ESSAY

THE scene is a familiar one. On the dusty and sandy plains of Afghanistan, a trail of refugees’ head for the beleaguered capital. On the streets of Kabul itself, frequent car bombs are killing members of the government along with innocent bystanders.

In the western city of Herat, people huddle in their homes as enemy rockets pound down. And in the southern province of Helmand – where hundreds of British servicemen lost their lives in recent years – dozens of civilian bodies lie rotting on the country roads.

Such is the lawless state in Afghanistan, where the resurgent Taliban have made extraordinary territorial gains in recent days. Across much of the country, their white flag now flies unchecked.

The situation in Afghanistan now is as serious as it has ever been. It’s a quarter of a century since the Taliban swept to power claiming vast swathes of land, imposing a hideously oppressive Islamist regime that treated women as slaves and banned films, TV, music and dancing.

Perhaps more significantly, in just a few weeks it will be exactly 20 years since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in New York and Washington.

It was in reaction to these atrocities that Tony Blair and George W. Bush launched Operation Enduring Freedom, promising to dismantle the al-Qaeda training camps, overthrow the Taliban and usher the Afghan people into a brave new world of democracy.

‘Operation Enduring Freedom’. How darkly ironic that mission sounds today.

For the Afghan people, the cause of freedom now hangs by a thread. Ever since the spring, when President Joe Biden announced that the last U.S. personnel would leave at the end of this month, the Taliban have swept across much of the country again.

Only a few weeks ago, U.S. intelligence analysts reportedly warned that without Western intervention, the government in Kabul might have just six months left. And now, with an estimated 85,000 Taliban fighters pressing towards the capital, that bleak prognosis looks decidedly optimistic.

Yet this is merely part of a bigger picture.

Twenty years after the War on Terror began, it’s time that we took a long, unsparing look at what it really achieved.

To revisit reports from 2001 feels like entering a different world. At the Labour Party conference, Tony Blair tells his delegates and party members that he intends to fight for freedom “from the deserts of Northern Africa to the slums of Gaza, to the mountain ranges of Afghanistan.”

“Let us re-order this world around us,” he says grandly, as if there are no limits to his ambitions. A few weeks later, his close friend Bush appears before the U.S. Congress, pledging to dismantle an “Axis of Evil” that threatens the peace of the world. He names three regimes in particular: Iran, Iraq and North Korea.

How arrogant, how criminally naïve this sounds today. The regime in Iran is more hard-line, its position apparently as secure as ever. North Korea, too, remains stubbornly defiant, having built an estimated stockpile of some 40 nuclear weapons.

As for Iraq, that desperately sad story has become only too familiar. However you measure it, the carnage since the Anglo-American invasion of 2003 has cost at least 150,000 lives, and perhaps more than a million according to some estimates.

I say ‘has cost’, rather than ‘cost’, because Iraq is still not at peace. It has never been at peace. Even now, the Baghdad government and its Western sponsors are fighting a low-level Islamist insurgency, with bombings and killings almost every single day. What, then, is the verdict on the so-called War on Terror?

There’s no doubt that some of its progenitors, at least, had noble motives. When Blair says he genuinely wanted to export Western freedoms to Afghanistan and Iraq, it’s not hard to disbelieve.

But the verdict must be utterly damning.

How can this naïve, undefined, unachievable crusade go down in history as anything other than a catastrophic failure?

Take the cost in lives first. Some 456 British servicemen and MoD civilians were killed in Afghanistan, and a further 179 in Iraq. And for what?

As the Taliban surge towards Kabul, many of the bereaved must be asking themselves: was it all in vain?

Then there’s the financial cost. In June this year, the Ministry of Defence admitted that the war in Afghanistan cost British taxpayers a staggering £22 billion, with the campaign in Iraq estimated to have cost a further £10 billion.

The grim irony, of course, is that our politicians blew all that money just before the financial crisis of 2007-08, from which the Western economy has never fully recovered. And given that Britain was about to be plunged into a long period of economic austerity, many will argue that we should have saved it for other things.

One of the greatest costs of all, though, is much harder to measure. It’s the price in moral capital and political credibility, which Britain and the U.S. are still paying to this day.

