s energy returns to a receiver antenna, with the arrival time indicating the object’s distance. If the object is moving towards or away from the radar station, there is a slight difference in the frequencies of the transmitted and reflected waves due to the Doppler effect [see: Science Book: Physics]

Marine radars on ships prevent collisions with other ships, while meteorologists use radar to monitor precipitation. Similar systems operating with visible laser light are called lidar, and can measure details with higher precision.

Sonar. Sonar is a technique that ships use to navigate and detect other vessels, or to map the ocean floor, using sound waves. “Passive” sonar instruments listen out for the sounds made by other ships or submarines, while “active” sonar systems emit sound waves and listen for the echoes.

Sonar stands for “sound navigation and ranging”, and the first instruments developed rapidly during the First World War for detection of enemy submarines. Active sonar creates a pulse of sound, often called a ping, and then listens for reflections of the pulse, the arrival time of the reflections indicating the distance of an obstacle. Outgoing pings are single-frequency tones or changing-frequency chirps, which allow more information to be extracted from the echo. Differences in frequency between pings and echoes can allow measurement of a target’s speed, thanks to the Doppler effect.

Fishing boats use sonar to pinpoint fish shoals, while some animals, including bats and dolphins, use similar natural echolocation to navigate or locate mates, predators, and prey.

Internet and World Wide Web. The Internet is a global system of interconnected computers that use the “Internet Protocol Suite” as a common language to speak to each other. It’s a vast network formed by myriad smaller networks run by organisations including private companies, universities and government bodies, linked together by fibre-optic cables, phone lines and wireless technologies.

The World Wide Web, or usually just the Web, is a way of handling documents over the Internet. Web browser software allows users to view pages containing text, images, videos and other multimedia and jump between them via “hyperlinks”. English computer scientist Tim Berners-Lee is credited with inventing the Web in 1989 while at CERN, the European centre for particle physics on the French-Swiss border.

The main mark-up language for Web pages is HTML [hypertext mark-up language], which uses tags at either end of text phrases to tell a Web browser how to display them – for instance, as a clickable hyperlink.

Internet security. The Internet allows easy transfer of information, but it also allows the spread of “malware” – programs written with malicious intent. Computer viruses are harmful programs that can transfer between computers, aiming to delete files or disable operating systems like Microsoft Windows.

Other forms of malware includes “spyware”, which might stealthily install itself on a computer and transmit the user’s secret passwords to fraudsters, while a computer “worm” self-replicates and sends copies of itself to other computers on a network. Networked computers need constantly updated antivirus software to detect and remove new malware, as well as “firewalls” that prevent unauthorised access from the outside.

Denial-of-service (DOS) attacks attempt to make an organisation’s website useless by bombarding it with so many communication requests that it can’t cope with legitimate traffic. Fraudsters install software agents called bots to launch attacks on specific sites, or make bots infect computers by stealth. Many countries deem denial-of-service attacks a criminal offence.

In a denial-of-service attack, the attacker hijacks the computers of other users by spreading malware. On command, the resulting “botnet” bombards a remote server computer with requests for information, overloading it.

Distributed computing. A distributed computing project is one that uses many different computers working together to solve a problem, with each computer taking charge of a small piece of the overall data processing. The goal is to complete the task much faster than would be possible with a single computer.

One type of distributed computing is grid computing, in which many computers cooperate remotely, sometimes using the idle time of ordinary home computers. An example of this is the “SETI@Home” project launched several years ago. More than 8 million people are known to have signed up to download a screensaver-like program that sifts little packets of data from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico to look for unusual signals – some of which might be communications from intelligent alien civilisations – and return the results to project organisers.

Folding@home is a similar computing project that invites the public to use their computers to analyse protein folding. This could provide vital information that leads to new treatments for diseases such as cancer and Alzheimer’s.

Typically, a distributed computing network comprises a master computer. Individual jobs are sent to a scheduler which then divides jobs into many smaller tasks. The networked computers then complete the tasks and the results are returned. The final result is returned to the master computer.

