KOSOVO

Intro: Two decades since NATO intervened in Kosovo, and almost 15 years since the country declared independence, Serbia’s refusal to accept Kosovo’s sovereignty is increasing the possibility of renewed conflict in the region

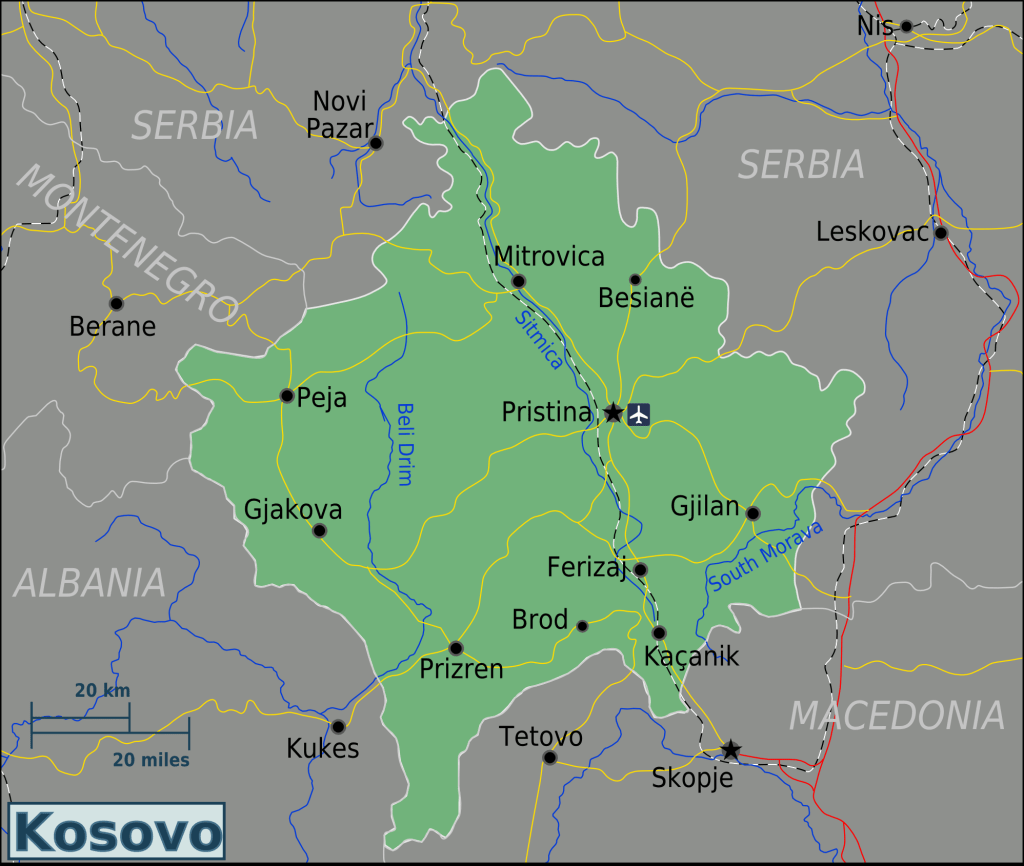

EARLY last month, ethnic Serbs in northern Kosovo – near the Serbian border – started setting up roadblocks. They were protesting against the arrest of an ethnic Serb former police officer. The situation soon escalated into a dangerous impasse between Kosovo and Serbia, with Pristina calling on NATO-led international peacekeeping forces in Kosovo (KFOR) to intervene, and Belgrade announcing its forces was on “the highest level of combat readiness” due to tensions at the border.

Following dialogue between Serbia’s President Alexandar Vucic and Kosovo’s Western partners that no arrest would be made over the incident, the protesters eventually started dismantling the roadblocks on December 29.

With the reopening of border crossings, the crisis appeared to come to an end. But the escalation in December was not the first incident that almost pushed Serbia and Kosovo into open conflict. It is unlikely it will be the last. The fragile relationship between the two neighbouring countries has been on the verge of collapse since last summer, when Kosovo’s government started taking steps to exercise sovereignty over the country’s entire territory. This included the demand that all citizens of Kosovo (including ethnic Serbs) start carrying IDs and using licence plates issued by Kosovo. In response, ethnic Serbs in the north barricaded roads and threatened violence, leading KFOR forces to start patrolling the streets in the region. A few days later, following mediation by the EU and US, Pristina and Belgrade reached a deal on ID documents but left the issue of licence plates to be resolved at a later date. That was resolved in November, with a signing of a deal that required Serbia to stop issuing licence plates with markings indicating Kosovo cities and Kosovo to cease its demands for reregistration of vehicles carrying Serbian plates.

The latest standoff at the borders came just a few weeks after this landmark deal, demonstrating quite clearly that the tensions between Kosovo and Serbia are chronic. They will not be truly resolved until mutual recognition is achieved.

Recent escalations between Serbia and Kosovo have followed a clear pattern. Kosovo attempts to exercise sovereignty over its whole territory; Belgrade responds by stoking unrest using the ethnic Serbs in the north as its proxies. The EU steps in, brokers a deal and stops the unrest from escalating into cross-border conflict. Then the cycle is repeated.

All of this shows that the recurring tensions have little to do with the practicalities of governance (such as licence plates), and everything to do with one core issue: Kosovo’s independence.

Click on page 2 to continue reading