ESSAY

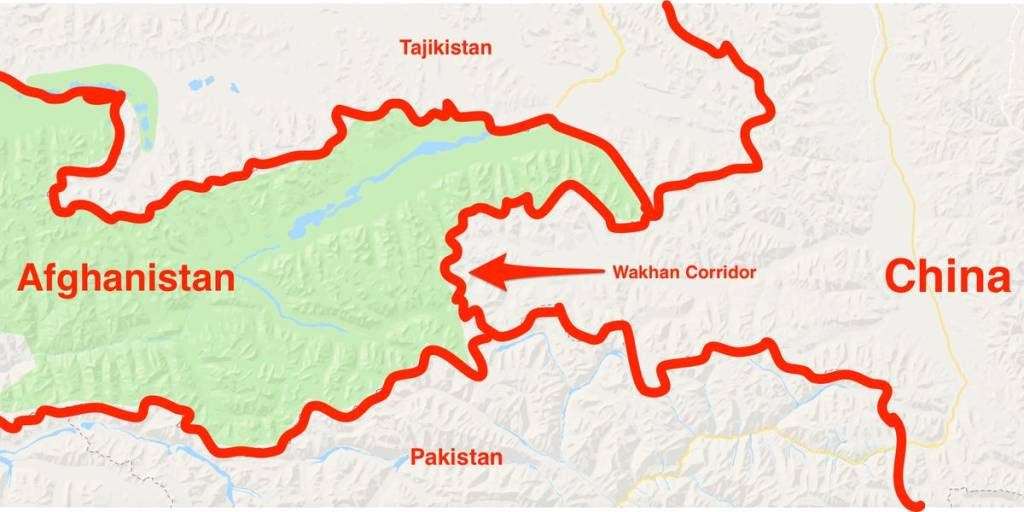

Intro: Just days after the U.S. and its Coalition partners prepare to leave Afghanistan, China is preparing to gain a direct route to the riches of the Middle East. With billions in the Chinese war chest, just where will China’s ambitions end?

THERE is a reason why Afghanistan is known as “the graveyard of empires”. Every few decades this beleaguered nation emerges from obscurity to remind an apparently invincible invader that his army is not the first to bite the bitter dust there. Afghanistan is littered with examples of invading armies sent into retreat and heavy defeat.

In 1842, the first of Britain’s four Afghan wars ended in catastrophe. Only one man survived from a force of about 4,500, plus 10,000 or so camp followers, linguistic interpreters, and local allies – and he was set free only so he could recount the scale of the defeat and the dire end of his comrades.

After ten years of brutality trying to convert Muslim Afghans into ‘modern’ communists, the once mighty Red Army found itself in humiliating defeat from Afghanistan in 1989. It would mark the beginning of the rapid fall of the Kremlin’s dominoes from Eastern Europe to Moscow itself.

Today, we see the U.S. and its coalition partners leaving Afghanistan in defeat after almost 20 years; the superpower discovering that Afghanistan’s fragmented tribal culture masks an unbreakable resilience. President Joe Biden, a recent convert to the cause of ending what he has described as a “forever war”, has set a deadline of September 11 for the last American troops to leave.

It is, of course, a highly symbolic act that marks 20 years since the 9/11 attacks by Al-Qaeda – which had its training camps in Afghanistan – that destroyed the World Trade Centre in New York.

Within two months of the invasion in October 2001 by the U.S.-led Coalition forces, Al-Qaeda’s leader, Osama bin Laden, had fled to Pakistan and the fundamentalist Taliban routed. But the mission soon lost its way, at a cost of thousands of military and civilian lives.

Now the U.S. cannot get out fast enough, abandoning its huge airbase at Bagram overnight on 2 July. Today, the situation around the capital Kabul is chaotic, its population in panic, and the Taliban is sweeping back into territory it had been forced to flee by Coalition forces.

Afghan soldiers loyal to the fragile Western-backed Kabul government are being routed. After clashes with newly strengthened Taliban units, an estimated 1,600 have fled and dispersed across the border into neighbouring Tajikistan.

Others have abandoned their weapons and uniforms to return to their homes or switched to fight with the Taliban, which is also taking territory it did not hold prior to the Coalition’s arrival.

