AFGHANISTAN

LET’S be in no doubt. The UK’s latest Afghan war – the fourth since 1839 – has ended in abject failure. The shameful retreat was down to a bungled withdrawal of US forces by Joe Biden, who’s lacklustre approach leaves his leadership open to criticism of weakness and inadequacy. What extraordinary and pitiful scenes the world has witnessed in recent days: bodies falling from the sky, the Taliban cheering in Kabul and the mighty America humbled. The Taliban on the ground is operating akin to the Nazis as they go door-to-door in neighbourhoods seeking retribution against those that supported the West. There is a growing sense of unease, and rightly too, as the West awaits what might come next.

Britain scuttled out at the same time, the prime minister telling MPs on the day of Mr Biden’s announcement that there can be no military victory in Afghanistan. What a shameful assessment given all that has been sacrificed in terms of blood and treasure plundered. The world is witnessing the extent of the military and political catastrophe after twenty years of miscalculation and misadventure.

The UK is currently driven by a desire to stay close to the US. But America is a superpower, able to shrug off defeats and move on. The blow of losing Kabul is felt more deeply in Britain shorn itself of substantial global influence. And, yet, this has led the UK to take Washington’s lead in military affairs. In Afghanistan, the US judgment that a combination of special forces, local proxies and air power would wipe out domestic resistance to a military occupation was flawed. The Afghan security forces that NATO trained were exposed as a shell and collapsed at a time when it was most needed. In 20 years of relentless fighting, more than 170,000 Afghans have lost their lives. The death toll continues to rise as the barbarism of the Taliban metes out savage reprisals against local Afghans and interpreters who helped western intelligence services and the British Army in a quest for democracy and more moderate living. In June, almost 1,000 Afghans were killed in the simmering civil war. A few weeks later half the country was under Taliban control.

Western politicians prefer to tell a story of progress in Afghanistan. But that could all be unravelled now the Taliban are in control. Since 2001, the US has spent nearly $145bn (£106bn) trying to rebuild Afghanistan. By 2019, the average Afghan student received four years of schooling (twenty years ago it was just two). As prosperity was building, Afghans were known to have lived healthier and longer lives and the country is certainly wealthier than it was in 2001. But as many will soon realise the state can only function with international aid. Aid funds three-quarters of total public expenditure.

Elections were held in Afghanistan but the institutions that support democracy were not allowed to take root. One elected president, Hamid Karzai, fell out with the Americans so badly he threatened to join the Taliban himself. The other, Ashraf Ghani, fled as the Taliban advanced. Almost every other Afghan ruler in the 20th century was assassinated, lynched or deposed. A western-made “liberal democracy” has fallen into the hands of religious fanatics with close links to al-Qaeda. It must be clear by now that nations cannot be hustled at the barrel of an American gun into the postmodern age, especially when they have not been allowed to come to terms with modernity.

In Afghanistan, the battle for hearts and minds was lost long ago. Without hearts and minds, one cannot obtain intelligence, and without intelligence, the insurgents will remain undefeated.

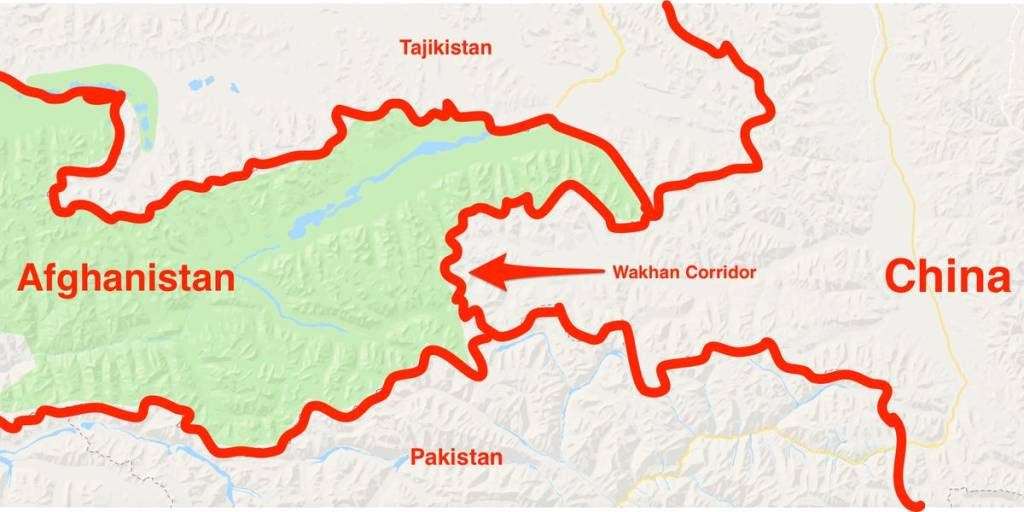

The Royal United Services Institute, a security thinktank, describes the outcome in Afghanistan as “strategically worse than the situation prior to the 9/11 attacks – a Taliban state, with terror groups already baked into it, with nowhere else to turn for major support other than Beijing”.

The collapse of the Taliban in 2001 encouraged the US to adopt a similar strategy in Iraq and Libya. After 20 years of disastrous results, British ministers should reach for a new approach. After all, relations between London and Washington have historically never been entirely unconditional. Yet, whilst the government speaks of creating new special forces regiments and naval “littoral strike groups” for international interventions, Britain needs to learn its own history. It used to station military forces around the world to maintain its empire. It should think again before doing so for someone else.