Speech communications. The 1870s saw the invention of the telephone, when Scottish-born US scientist, Alexander Graham Bell transmitted speech electrically down a wire. A microphone in a handset vibrated in response to sound, creating an electrical signal by induction that travelled down a wire to cause the reverse process in a loudspeaker, with the current making the speaker vibrate to reproduce the sound.

The first commercial mobile phones were launched in the late 1970s, relaying signals wirelessly to local transmitters that passed them on to the main landline network. Phone signals today are digital, encoded as a series of 0s and 1s. The past decade or so has seen rapid growth of phone calls over the Internet (Voice over Internet Protocol or VoIP), which has drastically reduced the costs of long-distance calls.

Satellite phones are used in remote regions where there is no mobile phone signal or landline network. They communicate directly with an overhead satellite, which beams the signal back to a ground antenna where a public phone network is available.

Fibre optics. Optical fibres are thin, flexible strands of transparent material used to “pipe” light signals around a network, transmitting all kinds of data including internet traffic and phone calls. These fibres can allow faster data transfer than conventional electrical cables and can transmit signals for tens of kilometres without any amplification.

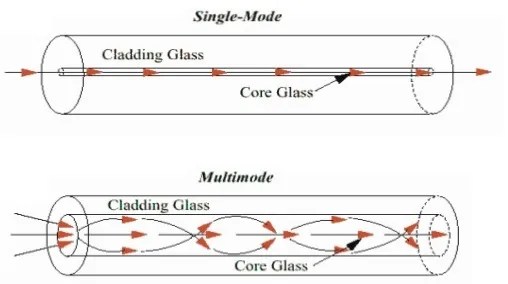

A single fibre has a thin glass or plastic core with an outer cladding of optical material that constantly reflects light back into the fibre to confine it, a process called total internal reflection. An outer plastic coating protects the fibre from moisture and damage. Typically, hundreds or thousands of fibres are bundled together in cables with an outer jacket.

Single-mode cables transmit one wavelength of light through cores thinner than a human hair, while multimode cables have wider cores that can transmit several different wavelengths. Light signals travel through them at around 200,000 km/s (450 million mph), allowing phone conversations to anywhere in the world without an annoying delay or echo on the line.

The most significant advantage of optical fibres over copper cables is that it supports extremely high bandwidth with much faster speed.

Optical fibres are much thinner than copper wires, allowing more fibres to be bundled into a given-diametrical cable. This allows more phone lines or more digital TV channels to be passed through the cable.

The loss of signal in optical fibre is less than that in copper wire. Light signals from one fibre do not interfere with those of other fibres which allows for clear phone conversations or TV reception. Optical fibres usually have a longer life cycle, lasting for over 100 years.

Light emitting sources, however, are limited to low power. Although high power emitters are available to improve power supply, this does add extra cost.

Optical fibre is also rather fragile and more vulnerable to damage compared to copper wires. Care should be exercised in not twisting or bending fibre optic cables too tightly.

The distance between the transmitter and receiver should be reasonably short, otherwise repeaters will be needed to boost the signal.

GPS. The Global Positioning System, or GPS, is a network of satellites maintained by the US government that tells receivers on the ground their precise location. Anyone with a GPS receiver, or sat-nav, can freely access it. Russia also has a satellite navigation system called GLONASS, while China and the European Union both have plans for new ones.

A sat-nav receiver calculates its position by timing signals sent by four or more GPS satellites, which tell the receiver when and where the signals were emitted. This position is shown on a screen, often with a moving map display.

At any one time there are more than 24 active GPS satellites operating in medium Earth orbit. As well as road vehicles, users include map makers, aircraft and ships. GPS also allows electronic monitoring of criminals under curfew or even pets, using devices that locate themselves using GPS and report their position via a mobile phone network, for instance. Some GPS communications are encoded for military use only.

GPS at work

. GPS satellite receiver on Earth receives four signals simultaneously, each of which was sent at a slightly different time

. The signals from the closest satellites reach receiver in shortest time

. Signal from more distant satellite takes longer to reach receiver

. Signals from three satellites reveal GPS user’s location on Earth’s surface – four signals reveal altitude as well

This completes Science Book (Computer Science). Amendments to the above entries may be made in future.