Despite more than $2.3 trillion spent waging a war against a badly armed and underfed ragtag of rebels, the Americans leave their enemy in better shape than ever before.

But this will not deter the world’s newest superpower – China – which is waiting patiently in the wings. The Dragon of China will soon enter the fray.

In a development that should strike fear through Western capitals, Beijing scents an unrivalled opportunity to extend its influence in the region and gain strategic territorial and economic advantage that could rewrite the geopolitical map in its favour.

For President Xi Jinping’s Marxist government, Afghanistan is a prize beyond measure. It offers a portal through which Chinese military might could access the Arabian Sea, via Iran or Pakistan.

And the war-torn country could provide two other things China desperately wants: overland access to Iran and the Middle East, and a route to the Indian Ocean and on to Africa.

To reach these markets currently, Chinese goods must go the long way round, via container ships through the disputed South China Sea. But the short border Afghanistan shares with north-western China offers potential for a mega-highway, a high-speed rail link and fuel pipelines.

Beijing is confident that it can succeed where Whitehall, the Kremlin and the White House have failed over the centuries, for the simple reason that it is not interested in transforming Afghan society.

It has learned from the mistakes of the Russian communists. Chinese communists have no desire to remake Afghanistan (or anywhere else) in their own image.

Threat

Nor will its goals be achieved by brute force; President Xi has a far smarter plan. When the Kremlin occupied Afghanistan in 1979, it saw it as a steppingstone to dominating the oil-rich Middle East, but Soviet communism had little to offer compared with the wealth of modern China.

Xi prefers to use financial muscle as much as the threat of military power and, if reports that Beijing is prepared to invest $62 billion in Afghanistan are true, it is following a blueprint perfected in many countries from Malaysia to Montenegro.

Under a policy known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), vast loans are offered to cash-strapped countries for infrastructure projects. In return, China gains access to new trade routes and ports, as well as banking hefty interest payments on its investment.

If the repayments are late, the Chinese could step in to reclaim land, mineral rights, or other collateral as compensation. It is a business plan more common in the underworld of gangsters and organised crime groups: victims are lured into a “debt trap” and forced to repay, one way or the other.

In return for its largesse, China will also expect the Taliban to ignore the “genocidal” oppression of their fellow Muslims, the 12 million Uighurs in China’s Xinjiang province, which sits close to the Afghan and Pakistani borders.

The last thing Beijing wants is an anarchic scenario in which a rise in Islamic fundamentalism on its border threatens domestic security in China.

But it has seen how indifferent strict Islamic regimes in the Middle East are to Uighur rights. The oil-rich Arab monarchies will much prefer doing lucrative deals with Beijing than bothering about its treatment of fellow Muslims.

Pakistan’s Prime Minister, the former international cricketer Imran Khan, who cynics argue has reinvented himself as a born-again Muslim to cement his political power base, has spoken up about the Uighurs – but only to defend China’s handling of them.

And even before Khan came to power, Pakistan’s generals saw the Taliban as a natural ally against their number one adversary, India. China, too, is at daggers drawn with India, so it will view an anti-India Taliban regime in Kabul as a possible ally.

Uncertain days lie ahead and as the remaining American troops gather to stockade the U.S. Embassy in Kabul and protect the dwindling band of Westerners there, there are many observers who recall evacuation of the U.S. embassy in Saigon in 1975.

Similar humiliating scenes are likely in the coming weeks. Up to 1,000 U.S. troops are expected to be stationed at Kabul Airport to protect departing Western civilians.

Bleak

That will be little comfort to all those Afghans who have worked bravely with Coalition forces over more than two decades trying to improve life for their own people. Betrayed, their future is now bleak.

And, as for our pledges to women and girls – with the likely return to power in Kabul of the Taliban – they will lose those rights and freedoms that Allied intervention had brought.

China sees Afghanistan – even with the Taliban back in control – as one of the most crucial squares on the chessboard of world politics. And like a chess grandmaster, President Xi Jinping is not planning for a quick checkmate.

Historians will no doubt look back at what is happening now and see that China did indeed learn the lessons of history. Where Britain, Russia and America have failed, it may yet triumph, gaining the influence it seeks without having shed the same terrible price in blood and human sacrifice.

Appendage