Remarkably, the invasion of Afghanistan was much closer in time to the end of the Cold War than it is to us today. The U.S. was the world’s unchallenged “hyper-power”, the march of democracy seemed unstoppable, and some American thinkers were even proclaiming the “end of history”.

The events of the last two decades, however, turned that story on its head. For the Iraqi people, the Allied invasion brought a living nightmare. For the people of Afghanistan, meanwhile, it brought a gruelling, apparently interminable campaign, which now seems likely to end as it began – with the Taliban as masters of their native land.

No wonder, then, that America’s image abroad has plummeted over the last 20 years. According to the respected Pew Research Centre, people in almost ever major Western country now have an unfavourable impression of the U.S.

In Japan, its popularity has dropped by 30 per cent since 2001. In France, too, it has fallen by 30 per cent, in Germany by almost 50 per cent. And what of faith in democracy – the one thing for which Blair and Bush claimed they were fighting?

According to an extensive international study by Cambridge University, satisfaction with democracy has never been lower. In almost every country on earth, faith in the Western capitalist model has plummeted in the last 20 years – especially among the young, to whom the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are simply incomprehensible.

And here’s another brutal irony. At the very point when Britain and the U.S. were wasting huge sums of money and with so many lives expended on their Middle Eastern misadventures, the real threats to Western democracy were hauling themselves off the canvas and preparing to rebuild.

The winners of the War on Terror were not the British and American people, and still less the natives of Afghanistan and Iraq. They were Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, the authoritarian strongmen of Russia and China, who watched with undisguised satisfaction as the Western powers discredited their own values.

That is the real legacy of the past 20 years: a shattering reversal of Western progress, for which we will be paying – quite literally – for the rest of our lives.

But perhaps it would be wrong to end by talking about ourselves. After all, the greatest casualties of the last two decades came among the people of Afghanistan and Iraq themselves, who have never known a single day of peace since the War on Terror began.

Nobody can say how their lives would have turned out if we had left well alone. No doubt they would have endured more than their fair share of tragedies anyway. Afghanistan has always been a turbulent and war-torn country.

What can be said, however, is that they have paid a terrible price for our politicians’ hubris and folly. And if we fail to learn that lesson, it would be the greatest betrayal of all.

. Appendage

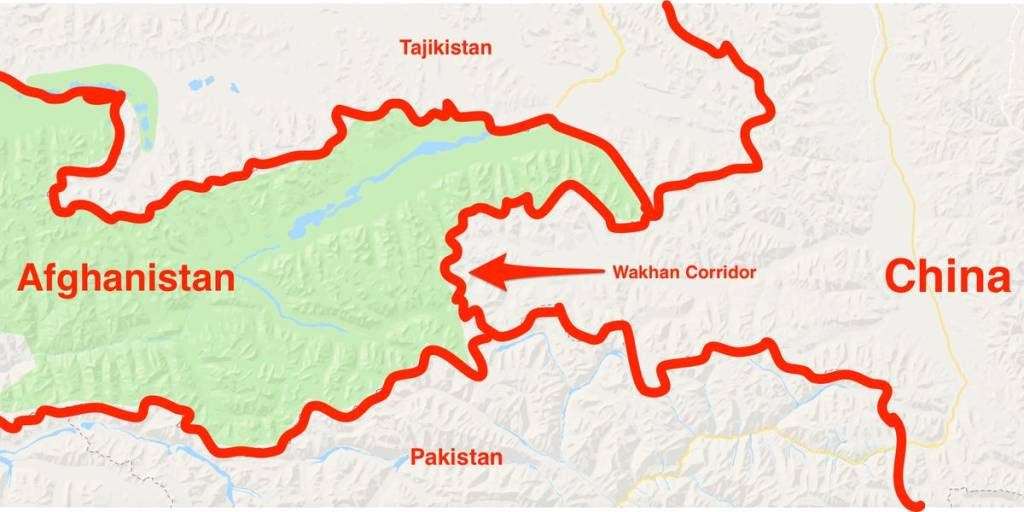

Map highlighting who controls Afghanistan. Map Source: BBC